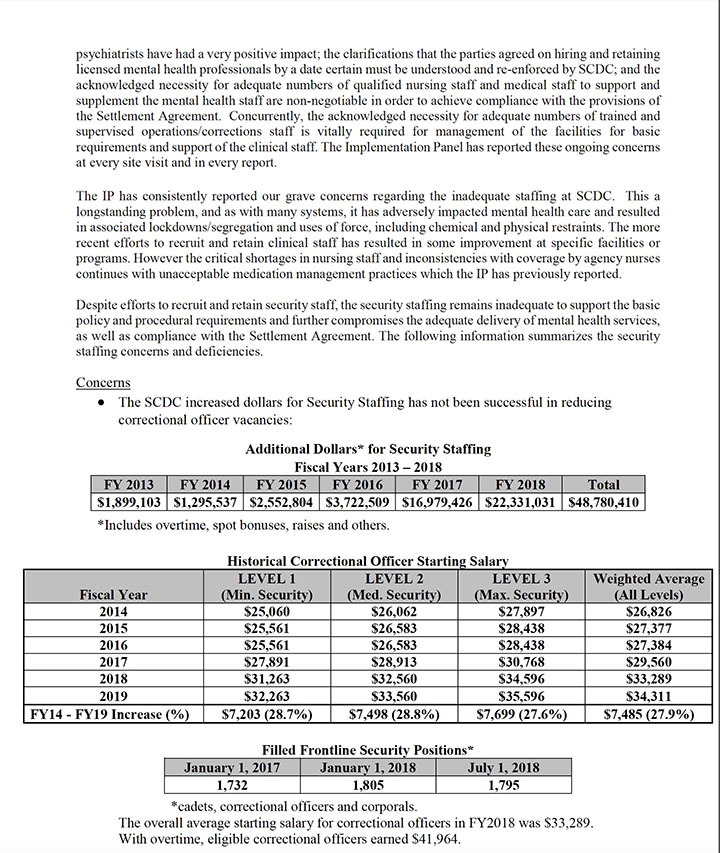

Camille Griffin Graham Correctional Facility is a Level 3 high security state prison for female inmates in Columbia. The facility off Broad River Road houses up to 489 inmates.

Part three of a four-part series.

For visitors to South Carolina state prisons, the breaking of the link to the outside world is deliberate and swift. Armored double doors slam shut, pockets are emptied, shoes are removed for searching, cellphones are confiscated and ID’s are held as collateral.

Cpl. Moldavia Canada goes through this process at Camille Griffin Graham Correctional Institution multiple times each week.

A Level 3 high security state prison off Broad River Road, Graham is one of the state’s two prisons for females, housing inmates with violent criminal histories, behavioral problems, offenders with special needs and females on death row. Canada, 32, has spent the last eight years of her life as a contraband officer here.

“It really doesn’t feel that long,” she said. “It just shot past. My best friend was working in corrections and I just thought ‘oh, that’s something different’ and that’s why I applied.”

Now, that “something different” has become Canada’s day-to-day.

After work, Canada likes to spend time with her four-year-old daughter. At work, though, she must shift gears to become the backbone that she needs to be for the facility’s inmates. It’s a transition.

“When I’m at work I have to be a leader that they need to listen to, I have to be the officer,” Canada said. “I have to be the one that’s rehabilitating. I’m not going to say the enforcer, because that’s not a good word, but I’m the person that’s got to watch all of the rules and regulations.

“If I’m going home, now I’m a mother.”

She acts in a motherly but stern way to the inmates, many of whom are mothers themselves. She oversees prisoners as their children come to visit on weekends, addresses inmates — some of them repeat offenders who she has seen for years — by name and corrects uniform dress-code violations in a familiar-yet-firm manner.

Officially, her job is to scan the one-and two-bunk cells for contraband, confiscating bootlegged items on the institution’s prohibited list such as homemade banners and Mary Kay makeup. But, personally, Canada views her occupation as something more.

“All of them here are not lifers, so they are able to go back to society,” Canada said. “I tell them ‘you made a mistake, now it’s time to learn from your mistake, then do better.’ I really feel like our job is to rehabilitate them because most of them didn’t have the type of leadership to let them know what’s right from wrong.”

While Canada said she has a strong working relationship with her inmates, incidents such as the April riot at Lee Correctional Institution that left seven inmates dead leave her shaken. No incident of this sort has occurred at Graham in Canada’s time there, but she knows that work is not a place where she can let her guard down.

“You didn’t come to prison for not going to Bible study, so you’ve always got to be alert to everybody because you know it can happen to y’all,” Canada said. “A lot of people think that the females won’t do anything, [but] they do the same type of crimes that males do on the outside. I pray it don’t happen at the female institution.”

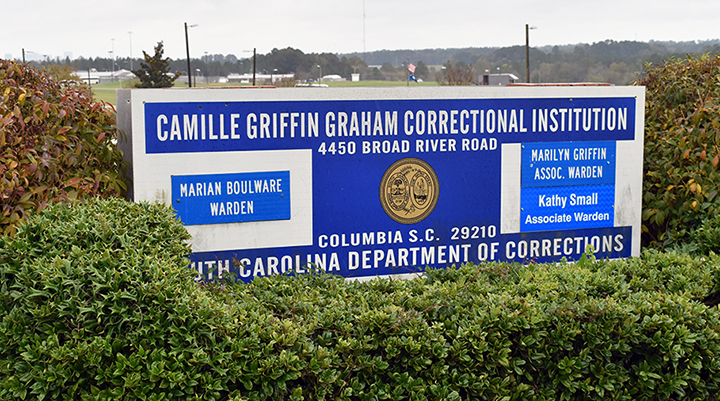

The South Carolina prison system is suffering from a shortage of guards and colorful “now hiring” signs can be seen in the Department of Corrections’ offices and newsletter and near Graham and other state facilities.

In 2005, the South Carolina Protection and Advocacy for People with Disabilities, Inc. was a plaintiff in a lawsuit against the Department of Corrections on behalf of all inmates with mental illnesses. While the lawsuit focused on mental illness healthcare in prisons, it also dealt with understaffing in South Carolina facilities. P&A won the case in 2014, and, since then, the group and the Department of Corrections have talked out a settlement between them.

“Instead of appealing the decision, everyone got together and said ‘Look, this is a problem,'” David Zoellner, the managing attorney for the P&A statewide, said. “A settlement was created and the Department of Corrections cooperated and wanted to see what they could and would do to fix the staffing issues.”

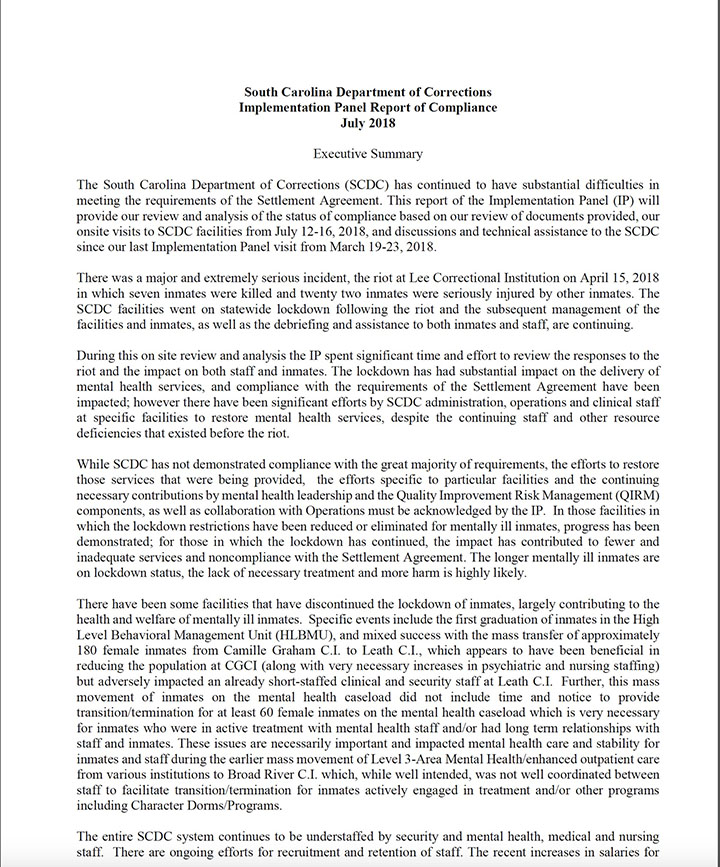

Since the settlement, monitors have been appointed by the court to see if the settlement is being upheld by the Department of Corrections. According to the latest report issued by the monitors in July of 2018, correctional staff in S.C. state correctional facilities for day and night shifts are routinely less than 50 percent of the authorized staffing — meaning that most facilities in the state have critically lopsided ratios of inmates to officers.

But Canada has a job to do.

Every morning, she goes into work, checks her cellphone at the door and readies herself mentally for what could be the best or the worst day possible.

“You could have a good day because everybody is getting along, the inmates are doing what they’re supposed to do. And then today you have some inmates that want to be disrespectful, it just depends on how certain people feel,” she said. “There’s always something new every day.”

A section of the July 2018 monitor report on the status of the state of South Carolina’s progress on the settlement agreement. This report states that the Department of Corrections is not able to uphold its side of the settlement agreement.

Corporal Moldavia Canada has worked as a contraband officer at the Graham institution for eight years. Her job is to screen the facility for items that are not allowed by state government that have been smuggled in by inmates.