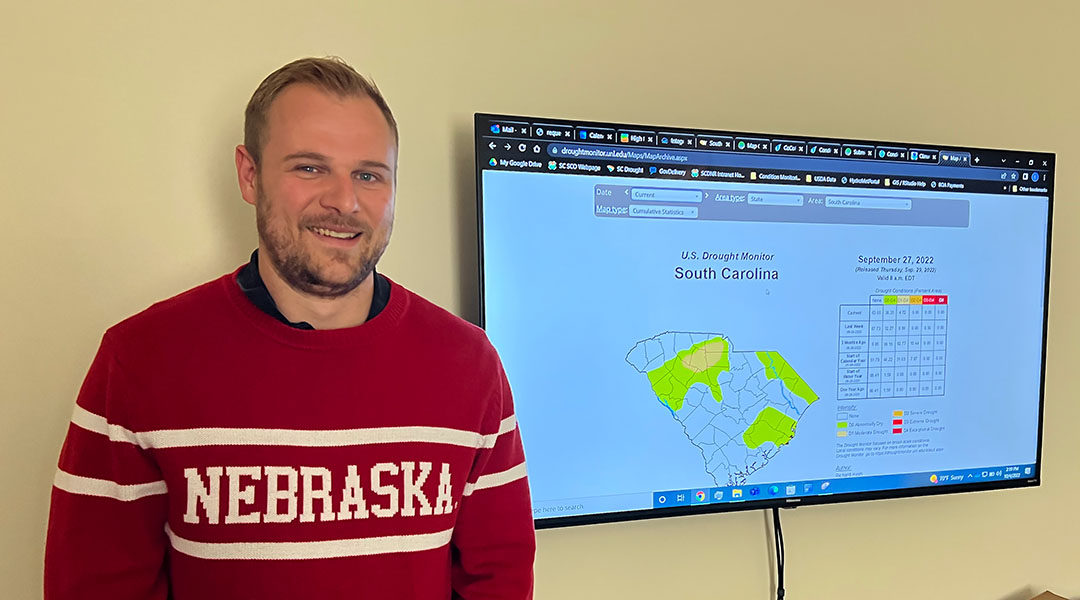

Elliot Wickham is a water resources climatologist at the S.C. Department of Natural Resources. (Photos by Danielle Wallace)

As tropical storm Ian came and left the Midlands last weekend, many area residents feared heavy rain and flooding.

Yet for those impacted by the state’s ongoing drought, the storm was a relief from a period of heavy dryness. But it wasn’t a complete fix. With the third La Niña winter in a row approaching — a rare occurrence called the “triple dip” — South Carolina is leaving an overall dry summer and entering a warm, dry winter. That’s a lot of dryness.

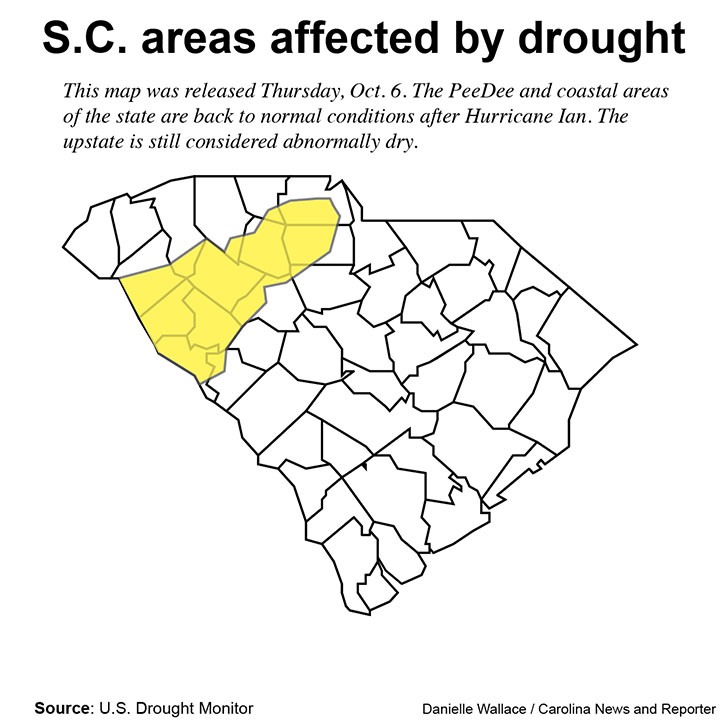

Although the average Columbia resident doesn’t see many effects from the drought, farmers across South Carolina have been dealing with it for months. The tropical storm helped them a bit — it gave some rain to the coastal and PeeDee regions. But areas such as the upstate are still drier than normal.

Jason Roland owns and runs a small farm in Lexington. He said Ian helped his farm because the storm hovered instead of moving quickly through the state. That means the rain had time to soak into his soil “perfectly.”

“Whenever you have those downpours, it’s one of those things you have to watch out for as a farmer,” Roland said. “It all gets washed away. It does no good … it’s like you would’ve rather not had the rain than to have had it.”

A drought can be difficult to identify sometimes. An area can experience unusual dryness, yet not technically be classified as having a drought.

“Drought is a very messy and complicated natural hazard,” said Elliot Wickham, a water resources climatologist at the S.C. Department of Natural Resources. “It’s the one natural hazard that does not have a universal definition.”

After Ian, Wickham said some areas that were considered abnormally dry before the storm but received ample rainfall are projected to improve drought-wise.

“Pretty much everything south of the fall line (in Columbia) — like the coastal plain and all that — is going to be normal conditions,” Wickham said.

Wickham said drought is divided into the following categories: abnormally dry, moderate, severe, extreme and exceptional. He said before the hurricane, 31.6% of the state was abnormally dry, and 4.72% was in a moderate drought.

A drought takes time to develop, Wickham said. And its effects take time to be seen.

“It’s a slow-moving hazard,” Wickham said. “The amount of water that you would lose in a week, you could easily gain that back with a big storm. It could take weeks, if not months, to really dry yourself out.”

Roland said he doesn’t believe South Carolina is in a “drought,” for lack of a better term.

“I think the South is just kind of … in a new weather pattern,” Roland said. “I don’t know what the word would be for that, but it’s just how the world is now.”

Before Ian, Roland had not seen rain for 34 days. Aside from some rain and flooding this past July in Columbia, he said the early summer was extremely dry.

Then, “in July, it didn’t quit raining — it rained like every other day,” Roland said. “And then that’s not good either, because you end up with so much humidity.”

Drought effects can go beyond precipitation, though. In terms of wildfires, the tropical storm didn’t change much in areas that got little rain.

“Now, at least for most of the state, I think we’re in a lot better shape looking at potential for a fall fire season,” said Darryl Jones, the fire chief at the S.C. Forestry Commission. “(But) up in the mountains, Oconee County and some of Pickens, really got almost no rain out of this.”

Wickham said there has not been a bad statewide drought since about 2007 through 2009. So South Carolina is due for one — he just doesn’t know when.

“(You) can’t manage what you don’t monitor,” Wickham said. “So, if we’re monitoring this, and we know we’re on this every week … you at least kind of know the progression and know (if) you need to take action.”

The only thing that could change conditions is if another hurricane strikes. Roland, meanwhile, has adapted to the drier conditions.

“It’s the weather as I know it,” he said.

Jason Roland owns and runs a small farm in Lexington, South Carolina, and is dealing with effects of the ongoing drought.

This map’s data from the U.S. Drought Monitor shows South Carolina’s drought conditions as of Thursday, Sept. 29. The yellow areas represent abnormally dry conditions, and the orange area represents moderate drought.

This map’s data from the U.S. Drought Monitor shows South Carolina’s improved drought conditions as of Thursday, Oct. 6.

The S.C. State Climatology Office is a part of the S.C. Department of Natural Resources on Assembly Street.