The Dutch Fork Magistrate Court is one of 11 magistrate courts in Richland County.

Local landlord Vann Mullis attends almost every eviction hearing date at the Dutch Fork Magistrate Court.

Judge Mel Maurer, who has been at the Dutch Fork Magistrate for 35 years, used to be mayor of Blythewood. His court oversees thousands of cases a year, although only a small percentage actually go to a hearing.

Part 1 of a two-part series

The room, with its beige walls and rows of silent people clutching folders, feels like a study hall. Perhaps detention.

One woman in a faded dress that isn’t zipped the last inch in the back methodically takes everything out of a battered green folder, looks over page after page of rent notices and medical records, and then puts them back in the folder, perfectly squared up.

The docket, posted at the back of the courtroom, hasn’t been updated and shows a list of criminal cases instead of the 50 or so civil disputes about to be heard.

No one looks at each other, let alone breaks the silence with spoken word. The only sound is someone’s phone inexplicably gurgling like a water cooler.

In the back row a young woman who moved to Columbia from Allendale a year ago to live with her boyfriend and two nephews waits. She’s the only one working in the household. She just started a new job, but hasn’t yet received her first paycheck. She doesn’t want her name or photo used, she says, because this isn’t like her.

“I don’t get evicted,” she says.

“Well you’re about to,” her stepmom retorts.

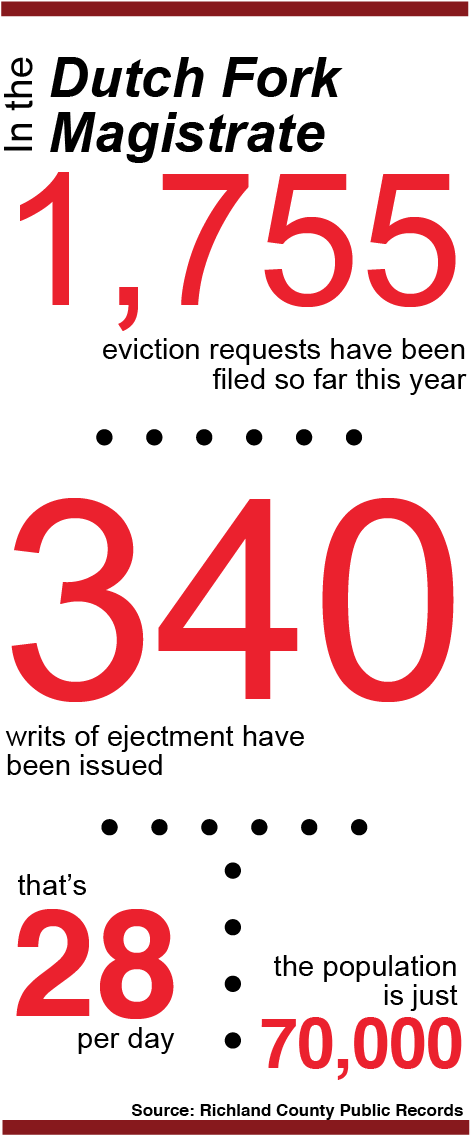

More than 1,700 eviction cases – 1,755 to be exact – have been filed in the Dutch Fork Magistrate Court, one of 11 magistrate courts in Richland County, South Carolina, since Jan. 1 of this year.

Judge Mel Maurer, who has been on the bench since 1982, didn’t end up hearing the Allendale woman’s case — she came to a binding agreement with her landlord to pay the missing rent within eight weeks. Three others weren’t as fortunate that day, though, and will soon see their belongings on the street. They didn’t show up to court.

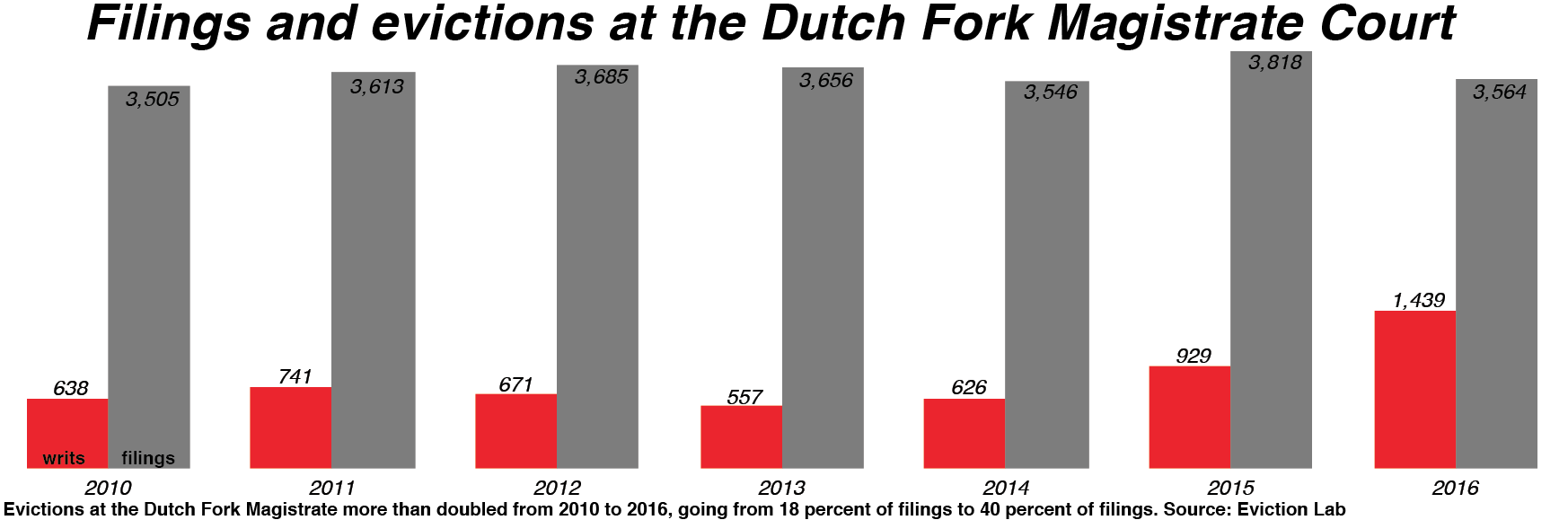

A lack of public knowledge about the eviction process and low court fees create a state where filing for eviction becomes a common rent-collection tactic, contributing to high eviction rates across the state.

South Carolina leads the country in evictions per household, according to recently released data collected by Princeton University researchers and non-profits. While the data isn’t comprehensive — three states have no data at all, and selected counties are missing — the study shows an epidemic of evictions across the state. Columbia ranks eighth among large cities, and the Saint Andrews suburb ranks first for mid-size cities. And the problem is only getting worse.

“Leads the nation, huh? I’m not surprised,” local landlord Vann Mullis said. “I’d imagine I’m right up there with them; I’m in court about, well, two times a month. My friend was a lawyer and I joked that I spent more time in court than he did.”

Mullis, 72 and retired, rents out 28 low-rent properties. Since the start of 2016, he’s filed 104 eviction cases in Maurer’s court. The vast majority were settled. The tenants paid or came to an agreement in court.

“I get a lot of reasons why they can’t pay,” Mullis said. “And I did an agreement with one of my people today, and I probably won’t get the money. You hate to turn people out but I can’t afford to not do it. Because when one of them sees what somebody’s gotten away with, then they try it too.”

Housing lawyer Adam Protheroe with South Carolina Legal Services defends low-income South Carolinians in cases where they aren’t guaranteed representation by the state. But even South Carolina Legal Services can only handle a few hundred cases each year. In 2016, they closed 458 eviction cases. That same year, 80,000 eviction requests across the state were filed.

“Despite the fact that we are the largest law firm that represents tenants, we see still such a small fraction of the cases that are filed in this state,” Protheroe said. “We’d like to see more, but we do as many as we can.”

While Legal Services works in the courtroom, Appleseed Legal Justice Center in Columbia works at the policy level to fight for tenants rights.

“There’s an unfairness implicit in like the court system if you don’t have an attorney and the other person does,” said Ashley Thomas, Appleseeds’s director of strategic initiatives. “If you’re not paying your rent, you probably don’t have the money for an attorney.”

So far this year, not a single resident has appealed an eviction ruling in Richland County.

“I want people to assert their rights more, but I understand that’s maybe not everyone’s priority,” Thomas said. “Because if you’re dealing with trying to get your children fed, the last thing you’re thinking about is being a champion for the cause.”

So thousands face eviction without consultation, unaware of protections and possible defenses. The harsh reality, though, is that non-payment of rent is one of the hardest grounds for tenants to fight.

“[The law] really eliminates even having a reason,” said Donald Wood, the executive director of the South Carolina Apartment Association.

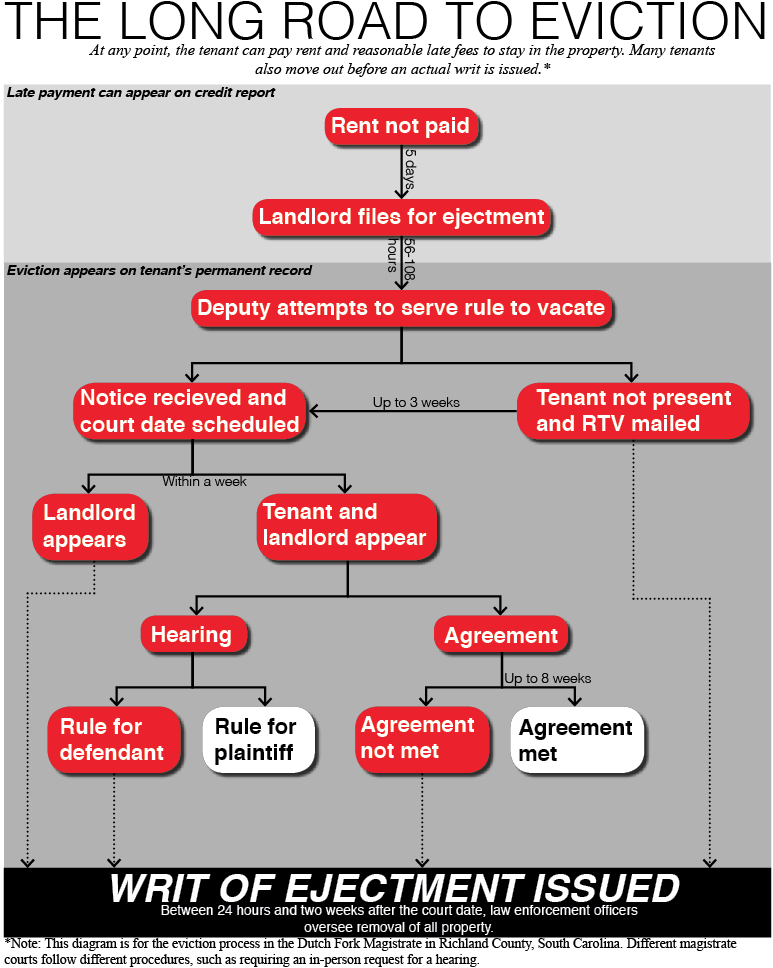

The S.C. Residential Landlord and Tenant Act, a 1986 piece of legislation that established tenant rights for the first time, also set out the legal eviction process. Tenants can be evicted for different reasons, like breaking the law or violating the lease agreement, but with non-payment of rent the process is fairly cut and dry. If the rent is late, the landlord almost always wins. The most that tenants can hope for is a few extra days to remove their belongings.

The law also says that landlords can only pursue evictions through the court system, which requires providing notices and set amounts of time for the tenant to respond.

Mullis said it takes him eight weeks to get a tenant out who isn’t leaving on their own.

“That is bad on the people that are gonna catch up,” he said. “You can’t give them any leeway because of the people that really abuse the system.”

He suggests shortening the time it takes for an eviction to process, especially the mandated 21 days to wait for a mailed notice if tenants don’t answer the door to police.

While South Carolina is about average in eviction process length, Protheroe said, filing costs are unusually low. A normal filing costs $40, with an extra $10 for an officer to serve the writ of ejectment and remove the tenant. Just across the border in North Carolina, it can cost up to $200 to evict.

When the cost is so low, Thomas said, eviction filing can become a rent collection mechanism.

Some apartment complexes file up to 50 eviction requests a month, then settle or come to agreements in almost all.

“The goal is to resolve it with the tenant and not have it reach that point,” Wood said. “Their goal as managers is to make sure that property is maintained and there is someone actually paying rent.”

Wood disputes the Princeton University findings for South Carolina, saying that it’s skewed by rent-collection eviction filings that don’t result in actual evictions.

Any eviction filing, though, shows up in public records and can make it harder to find new housing, especially for tenants who are consistently late and wrack up numerous filings.

There are fewer people at the Dutch Fork Magistrate Court the next week, and only one person requests to go before the judge.

She stopped paying rent when she noticed mold growing in the apartment. In South Carolina, tenants can void their lease if they demand repairs necessary for quality of life and the repairs aren’t made within two weeks. Her special needs child has respiratory problems that were aggravated by the mold, she said. But because she hadn’t demanded the repairs, the landlord was able to file for eviction.

Judge Maurer helped the parties come to an agreement — she would be out of the property within five days and the lease would be voided, and not show up on her record.

But she’s at risk of losing Salvation Army rent assistance — it requires having an address, something she won’t have while temporarily staying with her mother.

“Without something coming to intervene, it’s really hard to break out of systemic poverty,” Thomas, the Appleseed advocate, said. “So having an eviction, or having housing issues of any sort of legal issues is just going to set you back further and further.”