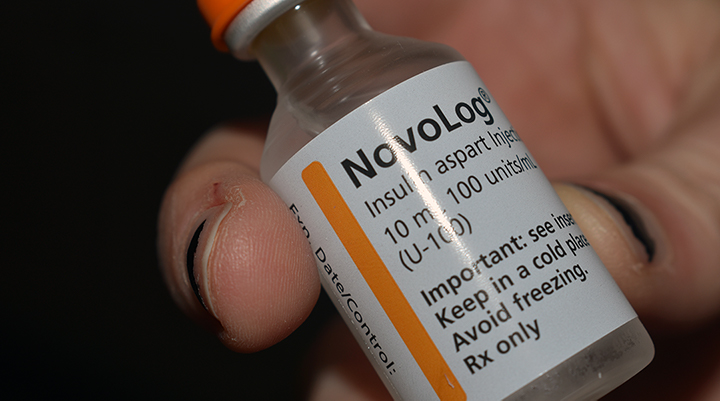

Insulin is a necessary medication for those with Type 1 diabetes, and helps patients to live successfully with diabetes. But it isn’t a cure for the disease.

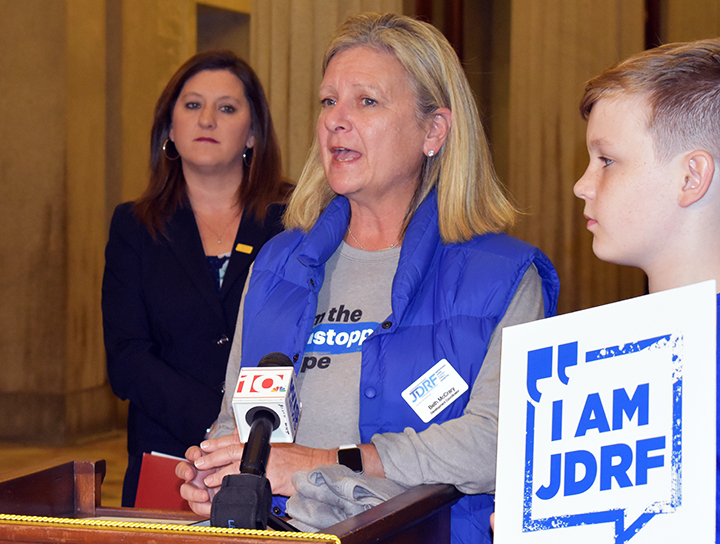

When Beth McCrary’s daughter was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, she became a “mom on a mission.”

Hannah McCrary, who is now 17, was seven years old when she was diagnosed, turning the family’s life upside down. Through Beth McCrary’s work as development coordinator for the Palmetto chapter of the nonprofit Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, she has taken the passion and concern she felt at her daughter’s diagnosis and made a career of diabetes education, awareness and advocacy.

“I was like most people prior to my daughter’s diagnosis with Type 1 diabetes in 2008. I did not take diabetes seriously,” Beth McCrary said. “But there are physical, emotional and financial burdens that come with living with diabetes and all three are huge.”

On Wednesday, as she has done for the past decade, Beth McCrary was at the State House for World Diabetes Day 2018. She was there not only to celebrate those living successfully with the disease, but also to bring awareness to the trials and treatments of the condition — and to its symptoms for those who might not know them.

“One of the most important components of World Diabetes Day is that people know the warning signs of both Type 1 and Type 2 — frequent urination, extreme thirst, sudden weight loss, lethargy,” Beth McCrary said. “It’s also important for someone living with Type 1 to know that if you don’t get immediate medical intervention, you die.”

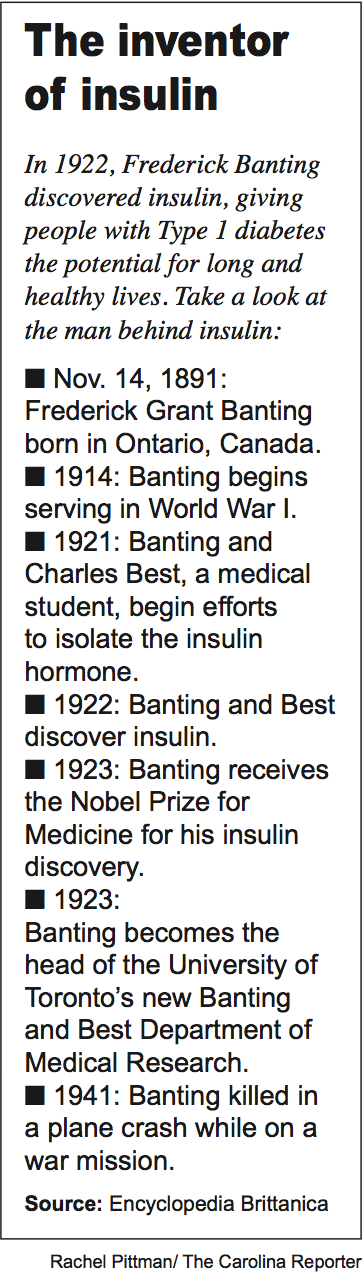

November is Diabetes Awareness Month, with Nov. 14 proclaimed World Diabetes Day as a nod to the scientist who discovered insulin, Frederick Banting, born on Nov. 14, 1891. The objective of both Diabetes Awareness Month and World Diabetes Day is to spread knowledge of a disease that is the seventh leading cause of death for Americans.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2017 Diabetes Report Card, over ten percent of adults in South Carolina have diagnosed diabetes. Around five percent of those diagnosed have Type 1 diabetes.

An autoimmune disease, Type 1 diabetes occurs when a person’s pancreas does not produce insulin; Type 2 diabetes occurs when a pancreas eventually stops producing insulin. Insulin, the hormone that regulated the levels of glucose in the bloodstream, is necessary to maintain healthy blood sugar levels.

“As we take in food, glucose is automatically absorbed into the body,” Dylan Cooper, pharmacist in charge at Long’s Drugs on Millwood Ave., said. “With modern diets, we sometime take up too much sugar and the body regulates that with insulin telling the body’s cells to pull sugar out of the blood. The risk of that not happening is that the sugar builds up in the blood and can cause severe damage to the body.”

While Type 2 diabetes is also a serious condition that requires medical attention, it can sometimes be remedied in full or in part by a change in diet and exercise. Additionally, drugs exist for Type 2 diabetes patients that can be taken orally or injected into the body and that kickstart a failing pancreas, helping it to overcome insulin resistance and produce the needed insulin.

With Type 1 diabetes, exogenous insulin — or insulin that enters the body from outside — is the only answer, and many Type 1 diabetics require a variety of insulins to get through the day.

“With Type 1, you need both rapid-acting insulin before or after you eat to cover the carbs you eat and also slow release insulin which is typically one injection that is released throughout the day to stabilize that insulin level,” Beth McCrary said. “Insulin is not a luxury. With Type 1 diabetes you do not have a choice.”

Evolving treatments

While treatment options are limited for Type 1 patients in comparison to the treatments for Type 2 diabetes, Type 1 diabetics have seen an increase in available treatment options in recent years.

In 2010, two years after her daughter’s diagnosis, Beth McCrary spoke with her congressmen about a then-unavailable artificial pancreas. She and a group of others asked the lawmakers to sign a letter that asked the FDA to speed the process of approving this treatment.

An insulin pump is a device that provides a continuous drip of insulin, keeping a base sugar level stable, while a continuous glucose monitor, or CGM, is a device that takes a constant reading of blood glucose levels.

Though both insulin pumps and CGMs were in existence in 2010, a combination of the two technologies that would form an artificial pancreas was not yet available.

“With an artificial pancreas, the CGM automatically reports insulin levels to the pump to get rid of some of those dangerous highs and lows,” Beth McCrary said. “In 2010, my hope and prayer was that my daughter would have access to that artificial pancreas by the time she went to college in the fall of 2019. She’s a senior in high school currently, and she’s been utilizing that technology for a year and a half.”

Since she began using the artificial pancreas, Hannah McCrary’s blood sugar levels are in range approximately 80 percent of the day, which is double the approximate 40 percent of the time that her blood sugar levels were in range before using this treatment.

For Lake City native Mary Bryant Matthews, 21, advances in both technology and diabetes treatments have allowed her to use a combination of a pump and a CGM application on her iPhone to manage her diabetes. The two devices do not communicate as the pieces of an artificial pancreas do, but instead Matthews is able to get real-time glucose readings on her phone.

“My CGM checks my blood sugar every five minutes and then I see the readings on my phone,” Matthews said. “I just open my app and I can visually see what my blood sugar is, and what it was as far back as 24 hours ago. I can see my blood sugar as it’s dropping or as it’s going up so I can stop those spikes.

Matthews, a fourth-year management student at the University of South Carolina, found out that she had Type 1 diabetes on her sixth birthday. It’s been fifteen years since her diagnosis and, over that time, she’s had a revolving door of treatments presented to her.

For a year after she was diagnosed, Matthews used strictly insulin shots. She then experimented with different insulin pumps until the age of 15, when she returned to using insulin injections. Finally, this summer, she was able to once again find a pump option that worked for her, making her diabetes seem “less invasive” to her life.

“When I was a teenager and in those high school years, I just tried to ignore it,” Matthews said. “Having to pull out my insulin shot or check my blood sugar in the middle of class — it was embarrassing. Now, I don’t have to prick my finger or give myself a shot in front of people. It’s all gotten a lot easier to manage.”

Advanced treatments don’t always work — and can also mean higher costs

While strides have been made in diabetes research and treatments, these new solutions don’t always hold the answers.

This summer, before Matthews found the pump and CGM that was successful for her, she tried using the artificial pancreas technology. However, the treatment that worked so well for Hannah McCrary had different results for Matthews.

“I wanted to go back to using a pump and I saw that there was this new technology where the pump and CGM does basically everything, they work together and you don’t have to think about it,” she said. “I tried it for four months over the summer when I wasn’t in class and could really focus on making it work. And I hate it, but it didn’t work for me. I would get sick and my blood sugar was all over the place because that CGM wasn’t accurate for me.”

Mathews decided to go back to a pump that she had previously used, pairing it with the new CGM on her phone.

Matthews’ insurance company didn’t cover her working pump because of the amount of time that she had used the new pump technology. The company asked for her to try the new system for six to 12 months before deciding not to use it, meaning that Matthews would have spent six months to a year suffering through the negative side effects that she was experiencing. Instead of continuing a method that was unsuccessful for her, Matthews and her family paid outright for the new pump.

With the influx of new diabetes treatments, pumps and varieties of insulins, patients are often forced to try a myriad of treatments before finding the best one, and drug companies are charging higher prices to cover the price of the diabetes research that produced these new treatments and tools.

“A lot of research is going into diabetes right now and with each new treatment, insulin or drug that comes out the maker is able to maintain the patent on it and keep it as a brand name,” Cooper said. “A drug when it’s first made may have ten years where the FDA will say that no one else can sell a drug. When there’s a patent on a drug, the company can charge whatever they want because there’s no one else making it.”

Insurance companies will always cover the cheapest treatments for policyholders, but, in the case of insulin, the specific insulin an insurance company covers might not be the best fit for a diabetes patient, or might not be the one that a doctor prescribes.

The complex arrangement of amino acids that composes each type of insulin also makes it impossible to buy a generic form of an insulin, leaving patients even more dependent on the specific type of insulin that they’ve been prescribed, regardless of price.

“If company A makes short-acting insulin and company B makes one as well, they technically cannot be considered generics of each other so, as a pharmacist, if I get a prescription for one I can’t just change it to the other, although they may act exactly the same in the body,” Cooper said. “There are also times when certain insulin companies give insurance companies price breaks on their insulin, so that affects coverage as well.”

The other medications options available to Type 2 patients do have available generics, making those treatments somewhat more accessible. For Type 1 students, insulin isn’t optional.

“Even ten years ago, insulin was somewhat affordable, but now it’s outrageous,” Beth McCrary said. “There are folks that are rationing insulin because they can’t afford the out-of-pocket cost because of their insurance plan or their lack of insurance. This is a life-saving medication. Type 1 patients cannot live without insulin.”

Moving forward

On World Diabetes Day 2018, Hannah McCrary, Matthews and others affected by the disease aren’t stopping to consider their hopes for the future of diabetes treatments and, hopefully, a cure. For them, thinking about future progress for diabetes is an everyday occurrence, because the disease affects their every day.

“Emotionally, you think about the disease 24/7 and you beat yourself up about decisions you make, thinking ‘I shouldn’t have eaten that, I should’ve checked my glucose levels then,’” Hannah McCrary said. “It’s just a lot to think about all the time.”

At the State House on Wednesday, McCrary joined a group of those affected in some way by Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, all of them clad in royal blue, the awareness color of the disease. State Rep. Garry Smith, R-Simpsonville, gave a speech about diabetes, touching on the increasing number of cases in South Carolina and ending with a World Diabetes Day proclamation issued by Gov. Henry McMaster.

“This is something that we as South Carolinians should be very much concerned about,” Smith said. “The number one cost in the hospitals within the state is complications related to diabetes. If we’re ever going to get our Medicare budget under control, our healthcare under control, that’s something we’re going to have to deal with. From a policy standpoint, it just makes sense.”

Beth McCrary is also concerned with how policy will affect her daughter’s future as a diabetic. With political influences affecting insurance plans and coverage, financial stability for diabetics in the future is uncertain.

“Right now, my daughter can stay on my insurance plan until she is 26,” Beth McCrary said. “But with all that’s going on in the political sphere, who knows if pre-existing conditions will continue to be covered? If that changes, I’m fearful. How will I be able to keep my daughter alive and healthy? How will she be able to afford it?”

In future years, patients are also looking for further advances in treatment technology. Beth McCrary is hoping for a way to prevent anyone else from developing Type 1 diabetes. While this is not a cure for those who already have diabetes, it is a way of protecting the next generation from the disease.

“When you prevent a disease, you in essence cure it,” she said. “It’s not a biological cure but it’s a cure for future generations — for my grandkids.”

But while there is hope for better policy and prevention of the disease, in the end, those living with diabetes are ready, once and for all, for a cure.

“For years, doctors and researchers have said ‘a cure is coming soon, it’s right around the corner,’” Matthews said. “I’ve seen lots of strides made in the technology and medicines for diabetes, but no real strides in finding a cure. As much as I’m told a cure is right around the corner, it’s hard to believe.”

Beth McCrary, the development coordinator for the Palmetto chapter of the Junior Diabetes Research Foundation, has been passionate about raising awareness for diabetes since her daughter was diagnosed with Type 1 in 2008.

The Junior Diabetes Research Foundation is a non-profit that works to increase awareness of diabetes and raise funds for diabetes research.

Pharmacist Dylan Cooper at Long’s Drugs in Columbia fills a significant amount of prescriptions for insulin and has seen the price of the medication rise over the years.

Mary Bryant Matthews, 21, found out that she had diabetes when she was six years old. She now manages her diabetes with the combination of an insulin pump and a constant glucose monitor that is on her phone.

This summer, Matthews began using an app that checks her blood sugar levels every five minutes, allowing her to remedy blood sugar spikes as they happen.

Pharmacies like Long’s Drugs in Columbia carry many brands of insulin. Brand-name insulin varieties do not have generic alternatives, making insulin more expensive for patients.