The former Carver Theatre and Royal Motel on Harden Street, built in the 1960s, have sat vacant for decades. (Photos by Camdyn Bruce/Carolina News and Reporter)

Columbia Mayor Daniel Rickenmann hopes state legislators will draft legislation next year allowing counties to gradually lower businesses’ property taxes.

In South Carolina, businesses have a higher property tax rate than residential homes, resulting in thousands of dollars more taxes for business owners than homeowners.

Under the current tax structure, a business in downtown Columbia valued at $500,000 would pay $14,473 in property taxes while a house in the same area with the same value would only pay $3,636 in property taxes.

Higher taxes on businesses in the Capital City also have resulted in slower growth in Columbia compared with other large cities in the state. Those higher taxes have led to stagnating property values and higher operating expenses for local businesses.

Clarke Ellefson, who owns the Lewis and Clark lamp and art shop in the Vista, paid $13,435.77 in property taxes on his storefront this year. He said higher taxes make it harder for businesses to turn a profit.

“It’s going to hold you back,” Ellefson said. “It’s money you can’t put in marketing or tools and equipment and things like that. It’s definitely a drain on the business.”

Rickenman and City Councilman Ed McDowell Jr. in 2022 created what they called a tax modernization committee. The committee drafted a plan to gradually lower property taxes for businesses in Columbia to the same rate that homeowners pay.

Property taxes are regulated at the county level, and Rickenmann said he presented the plan to several high-ranking Richland County officials roughly a year ago. The mayor said he’s optimistic that they’ll present the plan to the state Legislature during the session that starts in January.

“I do believe, in 2024, during this legislative season, we are going to be actively pushing this,” Rickenmann said.

Rickenmann’s plan assumes a revenue growth of at least 2% for the city annually to offset a gradual cut in the business property tax rate over 10 years. During the first two years of the plan, the tax rate would remain the same. Any excess money generated from growth would be added to an escrow fund and returned to business owners at a later date as a tax credit.

Under his vision, as revenue grows, the tax credit available would gradually go up each year until it effectively reduces the county’s 6% commercial property tax rate for businesses to the same as that of homes, which are now taxed at 4% of their value.

County officials said they want to further study the plan before advancing it. Rickenman said he would use city funds to help pay for any study.

“We’re willing to pay for 50% of it because it’s so important,” Rickenmann said.

Rickenmann also said he wants the state legislature to create the program so other counties could opt in, too.

Columbia businesses hit harder than others in the state

Columbia businesses pay more in property taxes than businesses in other major cities in the state.

Property taxes vary across the state because of taxes levied separately by each county and school district.

The county tax rate for Richland in 2022 was about double that of both Greenville and Charleston counties.

A business owning a property valued at $500,000, then, paid $17,629 in property taxes if located in Richland 2, and $14,473, if in Richland 1.

A business with a property of the same value would only pay $10,176 in property taxes in Greenville, and $7,922 in Charleston. Both counties have countywide school districts.

Five Points real estate developer Richard Burts said this has resulted in developers choosing to pursue projects in other major cities with lower taxes rather than investing in Columbia.

“I could go and build or buy something in any state, right?” Burts said. “We want to be able to invest here, but I can invest anywhere. Why should I invest here?”

Rebecca Gunnlaugsson, chief of staff for the South Carolina Department of Education, formerly worked as an economist for the firm Acuitas and conducted a study in 2020 detailing Columbia’s sluggish growth.

She said the state legislature’s passing of Act 388 in 2006 caused the steady rise in tax rates in the Richland school districts.

Act 388 makes it illegal for counties to raise a property valuation more than 15% over five years and also prevents schools from levying taxes on residential homes for operating costs. Homeowners still pay for school districts’ construction costs.

Gunnlaugsson said school districts rely on businesses to pay for their operating costs.

“Basically commercial properties, rental properties, second houses, all bear the additional burden,” Gunnlaugsson said.

Complicating matters more in Richland is the fact that many of the most valuable parcels are owned by the University of South Carolina and Prisma Health Hospital, which are tax-exempt public entities.

According to Gunnlaugsson’s 2020 study, Columbia loses about 24.5% of the potential property taxes it could be collecting due to tax-exempt properties.

Rickenmann said the financial disincentives to develop in Columbia have resulted in the city growing slower than others in the state.

“I will just tell you that when you stand at the top of the Capital City Club and you look across the city and you see all these empty parking lots, all of that could be buildings, growing,” Rickenman said.

Stuck in a Negative Cycle

Gunnlaugusson said high property taxes not only dissuade developers from building new storefronts and housing but make it less profitable for them to renovate existing buildings.

“What happens is property values start to decline or stay stagnant because you don’t have small business owners clamoring to come and buy properties or rent properties,” Gunnlaugusson said.

Will Kitchens serves as the director of finance for the local Cason Development Group, which recently turned a church on Rosewood Drive into an apartment complex and retail space.

He said lower commercial property taxes would encourage more local developers to buy and refurbish older buildings, raising the property’s value.

“I think the biggest benefit would be more transactions of existing buildings for redevelopment,” Kitchens said. “Those sometimes can be trickier to lease since it’s not brand new. And some folks want a brand new building.”

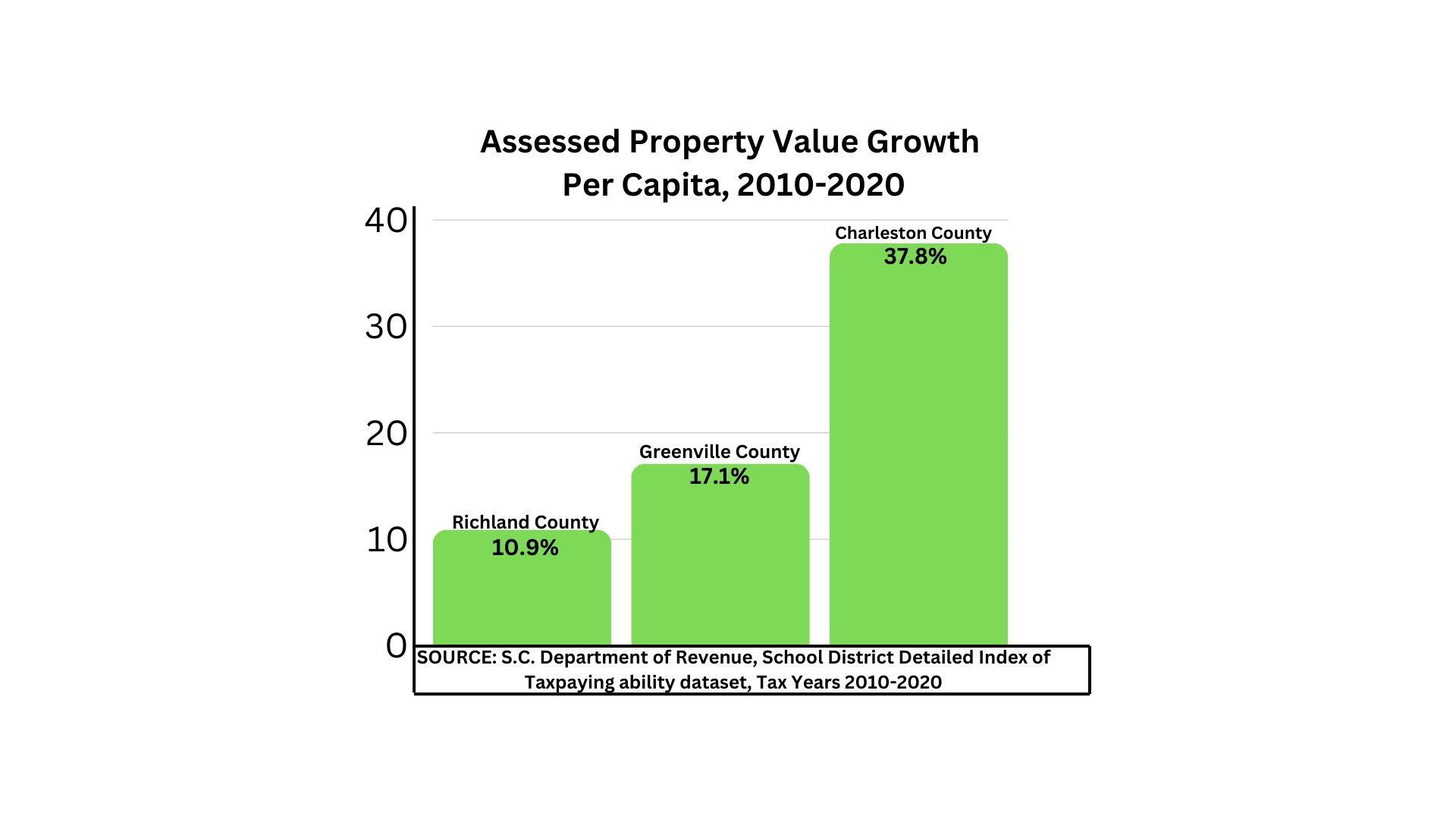

Between 2010 to 2020, property values in Richland only grew 10.9%, compared with 37.8% in Charleston and 17.1% in Greenville, according to data from the S.C. Department of Revenue.

Gunnlaugusson said if property values stay low, officials are likely to keep business tax rates high, to fund schools.

Rickenmann hopes lower taxes will spur development, bring in more revenue and raise property values.

Local developers and businesses hit the hardest

As a temporary fix to combat Columbia’s slower growth in 2019, the county started offering 10-year tax caps – or in some cases, abatements as high as 50% – for projects costing $30 million or more.

Burts said this hurts local developers’ ability to compete with bigger, out-of-state development companies.

“I don’t mind that they’re using these tax abatements to promote growth,” Burts said.

But Burts questions why the tax abatements aren’t extended to smaller projects.

“Why can’t it be a million dollars? Why do you get it, and I can’t get it, because I don’t have $30 million to spend,” Burts said.

Kitchens said the county bases a property’s valuation on the building’s most recent sales price.

He said there are instances in which similar properties are side by side, but one is taxed far more because it was sold recently at a higher price.

“When you buy a property and invest in it, it means you’re going to be taxed a lot higher than other properties that might not have sold but might be kind of the same layout,” Kitchens said.

Kitchens said higher taxes lead to higher rents imposed on tenants leasing storefronts.

“When you purchase a new property to offset the increased tax, you often have to kind of bring rents up to help bring that up to the new purchase price,” Kitchens said.

Kim Gagliardi, who is a co-owner of the Random Tap pub, said high taxes and rents put mom-and-pop restaurants and bars at a competitive disadvantage with big franchises that have more flexibility when downturns strike.

“We aren’t a big corporation with deep pockets, sourcing income from lots of different streams,” Gagliardi said.

She said a bad month could result in local businesses not being able to pay rent or property taxes.

Gagliardi owns the property for Random Tap and said high taxes also make it more difficult for her business to make improvements.

Ellefson said high taxes can sometimes cause businesses to leave Columbia. He pointed to the Copper Horse distillery, which used to own a building next to his shop.

“They decided to move to North Carolina because of the taxes,” Ellefson said.

Rickenman said he hopes his plan will help keep local businesses in Columbia.

“You want to have local businesses. You want regional chains,” Rickenmann said. “A guy who owns a restaurant in Greenville and Charleston, we want him to have a restaurant here, too.”

Will the plan pass

Rickenman said he presented the committee’s plan to county officials about a year ago, but it’s unclear where the plan stands.

Richland County Council Chair Overture Walker did not respond to multiple requests for comment from The Carolina News & Reporter.

Richland District 5 County Councilwoman Allison Terracio said she was unfamiliar with Rickenmann’s plan.

“It’s not really anything that has been formally presented to us as a, ‘Hey, do we want to go in on this plan so that the city and the county are aligned?’” Terracio said.

Terracio also threw cold water on the idea of the state legislature getting involved.

“Have you been to the legislature?” Terracio said. “All they want to do is stuff that has nothing to do with improving the lives of South Carolinians. So, I seriously doubt the legislature is going to do anything.”

Burts said he thinks Rickenmann is sincere in his efforts but acknowledged change is often a slow process.

“Will it come? Probably, probably not, maybe, in my lifetime,” Burts said.