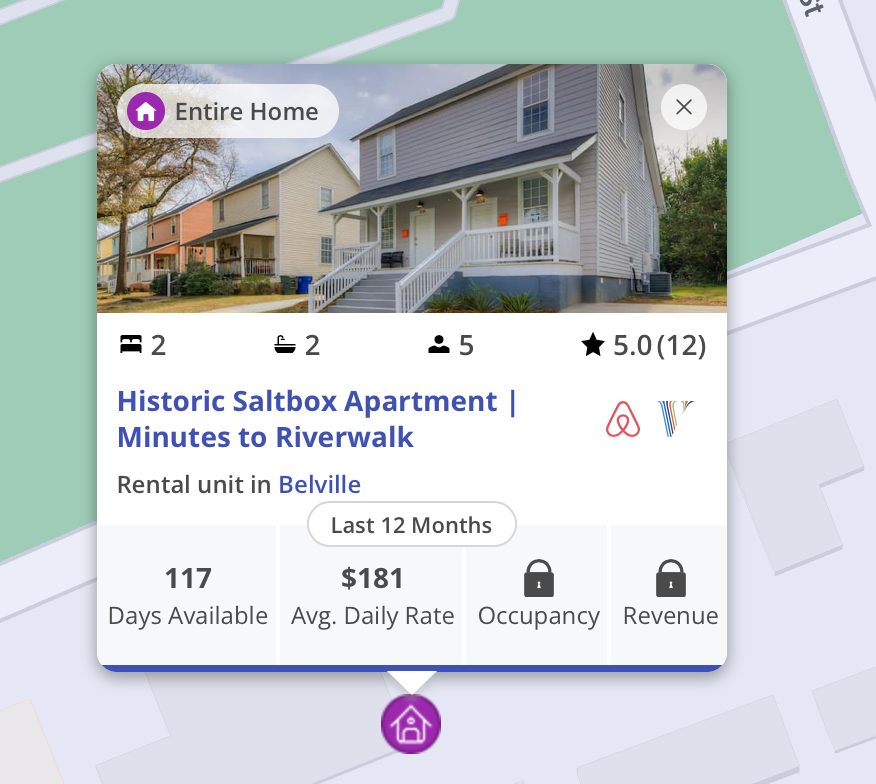

A photo of an Airbnb in the 29201 zip code of Columbia, S.C. There are about 500 short-term rental homes in the city. (Photo by Kailey Cota)

Football fans, college students’ families and traveling professionals regularly flock to South Carolina’s capital city to enjoy a weekend, catch up with loved ones or work for a few weeks.

Visitors book Airbnbs and other short-term home rentals to get a stronger sense of home or lower prices than established hotels.

But as business owners have realized this and broken into the market for renting out homes short term, Columbia’s neighborhoods are becoming more transient, which is only compounded by the more than 60,000 college students who regularly seek year-long rental housing options.

Residents in Columbia’s neighborhoods say they want to know the people living beside them instead of seeing a constant rotation of strangers each night.

“Short-term rentals disrupt the fabric of the community,” Kit Smith, a Wales Garden resident and former Richland County Council member, said at a Sept. 29 committee hearing. “The more that we have, the more the fabric of that community is threatened.”

But people who invest in short-term rentals are pointing out that their businesses are filling a desire visitors have and that well-mannered guests can put money back into the economy.

“We are concerned,” said David Bergmann, owner of the Heartwood Furnished Homes property management company. “We want to have the right regulations for small business owners like us.”

Three Columbia City Council members were tasked with sorting it all out, and committee chairman Howard Duvall gave each stakeholder a seat at the table last week to discuss a new ordinance.

Though they haven’t yet reached a conclusion, Duvall’s goal is to reach a compromise before the first of the year to regulate the industry.

A NATIONAL ISSUE

Airbnb cracked the market open in 2008 when it launched, though VRBO has been around for more than 20 years and was the first platform to list short-term rental offerings online.

Today, Airbnb is the largest platform for the short-term rental industry, with more than 6 million active listings in 100,000 cities worldwide. Any rental listing for less than a month can be considered a short-term rental.

Cities across the country are grappling with the question of what to do with these businesses. Arizona — which initially decided not to regulate the industry — is the “poster child” for what not to do, according to President and CEO of the South Carolina Lodging and Restaurant Association Susan Cohen.

More than 30 Arizona mayors published a report in February 2021, warning other officials to regulate the industry before it eats up too many housing options.

Sedona, a rural but popular tourist location, is one particularly bad example the mayors offered. The report estimated between 10% and 17% of the city’s total housing industry became short-term rentals.

This compounded Sedona’s historically high housing prices, creating affordability issues for the workforce, according to the report. The average home price increased by nearly 50% between 2015 and 2019, and school enrollment declined during the same time period, implying young families were finding it difficult to live there.

These issues aren’t contained to Arizona. They merely reflect the national battle industry leaders and city officials are toughing out.

Vacation rental research company AirDNA lists Charleston, S.C., as the 5th best city in the country to invest in short-term rentals, just behind destinations in Hawaii and Nashville, Tennessee.

There now are about about 2,300 active short-term rental listings in the tourist haven. Home prices jumped by more than 20% last year, according to a May 2022 report from the Charleston Trident Association of Realtors.

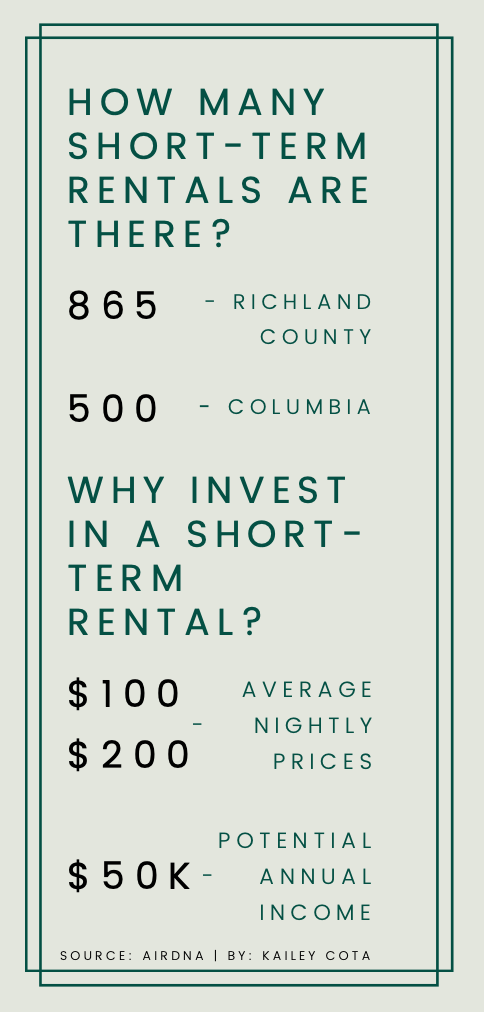

Though Columbia’s can’t measure up to Charleston’s tourist demand, its qualities as a centrally located state capital that’s home to more than 60,000 college students and more than 3,500 active duty soldiers mean there is a market for short-term rentals.

For example, a small, three-bedroom home 10 minutes from the Statehouse and the University of South Carolina, could make an investor more than $50,000 a year as a short-term rental.

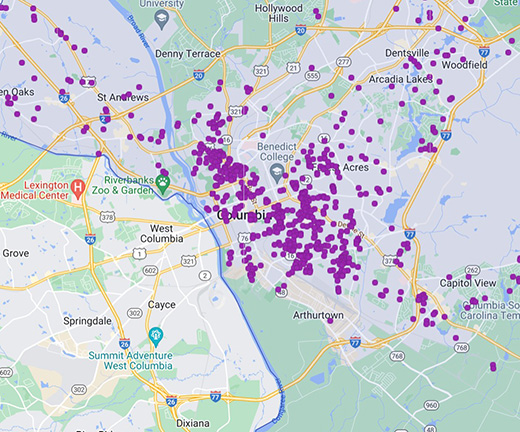

The city does not have data about the number of short-term rentals in the area because it’s still working to create a permitting process. But AirDNA estimates there are more than 860 active short-term rentals in Richland County and 500 within the city limits.

These listings are concentrated in Columbia’s 29201 and 29205 zip codes. They’re the central, tree-lined, more historic areas of the capital city.

COLUMBIA CONCERNS

Christine Edwards rented a home in the 29201 zip code for a weekend in October to reconnect with her adult children, who live across the state.

The Edwardses chose to stay in an Airbnb instead of a hotel to get away from the bustle of the city and feel more at home.

“We were looking for a place that had room for all of us, privacy for them, privacy for me, and you get that with an Airbnb that you can’t necessarily get with a hotel,” Edwards said. “It’s a lot more like a home, but just away from home.”

Jenna Hurlburt, a third-year psychology student at the University of South Carolina, lives in the duplex next door to the Airbnb Edwards rented.

This is her first year renting the apartment, but she plans to continue through her senior year. She knew her neighbors would be short-term renters.

“I don’t mind having them there,” Hurlburt said. “The only thing that does creep me out a little bit is that we do have new people coming in and out each week.”

She said the short-term neighbors don’t always understand when she and her friends are tailgating outside and get dressed up to go to USC football games. But none of the renters have been loud or polluted the street with trash.

And a convenient perk of Hurlburt’s next door neighbor being an Airbnb is that her parents rent it for their visits to Columbia.

“It’s convenient for when our parents come,” she said.

Each neighborhood in Columbia is different, though, and Cohen says established residential neighborhoods could be more disrupted by short-renters than college students, who are also transient.

When you buy a home in an established residential neighborhood, you expect your neighbors also to be permanent residents, many say.

“If that house next door turns out be a short-term rental, you don’t have the same feeling of safety and camaraderie that you would if it was a neighbor who you can go borrow a cup of sugar from, or help take care of their dogs while they’re on a vacation,” Duvall said.

And while residents have personal concerns with the short-term rental industry, hotels have business concerns, too.

Hotels and short-term rentals are competing for the same customer. This is good, Cohen said, because it encourages each business to be the best, but short-term rentals have fewer regulations than hotels do.

Short-term rentals don’t have the same inspection and amenity requirements hotels must have, such as inspections, safety features and certifications. They also don’t currently have the same tax accountability.

This allows short-term rentals to charge lower prices, Cohen said.

“Why would we have to compete with these people who don’t have to have all of the same safety regulations and certifications?” Cohen said.

Not only does the industry impact individuals, but the increase of short-term rentals could be contributing to the overall increase in housing prices, experts say.

“We are very, very challenged with affordable housing across the state, which is exacerbating our workforce issues,” Cohen said. “So, wouldn’t it be better if someone was investing in those properties as affordable housing options for our workforce?”

What’s more, Duvall said, houses are being converted into short-term rentals more quickly than they’re being built for full-time residents.

COMPROMISE IN THE WORKS

The three-person committee, composed of Duvall and fellow council members Tina Herbert and Will Brennan, has spent the past year working to sort out what to do with Columbia’s short-term rentals.

Two key concerns prompted the committee to form. First, the council had heard of loud guests disturbing residents. But it also had noticed investors buying houses for well above asking price to renovate for short-term rentals.

The group most recently held a public meeting Sept. 29 to allow stakeholders from each side to come together and voice their concerns about a draft ordinance.

“(The neighborhood representatives) don’t think it’s tough enough,” Duvall said. “(Short-term renter representatives) think it’s too tough.”

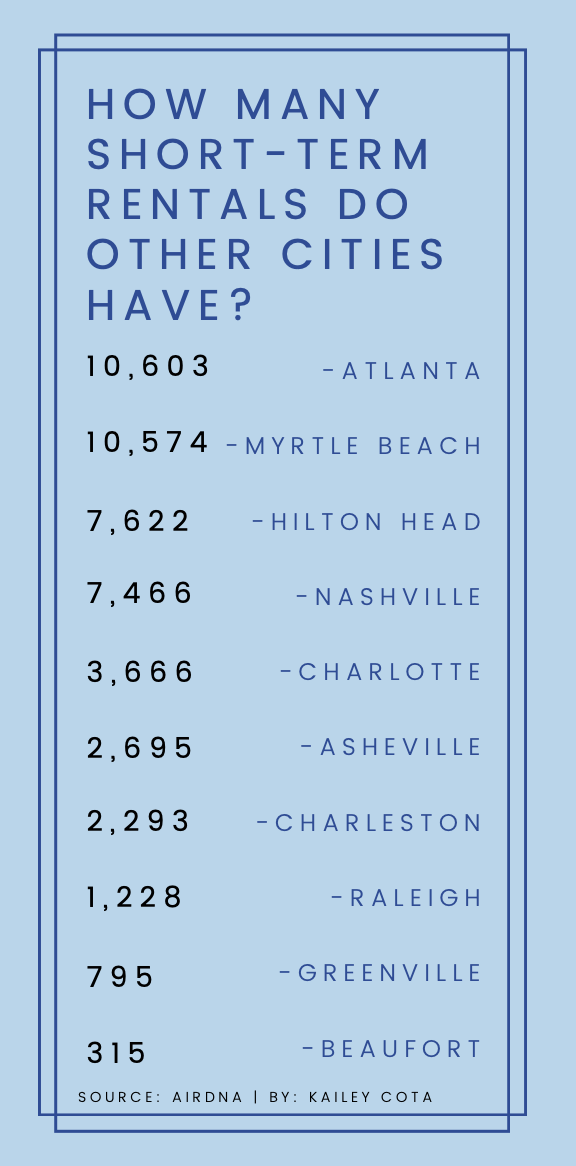

The committee began its work by looking at how other cities, such as Charleston, Hilton Head, Beaufort, Asheville and Raleigh regulate the rentals.

Columbia has fewer short-term rentals than each of those cities, except Beaufort. Hilton Head Island has the most short-term rentals, with more than 7,600. Beaufort has about 300.

The proposed ordinance allows a window of opportunity for all short-term rentals to register and get a permit from the city. No one else would be allowed to apply for a permit after the window closes.

Duvall initially hoped to shrink the size of the market in residential areas. But Bergmann and other industry leaders would like to keep the size of the market the same.

In an attempt to reach a compromise, Duvall met with leaders from the neighborhoods and the industry last week to hash out the draft together.

“Until this point, as stakeholders, we’ve been on the receiving end of the information,” Bergmann said. “(Duvall) heard that we wanted to be involved. … We’re now feeling like we’re being heard a little bit more.”

Questions of what the permit window will look like, if people can apply for permits after that window and if investors have to apply for both short-term and long-term permits are still up in the air.

Duvall plans to meet with stakeholders once or twice more, until everyone is happy with the wording of the ordinance. Then, the committee will hold a public hearing and vote whether to send the ordinance to the entire City Council. The council could then finalize the regulations and start gathering data to fine-tune the process of regulating short-term rentals.

Duvall thinks the group will finish creating the ordinance in the next month and hopes to finish the entire project before the new year.

“I pledged that when we end the process, everybody will be satisfied that we will come up with a compromise that works for both the neighborhoods and the short-term rental industry,” Duvall said. “And I think we’re well on the way to doing that.”

A screenshot of an Airbnb listing in Columbia, S.C. The college students who live in the next-door duplex haven’t had any issues living next to a short-term rental. (Courtesy of AirDNA)

An infographic with data about short-term rentals in Columbia, S.C. AirDNA is a resource for vacation rental information. (Graphic by Kailey Cota)

A screenshot of a map of short-term rentals in Columbia, S.C. AirDNA estimates about 500 homes are being used as short-term rentals in the city. (Courtesy of AirDNA)

An infographic with data about short-term rentals in Columbia, S.C. AirDNA is a resource for vacation rental information. (Graphic by Kailey Cota)

A photo of a short-term rental listing in the 29205 zip code of Columbia, S.C. The Heartwood Furnished Homes property management company owns the property. (Photo by Kailey Cota)

A screenshot of an Airbnb listing in the 29205 zip code of Columbia, S.C. The owner of the property management company is working with the city council to create short-term rental regulations. (Courtesy of AirDNA)