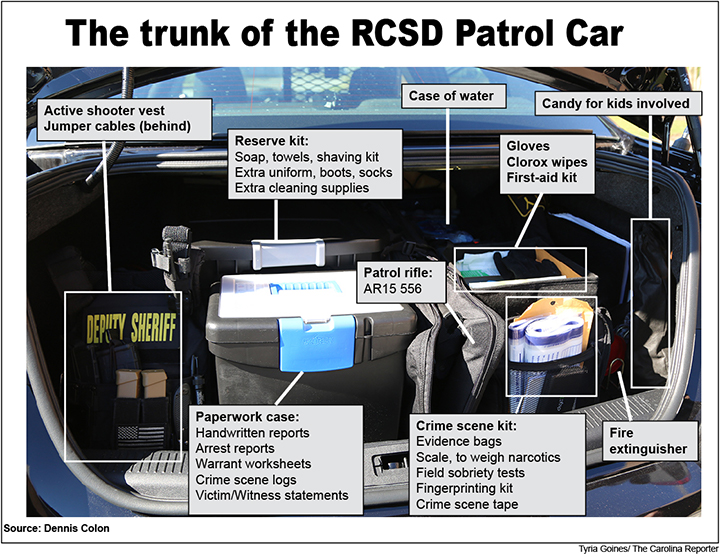

“The tools that we have at our disposal now, have really saved a lot of peoples’ lives in the long run. So, it would be nearly impossible, I think, to do this job nowadays without the tools that we have, without technology on our side,” said Major Harry Polis, RCSD.

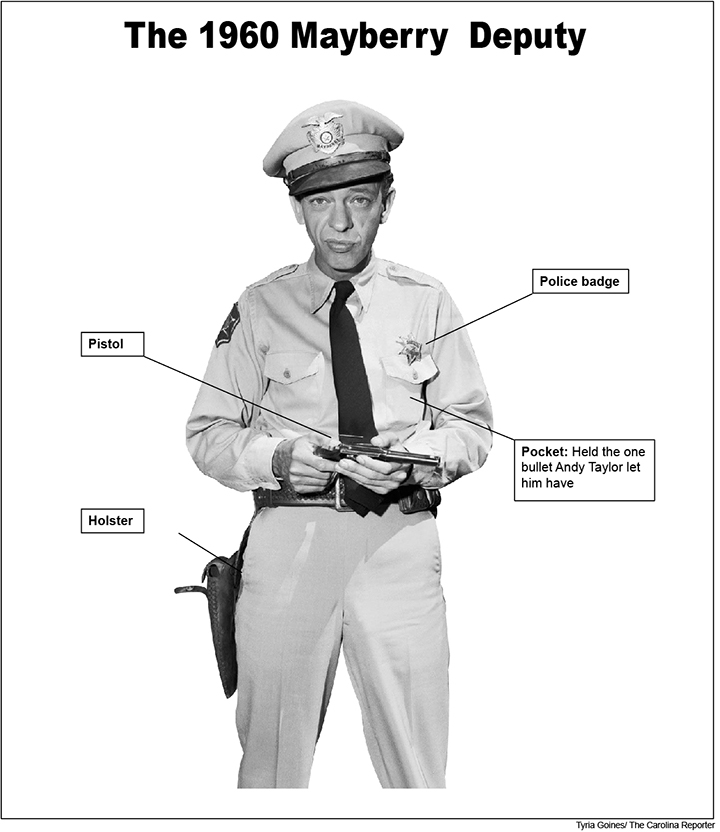

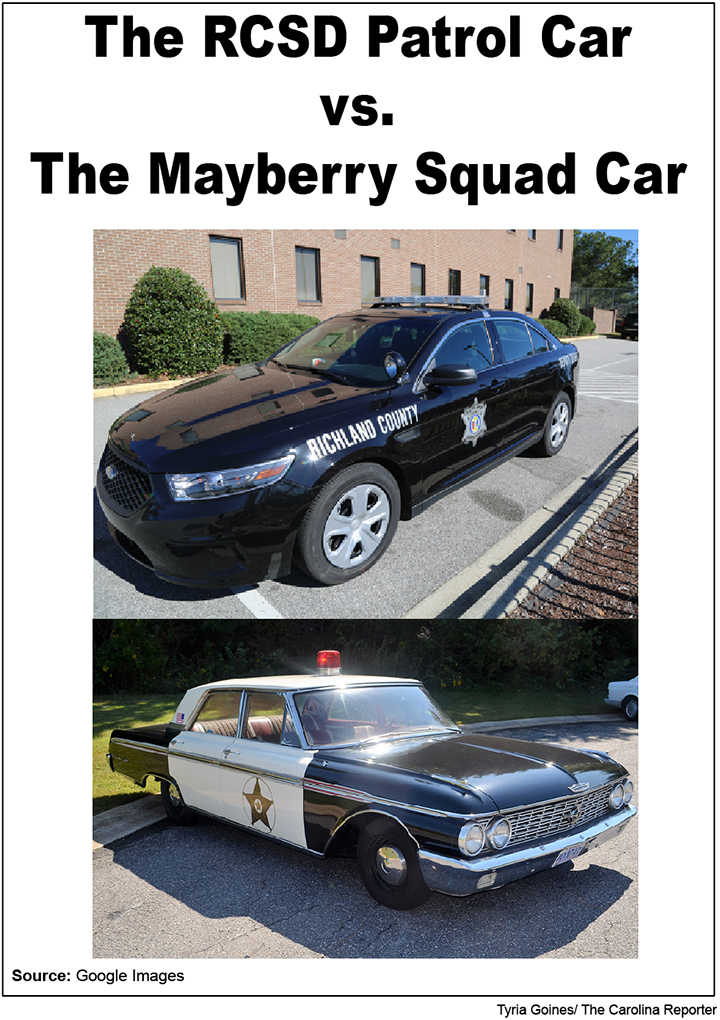

The classic 1960s television duo Andy Taylor and Barney Fife, the sheriff and deputy of Mayberry, North Carolina, gave the public a comedic spin on law enforcement. With the one bullet Andy restricted for Barney, an old radio, and a police car with one siren, the pair protected their small town of Mayberry on countless half-hour episodes of The Andy Griffith Show.

Today, police still rely on those basic 20th century tools, but technology has transformed law enforcement, from the use of DNA to sophisticated fingerprinting to surveillance and body cameras.

Since Maj. Harry Polis Jr. came to the Richland County Sheriff’s Department 16 years ago, he has had to undergo additional training to use the latest technological additions to his department, like the Mobile Data Terminal or MDT and tasers, both introduced in the early 2000s.

Probably the most dramatic tool aimed at holding police departments accountable was the introduction of body cameras in 2014. Body cameras have recorded thousands of police encounters, some mundane, others dramatic.

In Chicago last fall, Jemel Roberson, a 26-year-old security guard, was fatally shot by officer Ian Covey. Roberson was detaining a suspected gunman who opened fire at the bar where he worked. Body cam footage was used to reveal the identity of the officer, nearly three months after the shooting occurred.

On March 18, 2018, Stephon Clark was shot after police received a report of someone breaking into cars. The Sacramento officers who responded to the scene, Terrance Mercadal and Jared Robinet, opened fire after Clark appeared to be holding a handgun. Body cam footage later revealed he was holding an iPhone, not a weapon, although no charges were filed against the officers.

Body cams evidence has been used increasingly in investigating shootings. A nationwide survey of 67 major cities and 76 major counties, funded by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, found that 95% of police departments either have already or intend to implement a body cam program.

“There was a cry for accountability,” Polis said. “And the goods cops, we wanted them because we knew that it would help us. It would give people the opportunity to see firsthand what we were experiencing from our point of view. That’s something that unless you do this job, you can never understand.”

A 2015 law required all law enforcement agencies in South Carolina to use body-worn cameras. RCSD partnered with a company called Axon, which also supplies the department’s tasers.

The cameras are automatically turned on and begin recording when a deputy uses their taser. With this equipment working in conjunction, deputies do not have to remember to manually turn on their cameras. Some deputies even have a device where the camera is turned on once their pistol is removed from their holster.

“They’ve gotten very user-friendly. Just in the five to six years of having them, it’s been a huge improvement. We’ve seen a reduction of complaints against deputies, and we’ve seen a reduction of use-of-force incidents,” Polis said. “Citizens know when we get out of the car, we’re recording and we’re fine with that. Because we’re not doing anything wrong, we don’t have anything to hide.”

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice awarded over $23 million in funding to support the implementation of body cam programs throughout the country. And while legislation mandates that body cams are required in South Carolina, to Polis, the legislature often fails to provide all of the funding needed acquire it.

“It’s a very expensive piece of equipment. But when a situation rises and you can go back and play the tape and say this is why our deputy had to use deadly force and you can see from your point of view what that deputy or police officer was experiencing, that’s invaluable. You can’t put a price tag on that,” Polis said.

Dave Williams, a retired police major and instructor at Anderson University, remembers when Greenville County Sheriff’s Department started using in-car cameras in the mid-90s and the complications with funding and keeping them operational. He believes that technology is beneficial, but the rapid development and constant changes can be a problem for cash-strapped police departments.

“Technology has been instrumental over the years and helped in a lot of different ways,” Williams said. “We were one of the first in the state to have in-car cameras. There was a little resistance to it by the men. They just weren’t sure about the new technology. But that got to be just part of doing their job. I think everyone is a little apprehensive about a new technology.”

As he studied police techniques, Polis learned that back in the 1950s and 1960s, community policing in departments was virtually non-existent. Officers were not taught de-escalation methods, but rather given a gun and handcuffs and told to “go to work.” The only other tool they had aside from on their belt was their mouth.

“And I think often times we underestimate the power of what we say. I can de-escalate a situation just by talking to somebody,” Polis said. “Trying to talk to them, understand someone’s point of view. We’ve come a long way in law enforcement as far as how we train. We’re really taught about de-escalation, talking to people, not at people.”

A public skeptical about police shootings is also clamoring for accountability among the officers. Polis believes the cameras are a benefit for “the good deputies,” but the most important equipment an officer can have is not located on their belt.

“I would say the most used piece of daily equipment is your mind. You have to think about what you’re doing, when you come out here,” Polis said. “You can’t immediately resort to the tools on your tool belt to solve a problem. I really think the piece of equipment that is the most important thing you use everyday is your brain. Think about what you do before you do it.”

Andy and Barney would probably be amazed with the advancements in law enforcement technology has advanced. Andy would probably still only give Barney one bullet, just in case.