The South Carolina Center for Community Literacy offers a selection of children and young adult books for the public to view and check-out (Photos by Bridget Frame)

South Carolina teachers and educators are afraid for the future of students because of the gap virtual learning has left.

The pandemic has caused concern for a “COVID-slide,” a backslide or regression in learning for young students.

Losing those crucial years for developing reading skills is the biggest concern.

“I predict what we’ll see is more of an issue with literacy in kids in third or fourth grade in the next couple of years,” said Liz Hartnett, program coordinator for the Columbia-based S.C. Center for Community Literacy. “They were the ones who were in that critical first- and second-grade year during the pandemic.”

The literacy center’s programs encourage literacy in young children. Volunteer initiatives such as Cocky’s Reading Express bring books to elementary school students and read them aloud.

These events are targeted towards young students because kindergarten through second grade is a key period for learning to read.

“That is when kids develop their basic reading skills, the ability to get meaning from text,“ Hartnett said.

When students were in quarantine and did virtual learning at home, hurdles such as the lack of Wi-Fi or computer access and a complete change in learning environment made retaining information difficult.

“Most kids need that physical, hands-on, face-to-face, visual, where you’re experiencing your teacher in real life,” said Lisa Cole, executive director of Turning Pages, an adult literacy nonprofit. “You’re experiencing your classmates in real life. They need that hands-on component.”

Oddly, the pandemic may have been a catalyst for S.C. schools to change their approaches to teaching reading.

“Everybody became a homeschool teacher,” said Valerie Byrd, coordinator at Cocky’s Reading Express and an instructor at USC.

Quickly, many parents realized their children weren’t good at reading.

That’s when experts began to rethink everything.

“The predominant philosophy around reading instruction in South Carolina for decades has been this balanced literacy approach,” said Matthew Ferguson, deputy superintendent and chief academic officer at the state Department of Education. “I think that really gets at the core of why our reading scores are where they are.”

The approach focuses on a mix of independent reading, phonics and decoding sentence structure.

It has been used since the ‘90s in schools but has recently been scrutinized for its ineffectiveness after the pandemic and virtual learning.

Reading scores had a smaller decrease after the pandemic than expected. But that isn’t as great as it sounds, as students already had a large lapse in reading skills.

Changing the teaching method in schools may help recover from the virtual learning gap.

“They’ve focused on that through really attempting to provide professional development and high quality instructional materials around scientifically based practices and teaching reading,” Ferguson said.

There’s hope that this Covid slide won’t last forever and that these changes will make a difference.

“I think when we do that for students, we are going to see their learning really accelerate,” Ferguson said.

But getting students engaged may be the key to changing literacy.

“Having books in classrooms and libraries that kids want to read, I think can have a positive impact on that reading,” Byrd said.

A variety of books are provided by donations from publishers, allowing the literacy center to provide new books to elementary school students.

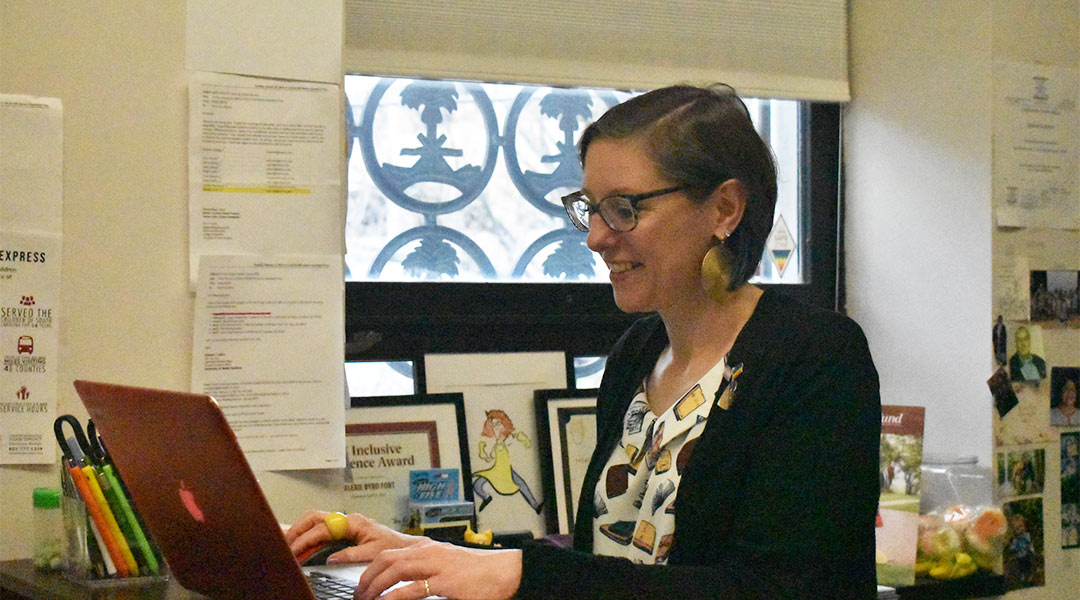

Valerie Byrd runs Cocky’s Reading Express, a volunteer project at the literacy center that brings books – and Cocky – to elementary school students across the Midlands.

The literacy center doesn’t just have picture books. It also has young adult novels and chapter books for older kids

Liz Hartnett is the program coordinator for the literacy center.