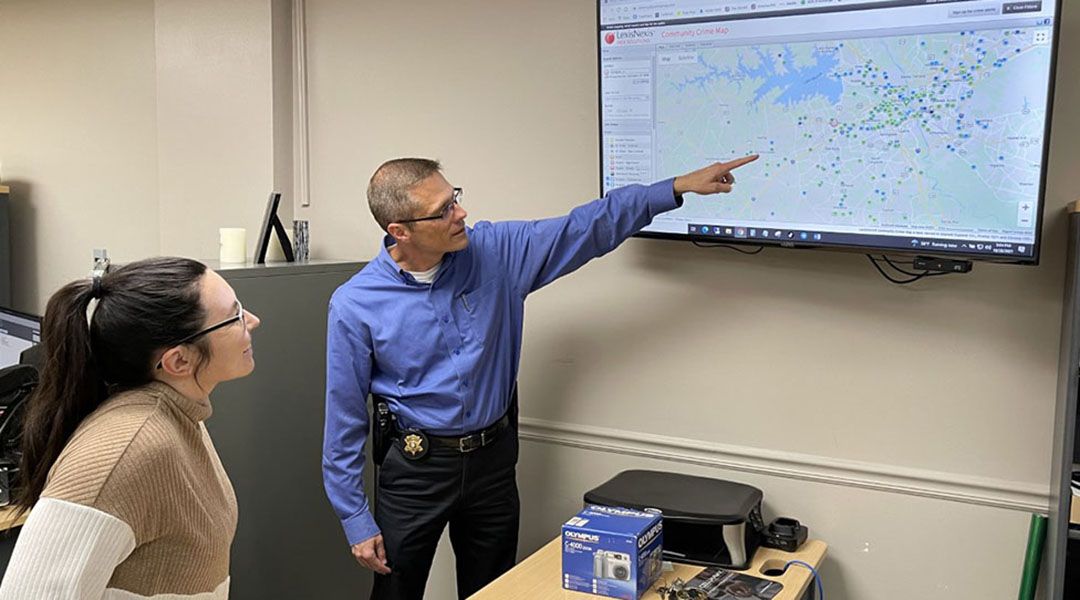

Capt. Luke Fossum of the Lexington County Sheriff’s Department analyzes a public crime map with one of the department’s two full-time crime analysts. The analysts look at county data daily to see where crime is concentrated. Photos by Emma Dooling

North Columbia’s Belmont community resolves any crime issues quickly, but that wasn’t the case when Richard Hammond moved back into the neighborhood 20 years ago.

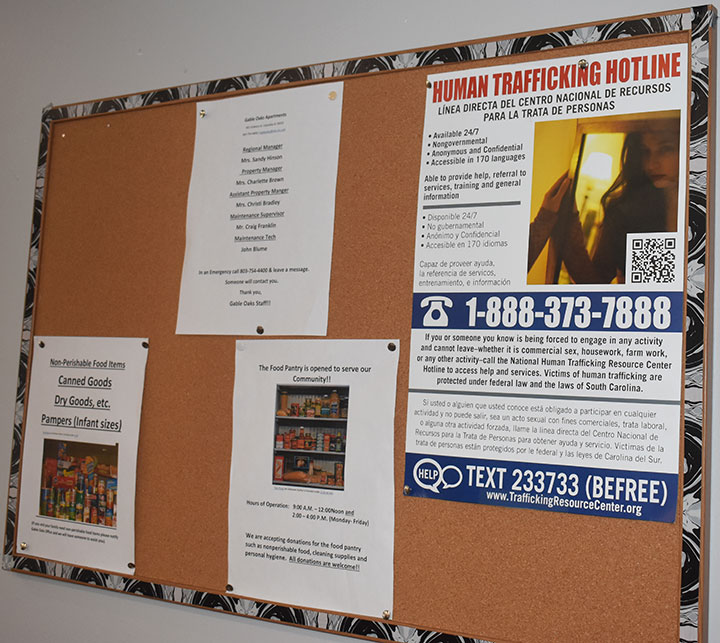

When he became president of the community association eight years later, Hammond set out to reopen communication with the City of Columbia Police Department’s North Region, which patrols the neighborhood, to decrease crime rates and increase trust in the police among residents. Belmont, a neighborhood with a large Black population off North Main Street, is home to approximately 2,500 people in single-family residences and the Gable Oaks Apartments.

Today, when a crime occurs in the Belmont community, Hammond and CPD’s North Region are usually able to address it before it becomes a hotspot.

“Not much is going on in this neighborhood, and we pride ourselves on that,” Hammond, 51, said.

Decreased crime and improved police and community relationships in the Belmont community are partially the result of a policing strategy called crime mapping.

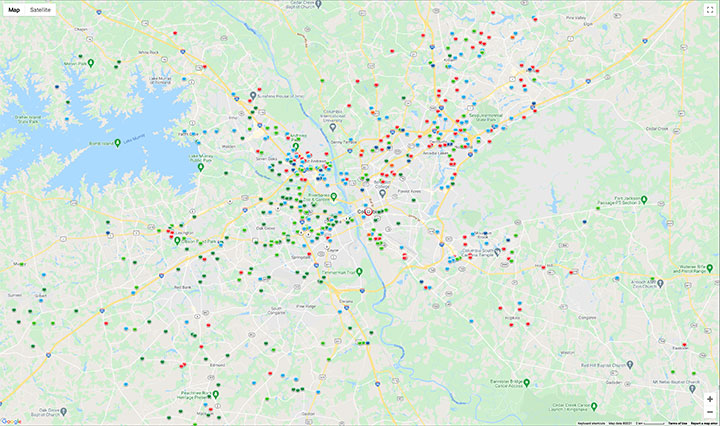

Crime mapping has been a technological movement in police departments across the country for over 30 years now, said Cory Schnell, an assistant professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of South Carolina. This mapping, which is in use by the majority of police departments today, helps structure directed police patrols, or patrols sent to specific areas of a department’s jurisdiction, to help the communities most in need.

“The idea of patrol is like the backbone of modern policing,” Schnell said. “Patrol and how you allocate your limited resources is one of the most important things cops do.”

Handling the hotspots

Canon Fulmer is a lead analyst and investigator in CPD’s Crime Gun Intel Unit. Fulmer helps determine where gun crimes are concentrated in Columbia at any given time.

“Crime is not evenly distributed across the city geographically,” Fulmer said. “It cools and collects in certain areas.”

And most places within these areas, Fulmer said, do not experience gun violence. In the last six years, Fulmer estimates about 38% of person-hit shootings (when someone is shot and injured) have occurred in only 2% of the reporting areas in Columbia. These numbers remain relatively consistent over time.

“It’s a very small subset of the places in that community — like, we’re talking about specific block faces — that have a chronic problem with gun violence,” Fulmer said.

These areas are known to law enforcement as microplaces, or hotspots. Hotspots can vary from a single residence to miles of land and tend to experience a single type of crime. Once a police department identifies a hotspot, it sends directed patrols to try to prevent the crime from occurring again and to identify previous offenders.

While hotspots usually come and go as they are identified and addressed, specific locations remain hotspots for prolonged periods of time. Lt. Jeffrey Brink, who works in the North Region Patrol Bureau at CPD, said these locations are called generational hotspots and are consistently patrolled.

Directing patrols to hotspots has proven to work. CPD has seen this progress in tracking gun crimes in particular.

“The maps have shown us through person-hit shootings and just gun violence in general that our focal points are in the right spot because we are traditionally in those areas on a regular basis for general calls for service and directed patrols, and those are where the heat maps are showing most of the crime is occurring,” Brink said.

Daily, focused crime mapping also helps prevent over policing and profiling in neighborhoods because of departments’ focus on the specific streets, blocks and residences instead of entire communities.

“That goes a long way towards enhancing those community relationships and making sure that we’re policing with a scalpel and not a hammer,” Fulmer said.

Bridging the gap

Building relationships with community members, officers from the Richland County Sheriff’s Department, the Lexington County Sheriff’s Department and CPD each said, largely contributes to the success of crime mapping, and vice versa. When a hotspot arises, law enforcement is able to get in touch with residents in that area quickly to warn them of the trend and gather information. Alternatively, residents have begun to feel more comfortable calling police when a crime occurs in their neighborhood.

“You don’t build a relationship with somebody during a crisis,” Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott said. “You’ve got to have that foundation a long time before that crisis ever starts.”

The three departments regularly send officers to community meetings and events in order to connect with residents.

Serve & Connect, a nonprofit that works to improve public safety in communities across the state, holds at least two large community events every month, most of which police officers attend. The events are either requested specifically by neighborhoods or planned based on hotspots found in the area.

Omari Fox, the lead community organizer for Serve & Connect, said most residents, even those traditionally antagonistic to police presence, want police to patrol their neighborhoods and have gradually become more comfortable at community events. What the public needs the most, Fox said, is confidence in the ability to continue the conversation outside of these events, where residents can interact with the police without fear of retaliation from neighbors. Fox calls those “safe zones.”

“We’re at a tipping point where the community project is going to be the thing that sustains or amplifies the impact of the conversation,” Fox said.

Brink said developing these connections also helps CPD gain back the trust from residents that it may have lost in past encounters and increases the likelihood that they will call the police when future crimes occur.

“As long as people feel comfortable being around law enforcement and being at events sponsored or assisted by law enforcement, it’ll lessen the stigma in the neighborhoods of, ‘Oh, don’t mess with the police, they’re just trying to arrest people,’” Brink said.

Hammond, a truck driver, said the Belmont community has come a long way since he moved back and is now in weekly, if not daily, communication with CPD’s North Region officers.

“It takes both sides, though, to fix it,” Hammond said. “It’s been broken for a while in Black communities.”

The Richland County Sheriff’s Department, the Lexington County Sheriff’s Department and the City of Columbia Police Department all contribute crime data from their records management systems to this community crime map available to the public here.

Richard Hammond is the president of the Belmont community, which covers over two miles of single-family residences and the Gable Oaks Apartments in North Columbia.

Hammond said the community also works to prevent crime through education, including regular programs and services about crime and public safety.

Richland County Sheriff Leon Lott receives weekly reports on crime data in the county and what the department has already done to address any hotspots. “It’s not so much the system as it is the people who are working it. A robot could sit there and hit the keyboard, but a real person understands what that means,” Lott said.

CPD North Region Community Response Team Officer A. Maurer plays basketball with a young boy at a community engagement event. Photo courtesy of the City of Columbia Police Department

The Belmont community has a monthly neighborhood meeting at New Jerusalem Interdenominational Church, where an officer from CPD’s North Region team usually updates residents on the community’s most recent crime statistics.