The Supreme Court of South Carolina building is home to the state’s Access to Justice Commission. (Photo by Emmy Ribero/Carolina News and Reporter)

Researchers at USC have published a study on orders of protection taking a first look into what happened to victims of domestic violence and the gaps found in how South Carolina courts handled them.

The report found various ways domestic violence victims could be better protected by the state’s legal system.

The research was pioneered by Lisa Martin, a professor at the Joseph F. Rice School of Law, and Dr. Suzanne Swan of USC’s departments of women’s and gender studies and psychology. They presented their findings at the Joseph F. Rice School of Law on April 8.

The project took a census-based approach to finding patterns in domestic violence cases on a local and state level, as opposed to collecting a sample. A majority of order of protection cases from one calendar year were collected from every county, in part due to the help of USC undergraduate law students who traveled to find, redact, and analyze the data, Martin said.

Orders of protection, similar to restraining orders, are a civil legal remedy under the Protection From Domestic Abuse Act in South Carolina. The option is available in most state family courts, and is used to protect victims against domestic violence. The research team collected 3,451 order of protection case files from the time span of Jan. 1, 2019, to Dec. 31, 2019, from 45 of the state’s 46 family courts.

“I really just can’t overstate the importance of data when we’re talking about access to justice,” Martin said. “Even though information that we get from advocates on the ground is extremely compelling, it is also extremely easy to dismiss without data to back it up … and we found this with a lot of access to justice issues. Gaps in data inhibit problem-solving, they inhibit innovation.”

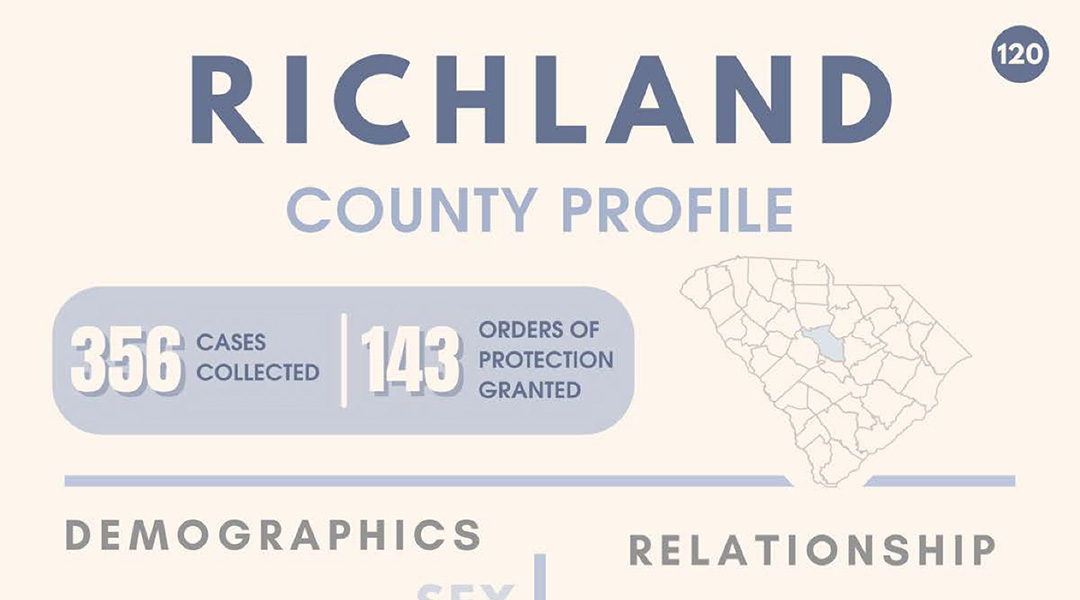

Richland County saw 0.89 orders of protection filed per 1,000 residents in 2019, falling in the 75th percentile of all state counties.

Based on their collected research, the team proposed several potential remedies to the problems found in the state’s legal system.

Orders of Protection are filed by the victims, known as “petitioners,” when they have a familial relationship with their “respondent” and have experienced qualifying conduct.

These two terms – familial relationship and qualifying conduct – are areas of the legal process in which the researchers found “glaring” gaps, Martin said, that put restrictions on the number of people who can seek protection from their abusers.

In South Carolina, the petitioner must have been married or formerly married to their respondent and/or shared a residence with them at some point to qualify for an order. Martin said it was clear to them who was left out from receiving protection. She recommended that relationships qualifying for protection should be expanded to include dating partners who have never shared a residence.

South Carolina is one of only three states that doesn’t offer protection to intimate partners not sharing a residence, despite State Law Enforcement Division data showing that these intimate partners experience high rates of violence, Martin said.

Two out of three petitioners during the period studied described physical abuse, and half reported threats to kill or harm them, according to the report. Examples of physical abuse in the files included strangulation and being threatened with a weapon, both of which make the victim more likely to be murdered by their abuser. These types of abuse – physical violence and threats – are required by law to be reported to qualify for relief. But there were multiple other types of conduct reported that are indicative of future violence and should also qualify, including stalking and harassment, Martin said.

Eighty-one percent of the petitioners studied, most of whom were female, reported more than one type of abuse. One in four reported being stalked. Stalking often occurs before serious violence and intimate partner homicide, Swan said. Three in four women who were murdered by their partners reported being stalked first.

The timing aspect of these cases poses problems as well, Martin said. There are two elements of this that Martin said are significant in their research: the time it takes for a hearing to be granted and the duration of the order itself.

Data showed that both of these categories varied greatly by county. In some counties, most petitioners are protected within five days. In others, it took weeks.

Timing is incredibly important in these situations, Martin said, because the period of separation between a petitioner and respondent is “the most dangerous time in an abusive relationship.”

South Carolina is the only state that doesn’t offer temporary Orders of Protection at the time a petition is filed, which would protect the victim between the start of separation from their abuser to the hearing of the case. A hearing must be scheduled within 15 days of filing unless an emergency hearing within 24 hours is granted by the court.

The lack of temporary orders leaves partners vulnerable at the most dangerous time in the relationship, Martin said. The gap also pressures courts to move at “warp speed,” sometimes forcing petitioners to return to court multiple times before the respondent is served. The respondent must also be notified that a case has been filed against them before it can move forward in court.

Martin said protections should be expanded to establish temporary orders of protection and empower family courts to issue them to ensure the protection of victims.

“Creating temporary orders will not only allow the process to move at a more reasonable pace for everyone involved, but will create a zone of safety that is critically needed for petitioners while their cases remain pending,” Martin said.

Orders of protection are typically granted for a duration between six months and one year, at the court’s discretion. The lengths of time for when petitioners are protected also varied by county. In some, most were protected for a full year, where in others it was common for victims to only be granted half that time.

Even if a victim does qualify, only 46% of the studied cases resulted in a granted order of protection. Other cases are resolved in a variety of ways, such as dismissal by party consent, petitioners failing to appear in court and/or denials.

Of 356 orders of protection files in Richland County collected by researchers from 2019, 143 were granted.

The researchers also found that lawyer representation is rare in Order of Protection cases statewide. In three of four studied cases, neither party was represented by a lawyer. The report contains data on what percentage of each party was represented in each county, as well as how long it took for an order to be granted after a request was filed.

Out of those 356 files collected from Richland County cases, neither the petitioners nor respondents had legal representation in 62% of them. Fourteen days was the average time it took for an order of protection to become effective after filing. In 69.2% of the collected cases, petitioners received one calendar year of protection. The majority of the rest granted six months.

The researchers also recommended increasing the accessibility of court data to assist future research on how orders of protection and other remedies operate in practice, so they can learn how to better improve the laws to protect them and other people.

Also in attendance to comment on the study was Sara Barber, the executive director of South Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault.

Barber emphasized three major takeaways from the research. One is that it’s important to understand that these cases involve real victims who are scared, actively in danger, and are putting themselves at risk by coming forward to seek an order of protection.

Every order of protection filing has a narrative section describing the abuse experienced by the petitioner. Many of these sections included quotes from abusers directed toward their victim, for example, “He said, ‘You belong to me until the day you die and you’re not dead, yet!’”

Barber pointed out also that “the gaps are enormous” in the legal and legislative system, and efforts to remedy them are slow.

She said Senate Bill 143 would expand the qualifying relationships for orders of protection, but is stalled in the legislature after passing the Senate Judiciary Committee and the full Senate last year. She said she doubts the bill will pass in this legislative session. Regarding the lack of temporary orders, House Bill 3867 would remedy that issue, but is also stalled in the House right now.

“It’s probably not going to make it, and we’ll have to start again,” Barber said of both bills and the end of the two-year session. “And we will start again, because we’re advocates, and we keep on going.”

Her third takeaway emphasized that advocates across the state are continuously and actively seeking ways to provide support. As an effort for said advocacy, Barber said, SCCADVASA started a legal program in 2018 to remedy the lack of representation in these cases.

Remarks were given at the presentation by Joseph F. Rice School of Law Dean William C. Hubbard and S.C. Supreme Court Justice John C. Few, who works with the S.C. Access to Justice Commission.

Few said reports such as these are “a great privilege” to the Access to Justice Commission.

“Pretty much everybody in this room lives in … a bubble when it comes to what’s really going on out there in our society,” Few said. “Understanding what is actually going on is critical to knowing how to take the first step … and subsequent steps to try to help people deal with the problem.”

The study is the first to be completed in a series that will later delve into restraining orders and other access to justice issues, Martin said.

USC researchers Dr. Suzanne Swan, left, and Lisa Martin presented their research on Orders of Protection in South Carolina at the Joseph F. Rice School of Law. (Photo by Riley Edenbeck/Carolina News and Reporter)

A snippet of the research team’s profile of the data collected from Richland County for its report (Photo courtesy of USC and researchers Dr. Suzanne Swan and Lisa Martin/Carolina News and Reporter)