Cal Hilsman, clinical case manager at Carolina Survivor Clinic, feels mainstream media can fail to humanize refugees. “At one extreme it says that they are terrorists and the other is that they are helpless,” he said.

By T. Michael Boddie and Reema Vaidya

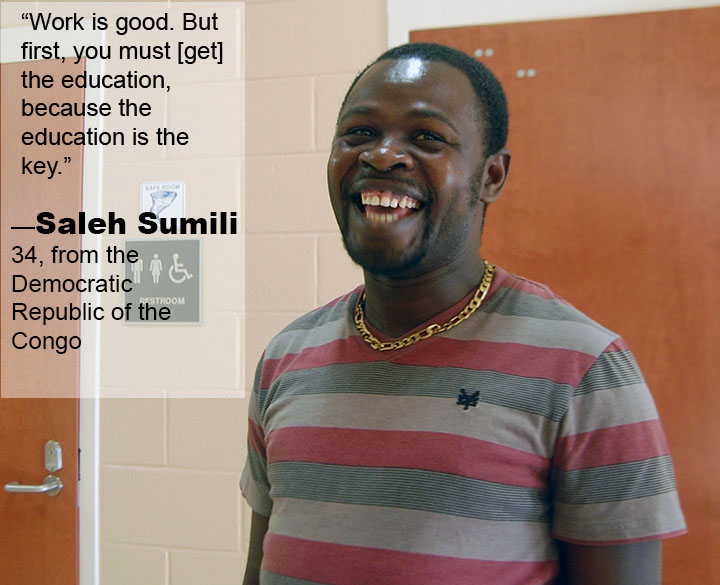

At 15, Saleh Sumili fled his home country, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and took refuge in Tanzania. He made it to the United States about two months ago.

Now 34, Sumili lives in Columbia with his wife and two children and is granted official refugee status by the United States. He is just one of about 900 other people in the city who have sought refuge from their home countries and been granted asylum due to persecution.

Recently, Sumili held a folder close to his body of his own writings. He is still learning to read and write English. He is determined to do so for one reason.

“Education the key. When you are educate, you can help kids, but if you are a parent who is no educate,” he said, speaking in halting English. “They can go to school, and when they come back there is no one who can help them to discuss about their homework.”

The number of refugees like Sumili who are allowed in the United States was capped at 30,000 earlier this month by the Trump administration.

When he announced the new cap, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said the new numbers shouldn’t be considered a measurement of the United States’ humanitarian efforts and that the focus would be on protecting refugees who are already in the country, CNN reports.

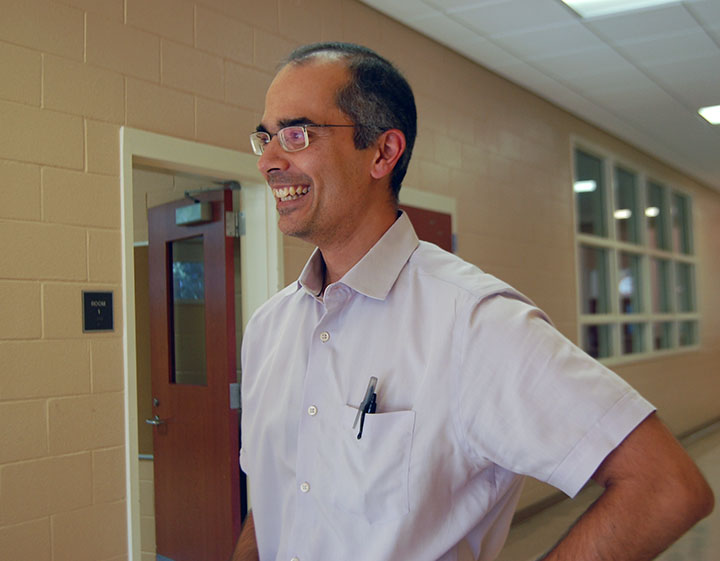

Dr. Rajeev Bais with the University of South Carolina School of Medicine said he is still concerned for refugees who need to come to a new place like the states.

“Truthfully, it makes me wonder what America really stands for. When the majority of America thinks refugees shouldn’t be here, is that right or wrong?” he said.

In 2015, Bais channeled that concern into founding the Carolina Survivor Clinic.

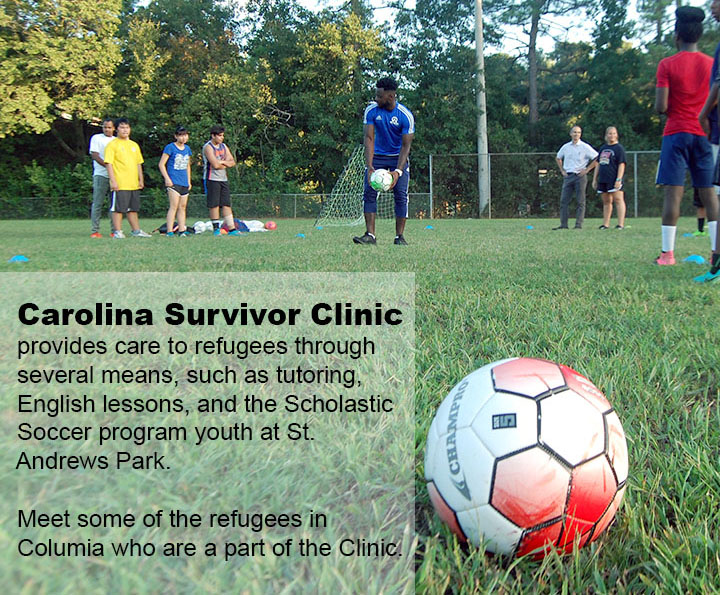

For refugees living in South Carolina, the clinic dedicates itself to providing that protection. In partnership with the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and the Palmetto Health USC Medical Group, the goal is to help refugees who have survived the unthinkable get the care and sense of community they seek.

Cal Hilsman, CSC’s clinical case and program manager, works with refugees to make sure they are adjusting mentally and physically to their new life in the United States. The clinic runs daily programs, recruiting volunteers to tutor refugee children and help them participate in sports.

On Tuesday, Hilsman could be seen helping volunteers tutor children in classrooms at St. Andrews Park and recreation center. While the clinic doesn’t have a specific physical setting, most programs like the tutoring sessions and recreational soccer games take place at the center.

Unsure of what the recent cap on refugee numbers means for the clinic, Hilsman said he is worried for his patients and their kids.

“With me being so invested with this population, I love and care about them. It’s mostly scary for them…these people will not have the opportunity to grow in life,” Hilsman said. “We will see what happens to this clinic and my job, but it is definitely not a good thing.”

Clinical visits with Hilsman or Bais are free to all clients, Hilsman said. Palmetto Health and the USC School of Medicine partner to fund the use of hospital rooms and equipment, and other CSC programs are funded with donations and small grants.

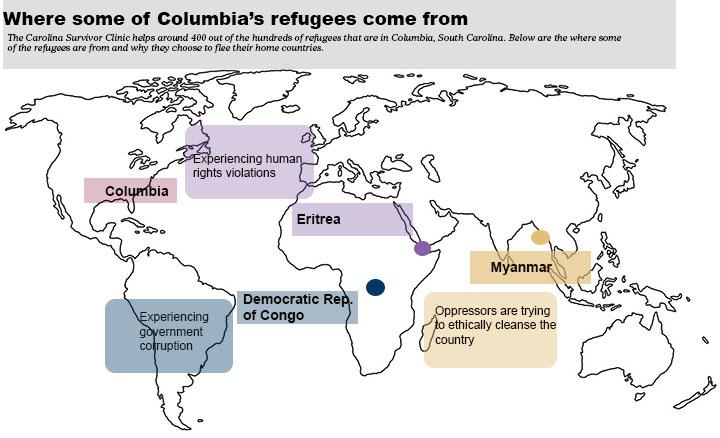

The clinic welcomes refugees from countries that are dealing with oppression and persecution. Most of the refugees who use the clinic’s services are from Myanmar, about 30 percent of the refugees are from the Democratic Republic of Congo, followed by about 10 percent from Eritrea in northeast Africa.

The major difference between a refugee and an immigrant is the reason why they leave home.

In the U.S., people are considered refugees when they have to flee their homelands due to oppression or persecution. In contrast, immigrants choose to leave their country and move to the United States, whereas someone who leaves their country based on a “well-founded fear of returning” is given the status of refugee upon entering the states.

“It’s their home. Of course, they want to go back,” Laura Rudisell, a fourth-year global studies student at USC and a volunteer with the clinic, said Tuesday. “Do you realize how terrible that is to have to see your home amidst conflict or amidst persecution of a certain people?” she said.

Over 25 million people were forced to leave their home countries as refugees as of 2017. Statistically, about 30 people are forcibly displaced as a result of persecution, violence or human rights violations every minute, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

When Bais, now the director of Carolina Survivor Clinic, first arrived in the U.S. wearing his traditional Punjabi garb, he didn’t know any English.

“Nobody helped me; no one knew what I was saying. It was hard,” Bais said. “So imagine what they’re going through.”

War and violence are major reasons refugees seek asylum. Some, including children, have endured torture.

Running the clinic in an effort to help refugees heal from what they endured and witnessed, and to feel comfortable in their current home, is extremely important to Bais.

“We try to focus on limitations of people’s agency. What’s preventing them from reaching their potential?” he said. “So, things like transportation, education … not speaking English, food insecurity.”

Carolina Survivor Clinic not only provides holistic care, like adapting healthy eating habits and lifestyle, but also helps each refugee with their mental growth. Refugees that are fleeing persecution from their home county often deal with anxiety and depression. The clinic allows refugees to overcome their trauma through individual therapy and comprehensive care.

“They experience trauma migrating to a new country, through all that you lose your sense of self and you feel isolated,” said Hilsman. “We can help with their physical health of needs and I help with counseling.”

The treatment does not stop there. CSC also believes that community building and connection is just as important as mental health. They want each refugee to feel included by offering tutoring and English classes, followed by a soccer game as an initiative for the children.

“This is just not a one-stop shop,” Hilsman said. “It’s a continuing approach to work with everyone in the family to build this community of health. It is really like a family. Mindfulness and healthy eating habits are also tied into all of this.”

Carolina Survivor Clinic accepts volunteers to help with the care of each refugee, and they can typically help in any area they choose.

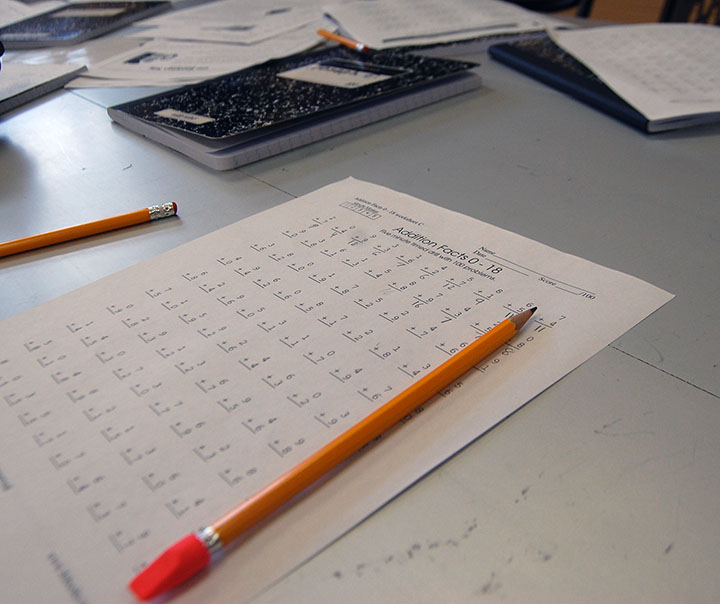

There are 3.5 million school-age refugee children who are not in school, the UN agency said. Volunteers with the clinic will often tutor refugee children in Columbia who are tackling school work and trying to improve their English.

Hilsman says volunteers really have the opportunity to expand explore other cultures and expand their horizons just by immersing themselves and giving their time to these refugees.

Rudisell volunteered with the clinic for several months after studying in Jordan. She said after seeing refugees there, waiting to go to a third country like the U.S., she wanted to be a part of the process of getting those people settled.

“Columbia isn’t a huge city. It doesn’t have an extremely large refugee population. That’s why it’s really important, I think, for Carolina Survivor Clinic to keep doing what they’re doing,” Rudisell said, “because we want the refugees who do get settled here to feel at home. And, basically, what I can do as a volunteer is just be a friendly face—someone they see consistently.”

For more information on how to get involved, visit, columbiarelief.org.

Carolina Survivor Clinic offers weekly tutoring classes for the refugee children and adults. The classes focus on improving their math and English skills.

Dr. Rajeev Bais, started Carolina Survivor Clinic in 2015. He says the Trump administration’s recent cap on the number of refugees allowed in the United States is unethical.

Refugee children play on a playground at St. Andres Park and recreation center in Columbia. The Carolina Survivor Clinic offers children and their parents tutoring and childcare at the center.

While the children are outdoors playing soccer, adult refugees regroup with the volunteers to work on their English and speech skills indoors.

Laura Rudisell, a fourth-year global studies student at the University of South Carolina, volunteers with Carolina Survivor Clinic. She often sits and talks with adult refuges for a conversation hour to get to know them better and help them with their English.