On average, Harold Geddings makes around $150 for each shift he drives for Uber Eats. (Photo by Char Morrison)

It’s 4 p.m. on an overcast Saturday in Columbia.

College students are getting ready for finals, sports fans are watching football games and 45-year-old Harold Geddings is starting his work day as a delivery driver.

After a quick stop for gas and snacks, he drives to Garners Ferry Road — an area of Columbia littered with fast-food and fast-casual establishments.

Geddings works full time for Uber Eats, delivering food in the Columbia area. He sees each day what Columbians eat, how restaurants work and how technology is — or isn’t — keeping up with demand.

Uber Eats, a division of Uber, has been around since 2014. According to Uber’s website, drivers make a base pay per order (calculated by pickup, drop off, time and distance) plus tips and any promotions.

Geddings is a sheet metal worker by trade, but left the job when his “height” vertigo got worse. That was in 2021. He’s been driving for Uber Eats ever since.

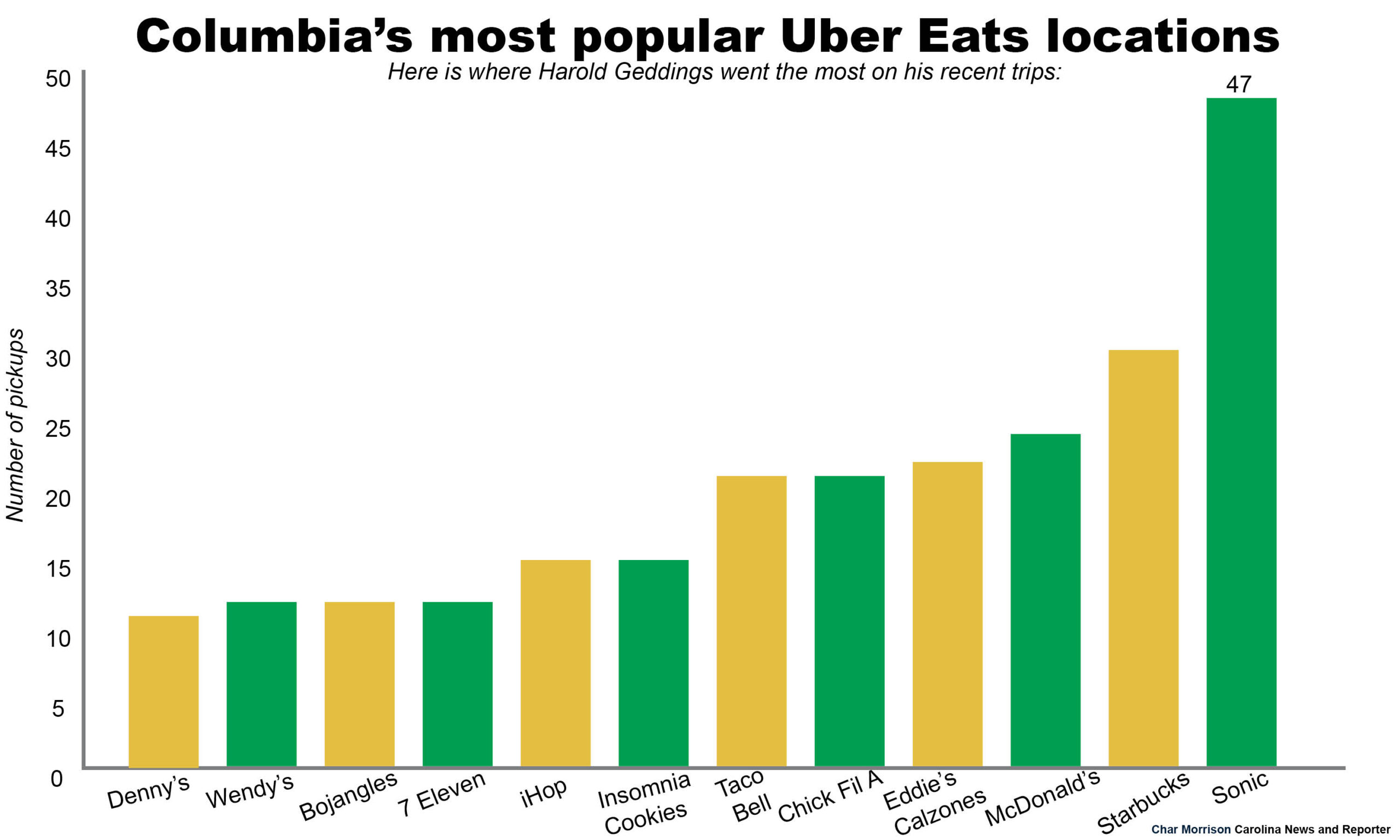

“I’m close to 6,000 trips at this point,” Geddings said.

He completed each of those 6,000 trips in his blue 2019 Chevy spark, which he calls Elbie. Geddings said each shift puts around 300 miles on Elbie, who has already racked up over 151,000 miles.

Other than discounts at certain service locations, Uber doesn’t help drivers with car maintenance.

Geddings groans at his first order of the day — McDonald’s.

“God, I hate that place with a passion,” he said.

Geddings said that specific McDonald’s often has computer problems, requires cash only or doesn’t have the item on the order. Sometimes, the app tells him the restaurant is open only for him to discover it’s closed when he arrives.

“I would just waste my time going there like every freaking night you know, just have to cancel the order,” Geddings said.

Uber Eats drivers don’t get paid for canceled orders, which can put a dent in their earnings. He makes about $150 each shift.

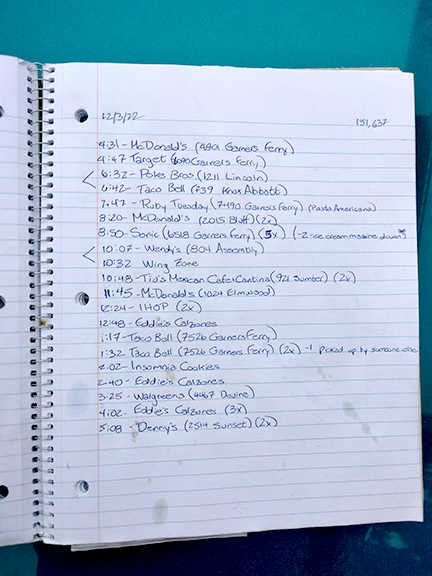

On this day, with a Carolina News & Reporter tagging along, the order at McDonald’s goes smoothly. As he pulls into the parking lot, Geddings takes out a pen and piece of paper and writes down the time and location of the order. Uber doesn’t require drivers to keep a log of their orders. But Geddings said he does it so if he has an issue with a delivery he knows exactly when and where it was.

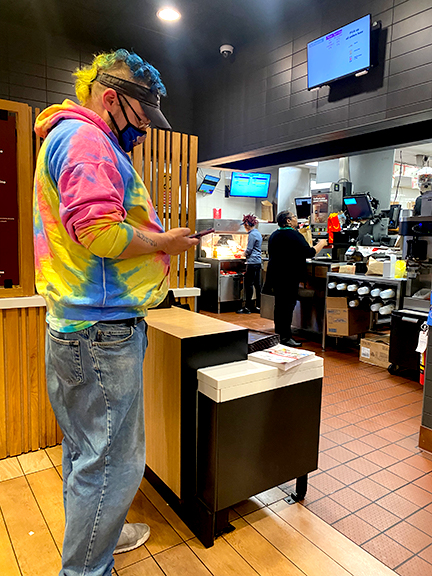

Geddings waits inside the restaurant, wearing a pink, yellow and blue tie-dyed sweatshirt that matches his blue and yellow hair, cut in a mohawk style.

After a short wait inside, Geddings was on his way to deliver a strawberry and creme pie, an Oreo McFlurry, and a six-piece McNugget order to Fort Jackson. Delivery drivers for apps such as Uber Eats can get special permission to deliver on base. (Carolina News & Reporter waited at a nearby strip mall until Geddings returned from the base.)

Delivery drivers for most delivery apps — Uber Eats, Doordash, Grubhub, GoPuff and Instacart — are considered independent contractors, not employees. That allows drivers flexibility when they work. But it also means they don’t get a consistent wage.

Erica Von Nessen, a research economist for the South Carolina Department of Labor and Workforce, said, too, that gig workers aren’t usually eligible for unemployment benefits that people in more traditional jobs are.

“If they lose their job, that’s it. They’ve got no kind of backup,” Von Nessen said.

Even if they don’t lose their job, drivers have no opportunities for promotions.

“There’s really no career path for people who work in gig jobs,” Von Nessen said. “You’re not forming long-term relationships with potentially other co-workers or mentors.”

Uber Eats does offer free online college through Arizona State University to Uber Pro drivers who have completed 3,000 trips or more.

Geddings plans to take advantage of the program next year to pursue a communications degree.

After he finishes delivering the McDonald’s order, he gets an order for a grocery pickup, one of Uber Eats newest features — and one of Geddings’ least favorite aspects of the job.

Drivers always can reject the order, but they run the risk of not getting as many orders in the future if they do that too often. Geddings knows this, and thus has a delivery acceptance rate of 99%.

Geddings gets no pay increase for grocery store orders, despite them often taking more than double the amount of time for a restaurant delivery because he has to shop himself. Uber Eats couldn’t immediately be reached for comment about Geddings’ criticism.

“This thing’s going to take a f****** hour, you know? And unless the customer’s feeling particularly generous, I’m going to make less than minimum wage for doing this,” he said. “So I’m going to miss out on all kinds of other s*** because I got to do this.”

He also mentioned that the stores are often out of items customers want, and he can’t replace them with a similar item until the customer responds on the app, which doesn’t always happen.

But because Geddings doesn’t want to reject orders, he goes through with it and makes his way to the Target, also on Garners Ferry Road.

The customer’s list isn’t too long this time — around 10 items. Target is already out of the first item on the list — 85%/25% ground beef. He messages the customer and moves on to the next item while he waits for a reply.

Around half of the items were in stock. The rest were substituted or canceled. He said this is the easiest a grocery order has ever been for him.

On the way back from delivering the Target order, Geddings mentioned one of his oddest deliveries.

He helped rescue cats and got a request to deliver a cat to its new home — in Pennsylvania.

“Just for whatever reason, (she) wanted this cat,” he said.

After being offered $1,000 for the job, Geddings hit the road.

The cat, named Sammie, hung out in a giant carrier in Geddings’ passenger seat for the trip.

“The cat was cool as hell,” he said. “But was very opinionated.”

The cat would meow if he changed the radio station, hit a rumble strip on the interstate or roll down a window.

After a 13-hour drive, Geddings arrived at the cat’s new home. The delivery went smoothly, though the new owners didn’t seem interested in his trip.

“As soon as I got there, her husband came around the side of the house and met me. He grabbed the cat and disappeared back inside the house,” he said, expecting more excitement from Sammie’s new owners.

Back in Columbia, Geddings spends the rest of his Saturday night picking up and dropping off food, mostly to customers at Fort Jackson.

According to his log, most of the deliveries were late-night fast food, such as McDonald’s and Taco Bell.

At 5:08 a.m., he made his 28th and final delivery of the night, from Denny’s.

After that, he drives to his home in St. Matthews — 30 minutes south of Columbia — which he shares with two housemates, three cats, three dogs and five chickens.

He has the next 12 hours off. But his only plans are to make some food, feed the dogs, check his phone and go to bed.

In about 12 more hours, he’ll be back in Elbie for another shift.

Geddings shows his Uber Eats driver app. The arrows show him popular areas where he’s most likely to get the most orders. (Photo by Char Morrison)

Geddings used to be a sheet metal worker but left the position in 2021 due to his “height” vertigo. He now drives for Uber Eats full time. (Photo by Char Morrison)

While not required of him, Geddings likes to keep track of each order during his shifts. (Photo courtesy of Harold Geddings)