Fourth in a four-part series

Fewer juveniles are entering the South Carolina detention system and these declining numbers may shine a better light on the state’s Department of Juvenile Justice, a system that has come under scrutiny for decades.

Following last year’s investigation into the deaths of two juvenile inmates, the S.C. DJJ has come under more examination after allegations that the department failed to report inmate deaths.

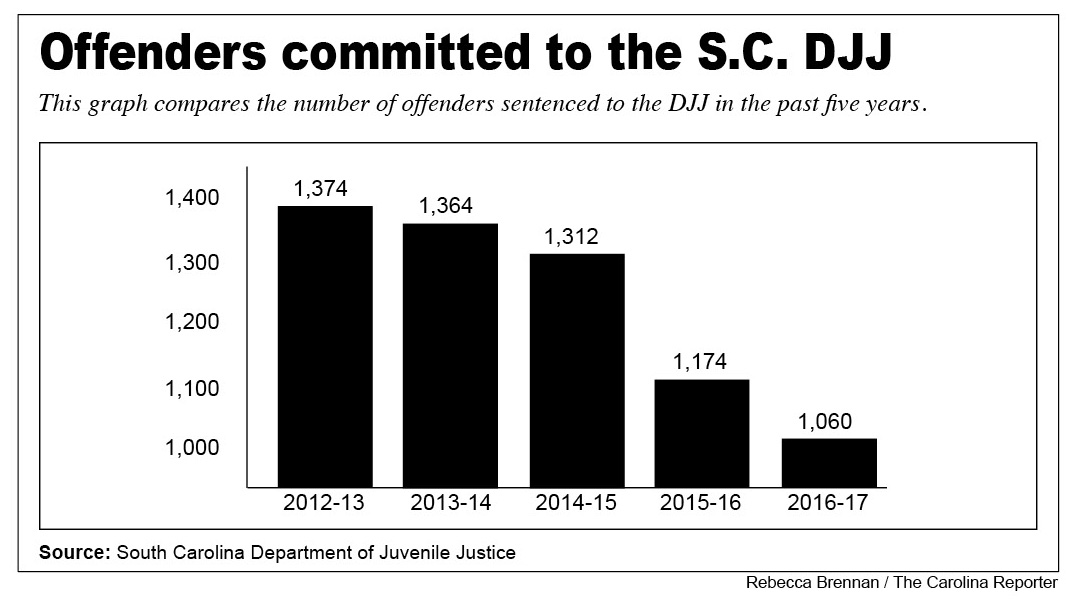

The number of juveniles offenders in South Carolina dropped to 1,060 in fiscal year 2016-2017 from 1,374 five years earlier, in fiscal year 2012-2013. According to the DJJ, violent and serious crimes in South Carolina’s juvenile system have decreased by 52%, after 2010 state Senate legislation that reduced sentencing for non-violent crimes.

Despite the lower numbers of those serving time, former juvenile probation officer Zakiya Esper believes there is more to be done for these young kids.

Esper is the founder and executive director of Sowing Seeds into the Midlands, a program that focuses on interrupting the school-to-prison pipeline through advocacy, education, and directed services. Esper doesn’t see the need to put children in jail. Instead, she believes that there are other ways to support them while promoting life skills like conflict resolution.

“I was frustrated because we have this kid who made a poor choice, which is what kids do,” said Esper. “And now we’re sending him off to boot camp or a group home and then ultimately they end up on Broad River behind the fence.”

“Behind the fence” is a phrase Esper and others familiar with the Department of Corrections use to refer to the adult prison complex off Broad River Road. Her mission with Sowing Seeds is to keep participants in her program from returning to juvenile detention centers or heading to adult prison.

“If what you want to do is punish people, cool. We’re doing that,” said Esper. “But if what you want to do is help people show up differently, what gets us there?” She organizes workshop and community service programs.

Esper is not the only one advocating for young adults to stay out of the system. Columbia Police Deputy Chief Melron Kelly says programs like Sowing Seeds are beneficial, though many young people don’t know about the opportunity.

Kelly is a native of Columbia and has devoted his time as an officer creating policies that will minimize incarceration and help people adjust to society.

“I know that sounds crazy because my job is putting people in jail, but I think that works,” said Kelly.

In his experience, Kelly has found that by giving young people a chance and the tools to succeed, it isn’t likely you will see them in trouble again.

Early in his career, Kelly lived, shopped and spent time in the same area where he policed, working with young adults daily and growing close enough to call them “his kids.” Looking back on his own youth, he said he could have taken a different path if not for caring adults in his life.

“As much as you pour into them, unfortunately sometimes the streets are going to get them,” said Kelly. “I wish I could save every last one of them.”

For those that end up in juvenile detention facilities, each program and training option serves a common goal – to keep them from coming back.

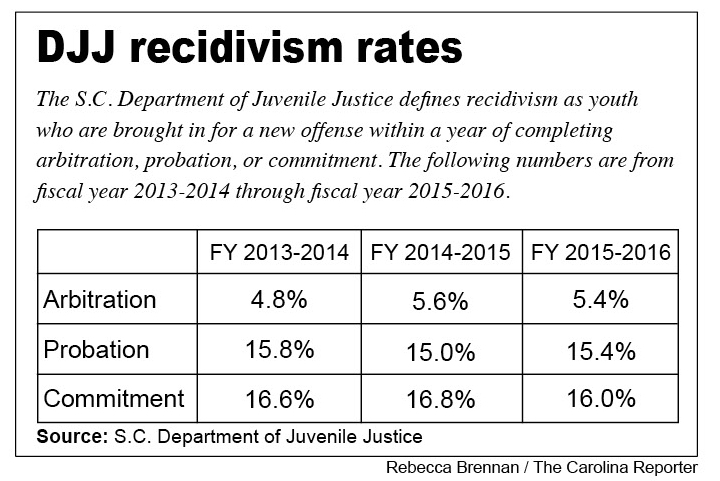

Jarid Munsch, the public information officer at the S.C. Department of Juvenile Justice, believes a combination of equipping and preparing juveniles with skills before their ‘re-entry’ is a vital part of their success after leaving DJJ. Although recidivism rates at the DJJ have remained fairly constant over the last few years, these programs are looking to lower the number of juvenile inmates that cycle back through the system.

A recently developed program at the DJJ is bridging the gap between detention centers and home life for those children in long-term commitment at Broad River. The Genesis: A New Beginning program, named after the first book in the Bible, aims to give juveniles a new outlook and skills essential to their success outside of the fence.

“The program focuses more about the soft skills and being able to think independently and critically and responsibly and make good choices,” Munsch said. “That’s the kind of stuff that isn’t necessarily found on a resume, just things that are building good character traits.”

Through this program and others like the Job Readiness training offered at the DJJ, youth offenders are given the opportunities to better themselves before returning to their communities.

Sharon Brunson, volunteer coordinator at the DJJ, has been a part of the department for nearly two decades and now plays an integral part in this eight-month-old program.

Without the skills and resources juveniles receive in these programs, they re-enter the same environment that they left with little to no change, and the DJJ is just asking for repeat offenders to transition back into the system.

“One of the best things about this program is we are able to follow up with our young men and women once they are transitioned back home,” said Brunson.