Many UofSC students wear masks while on campus which officials say is one of the keys to a low COVID-19 case count. Photo credit: Christopher Lorensen

It’s been nearly three months and 2,500 coronavirus cases since the University of South Carolina started testing to determine if the school could remain open throughout the pandemic.

Nationally recognized for a high total case count at the start of the semester, UofSC is now reporting only 22 cases because of early planning and a coordinated effort among faculty, officials said.

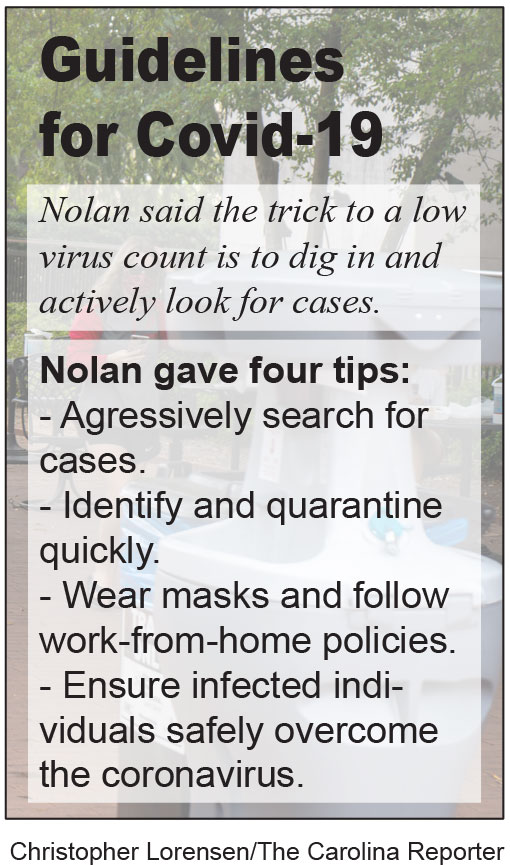

“I think that the success stories come from the places that really dig in and look for cases aggressively instead of just waiting for passive surveillance,” Melissa Nolan, assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics in the Arnold School of Public Health, said. “We started thinking about this (COVID-19) back in March.”

Although the current case count is low, UofSC reached a peak of about 1,500 cases in early September before the university started to see a decline. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released research results that show weekly COVID-19 cases increased by 55% among 18 to 22 year olds during the start of the fall semester.

“We had a really high number and we anticipated that. When we did the modeling, we knew we were gonna have a certain number but there was a cut off,” Nolan said. “Fortunately we never got there.”

The CDC states in the report that although this demographic is at a lower risk for severe symptoms or death, they can still spread the disease to those at high risk. The report encourages universities to take steps to reduce the spread of COVID-19 because an increase in cases in one community risks further spread into neighboring communities.

Nolan said maintaining a low case count is based on four strategies: aggressively searching for cases, identifying and quarantining those cases quickly, ensuring individuals safely overcome the virus if infected and wearing masks along with work-from-home policies.

“We were fortunate that people wanted to get tested,” Nolan said. “We were also able to effectively contact trace for the first 24 to 48 hours.”

However, large amounts of volunteer testing hasn’t lasted. While there were long lines at the testing site to start, students are now being incentivized via free T-shirts and are being chosen at random to be tested. Even if chosen randomly, the test is still optional.

At the beginning of the semester, Nolan says most people getting tested were likely doing so for their own safety. The incentives are to encourage a shift in public thought on how students perceive the importance of tests.

“So now it’s shifting away from ‘Well, I need to get tested for my own concern,’” Nolan said. “It’s more ‘I need to get tested if I’m asymptomatically infected.’ I would know that status and I could protect those that I love.”

Getting tested and performing contact tracing is only half of the strategies needed to reduce the spread of the virus. Nolan said from an idealistic public health standpoint, it’s always good to have a continuation of policies among all communities.

Social distancing violations such as pool parties and large gatherings in Greek housing were accused for the rising case counts at UofSC early in the semester. Following reprimands from school officials, cases started to subside.

The university fell out of media attention until a recent, post-game football party involving over 2,000 people. The majority were not wearing masks or social distancing as they celebrated UofSC’s win over Auburn.

It is too early to tell if the gathering will have any negative effects on the university’s low case numbers or local communities, but UofSC President Bob Caslen sent a letter to students shaming those who attended the party and reminding others to be models for their peers and the Columbia community.

“To those students who participated in the party on Saturday (or any other large social gathering), I encourage you to think beyond yourselves and to loosen your grip on a perceived entitlement to doing as you please without considering how your actions could harm others,” Caslen wrote in the letter. “Our relationship with the campus and greater communities is significantly impacted by our actions.”

Some officials warn of becoming complacent with the virus. Governor Henry McMaster said to beware of testing fatigue.

“Right now the question is not so much the availability of tests but the people’s willingness to go get one,” McMaster said. “We know now that the younger people can get it (coronavirus) but not know it and still spread it.”

Test fatigue is thought by some to be contributing to the low active cases at UofSC, but wastewater data from Sean Norman, director of the Molecular Microbial Ecology Lab, mimics the data from direct testing.

“I have people ask me all the time here on campus but also out in the community ‘What do your numbers look like? Because we don’t necessarily trust the numbers because of testing fatigue and turn around time and everything,’” Norman said. “Well our numbers are backing up what you see in other places.”

Norman has partnered with the CDC and the state Department of Health and Environmental Controls since March to monitor eight wastewater sites throughout South Carolina along with one in Waco, Texas, and the Bay Area in California. He and his graduate students track trends in COVID-19 based on the amount of the virus per liter of wastewater.

“We got to see very similar trends to individual case counts that’s put out by DHEC. As a matter of fact, our curves almost overlaid,” Norman said. “We saw things like what they now consider the Memorial Day bump.”

Norman’s data also shows a correlation between face masks and viral load. He said there was a continuous increase in viral load and coronavirus cases until about early July when mandatory face mask ordinances were established.

“About 1 to 2 weeks after that we saw an incredible decrease in the abundance and while we can’t say face mask ordinances caused that, there was certainly a correlation,” Norman said.

Norman says that most of the time he will see trends up to a week before DHEC does via individual testing because of his ability to see the viral load of all people in a community.

“The important thing in sewage is it’s not dependent on a person feeling symptoms and going to get tested,” Norman said. “Independent of testing fatigue, we’re going to be able to sample roughly the same amount all the time.”

While the use of wastewater testing is becoming more reliable and efficient, Norman said it should not be used as a replacement for individual testing but as complementary data.

“We’re at a community level. So if an individual wants to know if they are carrying the virus or not they actually have to go and get an individual level test,” Norman said. “There is no way to get around that.”

Melissa Nolan is an assistant professor at the epidemiology and biostatistics department in the Arnold School of Public Health. She says that community, policies and an aggressive plan are key in staying open during the pandemic. Photo credit: UofSC.

UofSC professor Sean Norman analyzes wastewater for signs of COVID-19 and often will see data before DHEC does from individual testing. Photo credit: UofSC.

Norman and his graduate students don safety gear in preparation for testing wastewater in South Carolina. Photo credit: UofSC.