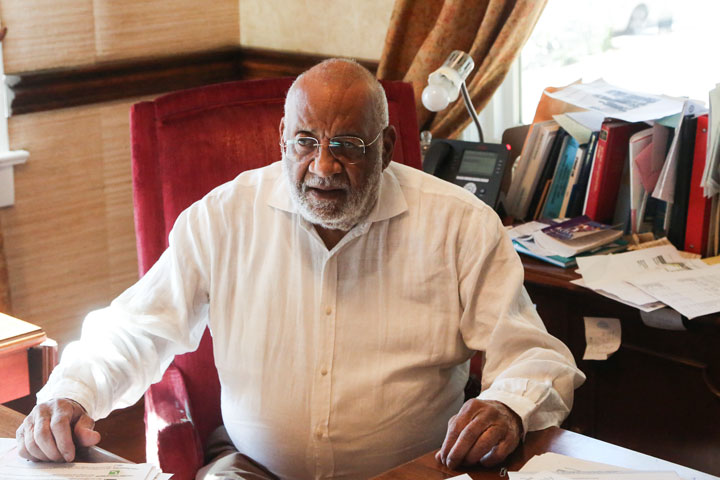

Moses Felder, 82, owner of Hill’s Barber Shop has cut hair for 55 years. His clients often come in and discuss news of the day and any problems the community is facing. Photos by Sebastian Lee

For more than 50 years, Moses Felder has clipped hair and shaved the heads of his neighbors at Hill’s Barber Shop. A few years ago, he started to notice something — more and more white people were moving into his Columbia neighborhood.

Patrons who occupy the chairs at the barber shop on the corner of Elmwood Avenue and Barhamville Road often discuss what’s happening in their neighborhood near Columbia’s downtown, and they too noticed the presence of more newcomers.

Some of the city’s historically Black areas, like the neighborhood Felder has lived in for decades, are at risk of losing their identity as demographics shift and the black population shrinks, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

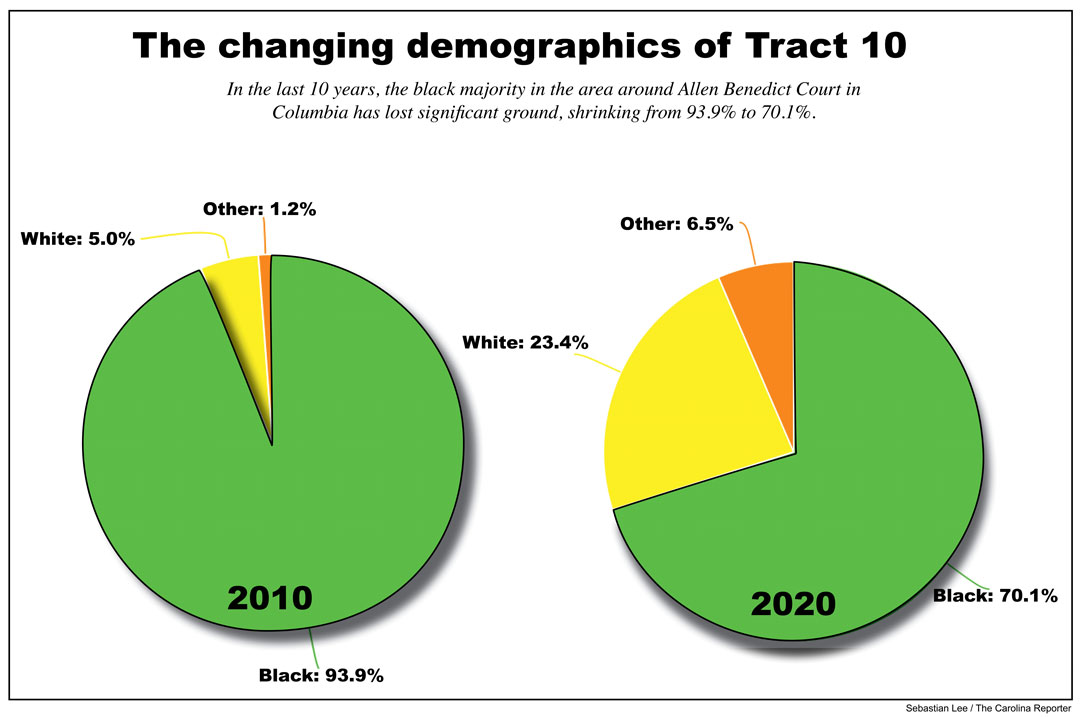

Between 2010 and 2020, the non-Hispanic Black population in census tract 10, an area bounded by Harden Street, Taylor Street, Two Notch Road and Chestnut Street, has dropped by 42%, from 3,304 to 1,870 people. In the same time, the non-Hispanic white population has increased by 261%, from 171 to 621.

In two of Columbia’s historically Black neighborhoods, Edgewood, where Felder lives, and Celia-Saxon, the Black majority has dropped from 93% percent to 70%.

“I think this community is going to change a lot,” Felder, 82, said. “I’m not against diversity, but I would like to see people who look like me.”

University of South Carolina academics who study the area say the data reflects larger trends in American cities. That includes an out-migration of Black residents to the suburbs and an inward movement of affluent whites who seek to gentrify established neighborhoods. Gentrification is the movement of wealthier people into poorer, urban neighborhoods, dislocating the former occupants.

There’s been a trend of Black residents migrating out of the city for over a century, according to Bobby Donaldson, an African American history professor at UofSC. Donaldson is an expert on Black life in downtown Columbia and the neighborhoods surrounding it.

Each successive wave of urban development has pushed the Black community farther and farther away from the city center, according to Donaldson.

“Would a middle-class white family want to live down the street from a working-class Black family living in a rental?” Donaldson asked. “That is rarely the case.”

Hemphill Pride II, 86, who has worked as an attorney and civil rights activist in Columbia for nearly 60 years, said that the changing demographics are caused by gentrification.

“The future of that area is going to be whiter and whiter and whiter,” Pride said.

For the past 80 years, two brick public housing projects, Saxon Homes and Allen Benedict Court, dominated the area around Celia-Saxon and Edgewood. As the projects aged and fell into disrepair, the prospects for residents also seemed to decline as more prosperous residents left the area.

Saxon Homes, which opened in the 1950s, provided 400 low-income apartments. It was demolished in 2000 and replaced with Upper and Lower Celia-Saxon, which provided 59 cottage-style homes with one-to-three bedrooms.

Allen Benedict Court on Harden Street was constructed in 1940 and housed more than 400 residents in 244 low-income housing units. After a carbon monoxide leak caused two deaths in 2019, it was demolished earlier this year.

“That (Allen Benedict) was like the last of the Mohicans,” Pride said. “I don’t even go that direction, because I don’t want to see it.”

In the lot where Allen Benedict Court was once located, all that remains is the rubble from its demolition.

With the loss of these housing complexes, more than 800 mostly Black residents, were displaced, many moving out of the downtown area that anchored black life in Columbia for decades.

That worries Todd Shaw, a UofSC political science professor and expert on African American politics, urban politics and public policy, who sees the out-migration of poorer residents as an affront to a livable city.

“If you have to fundamentally displace working-class families or minority families from homes in order to redevelop an area, that’s not redevelopment in a balanced or even progressive direction,” Shaw said, “That’s dislocation on some level.”

The changing demographics of the area reflect a larger, state-wide trend. In the last 10 years, the city of Columbia has lost 3.6% of its Black population and saw a 3.7% increase in its white population.

Other cities across the state show similar trends, the most notable of which is Charleston. Between 2010 and 2020 the city of Charleston’s Black population decreased by 16% while its white population increased by 31%, according to a Carolina News and Reporter analysis of census data.

“These are the things that are being discussed in the barbershop,” Felder said. “We saw what happened in other cities, and people start discussing that the same thing is going to happen in this area.”

Felder sees the recent mayoral race and the election of a white mayor as a reflection of the changing demographics of Columbia. Donaldson and Pride concur.

Longtime city councilman Daniel Rickenmann was elected mayor after a runoff against fellow councilwoman Tamika Isaac Devine, who would have been the first Black woman to serve as Columbia’s mayor if elected.

Outgoing mayor Steve Benjamin, the city’s first Black elected mayor, has championed the BullStreet District project which will transform the old state mental hospital complex into a joint neighborhood and shopping area that is expected to draw more affluent people downtown. He has said the project will benefit all of Columbia and improve the economic prospects for residents in North Columbia, which is predominantly African American.

“It’s a plan in all the cities to get white folks back in, to dominate the cities,” Felder said. “Some people think that with the money being put into BullStreet, that’s going to push this way.”

After schools were integrated in the 1960s, many white families exited city centers for the suburbs. That “white flight” left Black residents in the cities. That trend has reversed with more and more white people moving back into cities, acquiring solid housing stock and then embarking on expensive renovation projects. These projects tend to raise the property value of the area making it much harder for the lower income residents to remain in their area.

“I saw white people coming back to the city. They were coming back in large numbers,” Pride said, “(I thought) What’s gonna happen to my people?”

Hill’s Barber Shop is located on the corner of Barhamville Road and Elmwood Avenue in the center of census tract 10.

Hemphill Pride, 86, said he fought “tooth and nail” to stop the demolition of Allen Benedict Court.

Upper and Lower Celia Saxon was built in 2001 on the site of what was once Saxon Homes.