BISHOPVILLE, S.C. – Pearl Fryar, South Carolina’s internationally-acclaimed topiary artist, and the garden he has nurtured for years are alive and well.

Ask Mike Gibson, the Youngstown, Ohio, native who now tends the iconic clipper’s gardens. He moved to South Carolina in August to undertake a renovation of Fryar’s gardens in the 81-year-old’s signature style. If Gibson needs guidance, Fryar is only steps away in the home that adjoins the gardens that have drawn thousands of visitors.

Gibson, 35, first visited Fryar’s celebrated topiary garden in 2016. Gibson, who calls himself a “property artist,” heard about the garden from his father, who is also an artist.

“I started trimming at seven; by 10, I was doing the neighbors; by 12, I was doing people in the community,” Gibson said. “Eventually, my dad said, ‘Son, if you’re gonna do this, you need to check out this Pearl Fryar guy.'”

Before joining Fryar, Gibson had been successful in his own right. In May, he starred on HGTV’s competition show Clipped alongside seven other topiary artists, earning himself the nickname “Gibby Siz.” He has also created hundreds of sculptures around his Ohio hometown, as well as his own brand, Gibson Works Property Art.

After his initial visit to Fryar’s garden, Gibson made sure to visit at least yearly, even proposing to his future wife, Brittanny, there in 2018. But Fryar’s declining health and the COVID-19 pandemic prevented Gibson from returning to the garden. In that time, Fryar became unable to tend to the garden in his traditional style, and so the garden fell into some disrepair.

Hedges became overgrown and were in danger of losing their carefully unearthed shapes permanently. One of South Carolina’s most organic historic landmarks was about to return to nature.

Fate: Yard of the Month

Driving down the Bishopville road to Fryar’s garden, hedge-bush signs on both sides of the highway marks the entrance, A forest-green sign surrounded by elegant topiary greets visitors as they approach. Arriving at the garden, there’s no parking lot except an empty lot across the street, which Fryar’s neighbors offer to visitors.

The garden, which surrounds the home Fryar and his wife, Metra, share, is painstakingly detailed. The care that has gone into the landscape’s creation is self-evident.

“Every rock in the driveway, Fryar put it there,” Gibson said. “All of his trees started out as ten-gallon pot plants.”

The process of turning a home into an internationally-recognized garden began in 1981, when Fryar moved to South Carolina to work as a factory engineer for Coca-Cola, a job he would keep until his retirement in 2006.

Fryar initially wanted to buy a home within Bishopville city limits to be closer to his work. The all-white neighborhood he wanted to buy in discouraged him from doing so, Gibson said.

“He was denied the house because they felt he wasn’t going to upkeep his yard,” Gibson said. “There’s a bad stigma, uh, that black people don’t keep up their yards.” So, Fryar had a home built on the outskirts of the city and set out to prove them wrong. He began going to nurseries, picking up discarded plants and bringing them home. During one visit, Fryar saw a man cutting a bush into strange shapes. Intrigued, he asked for a quick lesson.

“Pearl came home and cut up every bush he had, just started cutting, and then he would go back and get more trees and start playing and he caught the bug. He couldn’t stop. He just obviously couldn’t stop,” Gibson said, gesturing to the hundreds of sculptures in the garden.

Pearl’s goals escalated as he set his sights on becoming the first African-American honoree of the Yard of the Month award given by Bishopville’s Iris Garden Club.

“That’s when he had a mission,” Gibson said, “He thought, ‘I need to show the city and everybody else that not only can I keep my yard, I’m going to do something so creative that nobody ever, nobody will even think of this, nobody can duplicate it.’”

Fryar pursued the award relentlessly. When he wasn’t working in the factory, he would clip his hedges, standing on a homemade scaffold on the back of a truck to reach the higher trees. As his garden grew, he spent more and more daylight hours speaking with intrigued visitors, and worked long nights to make up the difference.

“He’d use the headlights on this car to shine light, he would drive it around and shine light on the bushes so he could keep trimming. They say he’d trim to two o’clock in the morning. I don’t know that I’d want to have been his neighbor then,” Gibson said, chuckling.

Four years later, in 1985, the award was his. Fryar set his garden apart using nearly-composted plants, often without fertilizer or pesticides.

From there, Fryar’s career skyrocketed. He was featured in Smithsonian magazine, became the subject of an award-winning documentary called “A Man Named Pearl,” and embarked on a nationwide lecture series.

“If there’s any situation where you can make a difference, I think we should do it,” Fryar said in an SCETV interview. “That’s how we change our society… it’s always one person at a time. If I have just made one difference in one person, then it’s worth it all.”

Jerry Law, a retired interior designer from Bishopville, accompanied Fryar to a lecture at a conference hosted by Southern Living magazine. Law said she has known Fryar for over 35 years, after meeting him almost immediately after his arrival in Bishopville.

“We both had kind of an artistic mindset, so we formed a fast bond,” she said.

At the conference, Fryar was “a rock star,” she said. “We couldn’t even walk around because of all the people coming up to Pearl. Everybody wanted to talk to him, and you could tell he was thriving off it.”

The lecture Fryar gave illuminated his core philosophy, Law said.

“The fact he created a garden out of what other people would throw away… that’s what he wanted people to do with their lives and with each other,” Law said.

With this goal in mind, Fryar and the Friends of Pearl Fryar Topiary Garden nonprofit created a scholarship in 2008 to provide for local students traditionally ignored by higher education, specifically those with lower grades.

“He really focused his platform on speaking to the youth of the next generation because he felt that these are the kids that need the most help,” Gibson said. “You know, it’s hard [for an adult] to accept some hard truths or artistically be inspired by something like this, versus a child coming here and it’s like going to Disney World.”

Law recalled Fryar giving a tour to a group of students and gesturing at a sculpture of an upside-down flowerpot resembling a head. He reminding the students: “Don’t be a pothead.”

Waffle House, which the Fryars frequented almost daily, offered its support as well, donating $10,000 to his scholarship fund, annually. The Friends of Pearl Fryar Topiary Garden created a Waffle-House themed calendar as well, the sales benefitting the garden.

Christina Schnipke, the 25-year manager of Bishopville’s Waffle House, remembers brokering a deal with Pearl over the restaurant’s front hedges.

“He came over and I said, ‘You don’t have to pay for the Pearl Special, as long as you do my swirlies out front,’” Schnipke said.

The Pearl Special, Fryar’s usual meal, consists of wheat toast and one sunny-side-up egg “with a dot of grits,” as Schnipke put it. There’s even a sign highlighting the special menu item in Bishopville’s Waffle House.

As COVID-19 arrived in Bishopville, the Fryars stopped coming into Waffle House – but they still stopped by for takeout.

“He’d still take his car down to Waffle House and drive through the parking lot real slow and wave at the restaurant,” Schnipke said, “and we’d send him food every day.”

Even now, Fryar still takes his car out occasionally, waving at employees and customers.

Fryar’s story is a lengthy chain of events, an American story that isn’t over, Gibson said.

“He was able to relocate his family to Bishopville for the Coca-Cola plant, got denied, came out here built the house, had the opportunity to go into the nursery and seeing that guy trim the topiary at that exact time,” Gibson said. “It’s like fate – it all just happened for a reason, and it kind of took off from there.”

Fortune: The Arrival of Gibby Siz

On one of his usual visits to Fryar’s garden in March, Gibson noticed a group of people surveying the garden with landscaping equipment.

Immediately, he picked up a set of hedge clippers and began to assist. He didn’t know at the time, but the landscapers from Healy Horticulture had been contracted to repair Fryar’s garden by Jane Przybysz, director of the University of South Carolina’s McKissick Museum. The overhaul was funded by a $50,000 Central Carolina Community Foundation grant.

Gibson’s original plan had been to visit the garden the day prior, but avoided it due to rain.

“So if it didn’t rain, I would have came Sunday and I would have never met that crew. I would never have had an opportunity, there’s no way I would have found out,” Gibson said. He called the coincidence “divine intervention.”

The landscapers quickly noticed Gibson’s skill and informed Przybysz. Soon, she was in Fryar’s garden, speaking with Gibson at length about his history with the garden.

“Mike had spent considerable time, you know, learning what Pearl does and how he does it, right, and seeing Pearl as his mentor,” Przybysz said. “Mike clearly has a skill set that people deem to be high quality.”

After the head horticulturist on the project had to step down due to health issues, Gibson was the clear choice.

“I thought, ‘Okay, well, there’s Mike Gibson, he’s just kind of fallen from the sky,’ and so I worked to recruit Mike to relocate here for a year,” Przybysz said.

Gibson moved to Columbia in August, became the McKissick Museum’s topiary-artist-in-residence, and has spent most of his days since in Fryar’s topiary garden. Gibson has taken care to restore Fryar’s abstract creations to their original glory, without alterations.

As for future plans, Gibson fancies himself as Fryar’s protege. So does everyone else.

“The goal was always to see if we could make this a long-term thing,” said Przybysz. “I can’t help but be hopeful because I think Mike is a really great advocate for this project.”

An extension of Gibson’s year-long contract with the McKissick Museum is in the works, Przybysz said. In the meantime, Fryar’s garden and its legacy are one of a kind, and the man who has picked up the shears has found kinship with South Carolina’s topiary master.

“There’s not a lot of topiary artists in the world, especially when we talk about an African American topiary artist. So in searching, I found Pearl and myself, and that’s it,” Gibson said. “it’s kind of how I fell so much in love with his story, what he was doing, because there was nobody else like him and there’s nobody else like me.”

Mike Gibson stands where he proposed to his future wife in Pearl Fryar’s garden in 2018. Gibson has been clipping bushes since childhood, a skill he uses frequently as UofSC’s McKissick Museum’s topiary-artist-in-residence. Photos by Jack Bingham.

A pair of branches in Fryar’s garden coil around one another, helping support a larger structure. Over 40 years of work, Fryar ensured no detail went overlooked in his home garden.

Fryar and his wife, Metra, celebrate their 50th wedding anniversary at Bishopville’s Waffle House in 2016. During COVID-19, the restaurant delivered food to the Fryars. Photo courtesy of Christina Schnipke.

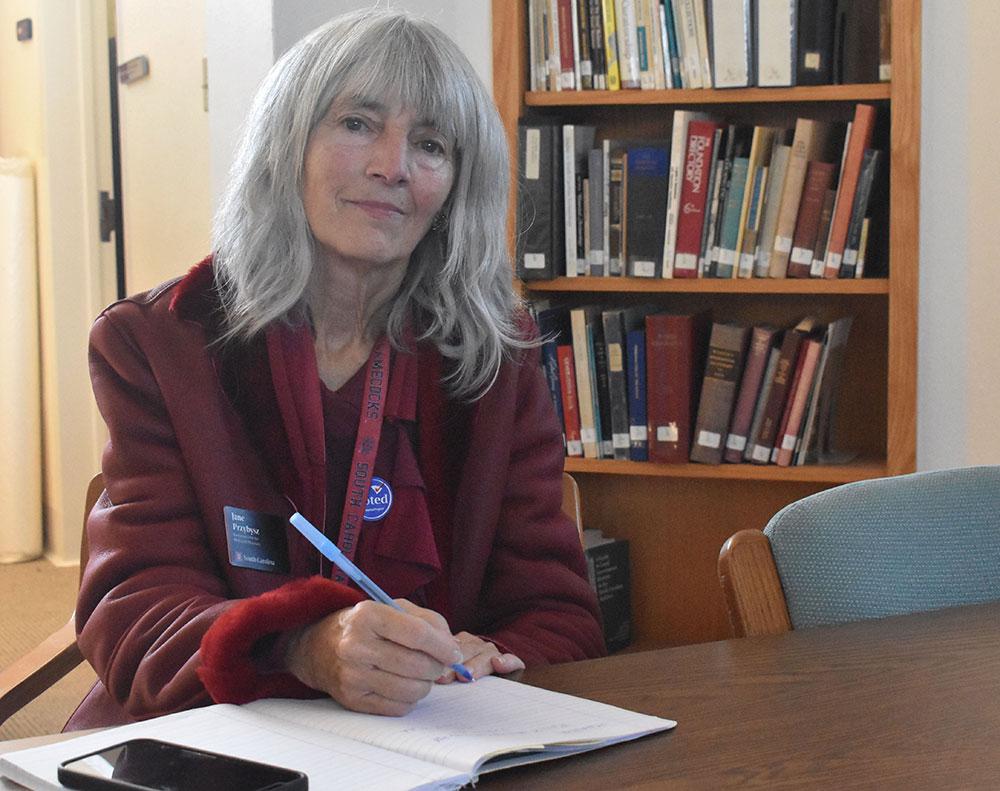

Jane Przybysz, pictured here in her top-floor office in UofSC’s McKissick Museum, hired Gibson to renovate Fryar’s garden with a grant from the Central Carolina Community Foundation. The Atlanta Botanical Garden and Healy Horticulture in Florence have assisted as well.