Erosion is a constant battle for some South Carolina beach towns, threatening beachfront property and tourism-generated economies.

The Morris Island Light reflects the severe erosion that has plagued many of Charleston’s beaches since the construction of the harbor jetties in the 1800’s.

In the fight to save South Carolina’s beaches from erosion, sand-moving equipment is a familiar sight along the coast line.

Edisto Island is one of many locations affected by rising sea levels and erosion along the South Carolina coast. The Seaside building on Edisto Beach overlooks the Atlantic Ocean.

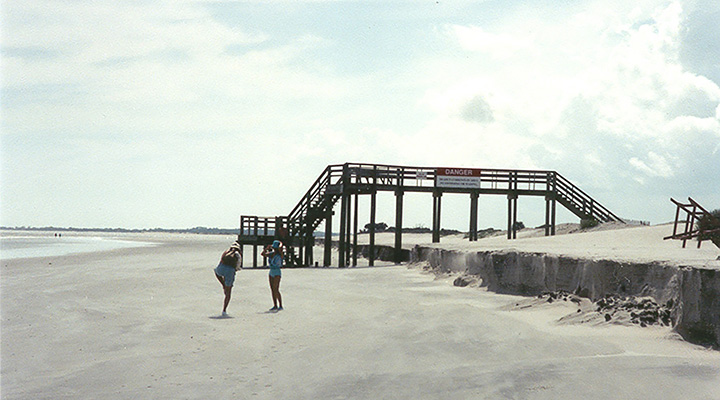

Steep drop-offs of sand indicate erosion on beaches, such as those on Folly Beach County Park.

First in a three-part series

The Morris Island Light, a lighthouse located between the shores of Morris Island and Folly Beach, sits on a tiny, constructed island hundreds of yards out to sea. The lighthouse, with dull fading paint, has been decommissioned for years and now serves as little more than a photo opportunity for tourists.

What tourists, some locals, and newcomers to Charleston may not know is that Morris Island Light once stood more than 1,000 feet from the shoreline. Now it is surrounded by water on all sides, a stark representation of the severe beach erosion that plagues the South Carolina coastline and often outweighs the devastation if hurricanes.

“The shoreline is getting increasingly compressed against our society,” Coastal Carolina University expert Paul Gayes said. He pointed out that sand dunes, which help slow beach erosion and create habitat for animals like sea turtles, cannot form along the shoreline if that shoreline is encroaching on a heavily developed area, which increases as coastal cities like Charleston continues to grow.

“There’s a couple of drivers,” Gayes said on the causes of the erosion. “In the long-term, over decades to centuries, the fact that life at sea level is rising…and there are ways to overcome that. It’s a balance between sea level rise and sediment supply.”

Rising seas may be the long-term problem affecting shifting coast lines around the world, but College of Charleston marine geology professor Leslie Sautter points out an issue specific to the Charleston area, one that Gayes refers to as a “complicating factor” in the system; the Charleston harbor jetties.

The harbor is a massive source of commerce for South Carolina, and the major reason for Charleston’s growth from a small colonial town to the cosmopolitan destination it is today. As commercial ships grew larger throughout the Industrial Revolution, a wider, deeper channel was needed to provide access to the harbor for these ships. The three-mile long rocky jetties were built by the Army in the 1800s to create that channel, but their construction had a few unintended consequences.

Sautter, a coastal erosion expert, described a complex system of rivers, deltas, and currents that transport sediment from one island to the next, a migration that takes years. Longshore drift current is especially important in feeding the beaches sand, and the construction of the jetties blocked that flow of sediment. As a result, many beaches along the Charleston coast have eroded severely since the construction of the jetties, with Morris Island having been affected the most.

“Folly has lost a tremendous amount of sand because Morris Island has lost it all, basically,” said Sautter. “And that means that Folly is going to be the one that goes next.”

The thought of losing Folly Beach – and other beaches along the picturesque Lowcountry coast – is alarming to residents and city officials alike. Beaches are not only home to thousands of locals, they are also a major source of commerce. Tourism is a multi-billion dollar industry for South Carolina (topping a whopping $20 billion in 2017), mainly due to coastal towns like Charleston and Myrtle Beach that draw millions of visitors and generate millions in state taxes and local revenue each year. That makes the loss of these beaches a statewide crisis.

To combat the erosion, federally funded beach re-nourishment projects have taken place since the early ’90s, which involve dumping massive amounts of sand along the beaches to replace the sand that eroded away.

The process, while necessary to slow the erosion, is also extremely expensive. Gayes said that since the first re-nourishment project occurred on Folly Beach in 1993, the process of battling erosion along the coast has costed around half a billion dollars.

It also doesn’t work. While replenishing sand does keep the beaches from being eroded away quickly, it is a short-term solution to a long-term problem.

Hurricanes add yet another complicating factor. Every time a powerful storm hits the South Carolina coast, sand is swept away from the shoreline – in Charleston’s case, sand that cost millions of dollars to put there. Hurricanes Matthew and Irma were the most recent storms that hit Charleston, and each stole thousands of cubic yards of sand from places like Folly, Edisto and Botany Bay.

The erosion process has also affected different islands in different ways; some beaches have seen only a slight increase in the erosion processes, while others are in danger of being entirely swept away.

“It’s really complex… it’s a losing battle,” Sautter said. “If you destroy the jetties, then all the commerce of Charleston goes away.”

Destroying the jetties would also not fix the problem, according to Gayes. While it might slow the erosion, it wouldn’t stop the hurricanes from coming or the sea levels from rising.

“It’s relentless, it’s not going to go away,” Gayes said. “It’s also expensive.”

Despite the complexity of the erosion problem, experts and the U.S Army Corps of Engineers are not going to give up on at least making the erosion process manageable. Studies are constantly being conducted by universities and the U.S. Army Corps to enable a better understanding of the erosion and how to slow it down, and re-nourishment projects are completed periodically to slow the effects.

“There’s going to be a lot of effort put in to protect our major coastal cities,” Gayes said, of sea level rise. “We’re not going to lose New York, we’re not going to lose Charleston.”