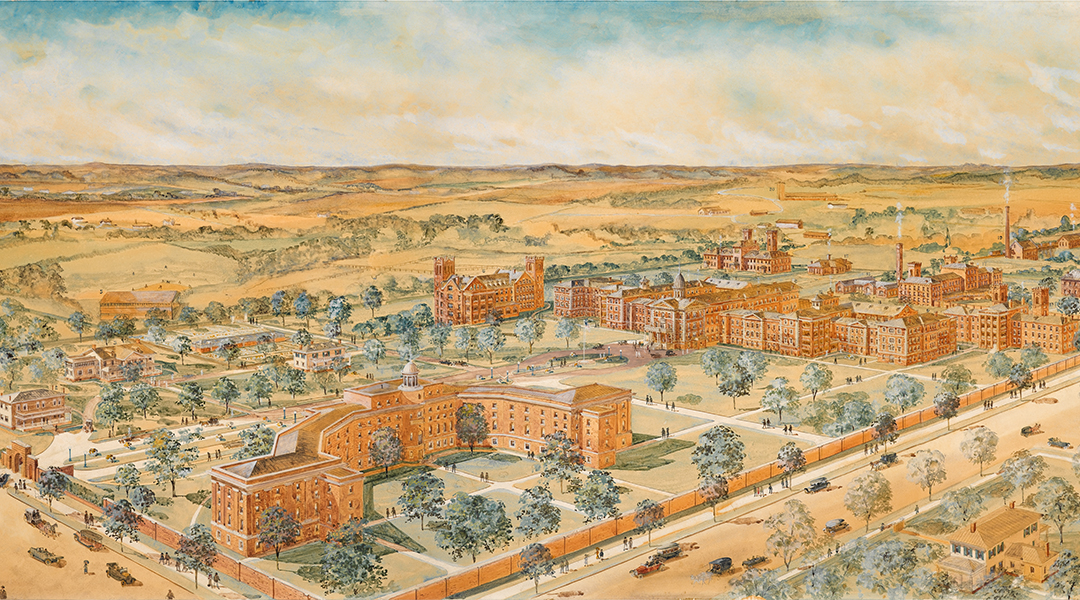

A bird’s-eye view of South Carolina State Hospital circa 1916. Note baseball field at middle left, in close proximity to the modern-day site of Spirit Communications Park.

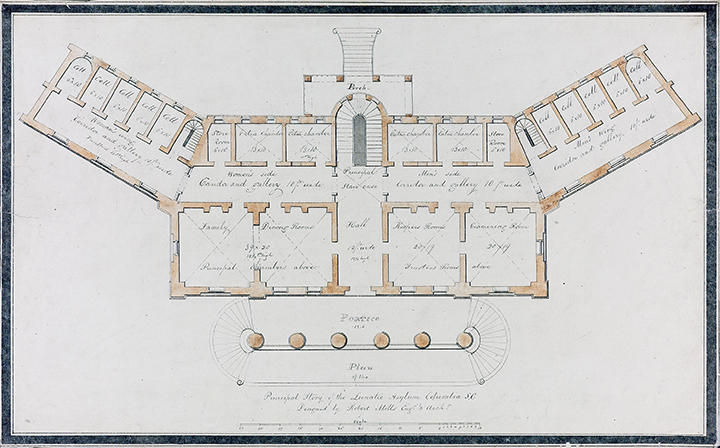

Floor plan for the first story of the Mills Building. South Carolina State Hospital’s original building was designed by famous architect Robert Mills in the early 1820s.

Dr. James L. Thompson served as a physician at South Carolina State Hospital from 1881 through his death in 1940. His memoirs, left to family, now reside in Thomas Cooper Library.

South Carolina Gov. Donald Russell poses with state lawmakers after signing a law giving the S.C. Mental Health Commission full state agency status on March 26, 1964.

Within hours of the Feb. 14 mass shooting at Stoneman Douglas High in Parkland, Florida, Americans from Fort Lauderdale to Fort Jackson suspected there were warning signs.

Within days, officials detailed a litany of troubling police, counseling and school encounters with the 19-year-old shooter, Nikolas Cruz. A month after Cruz shot and killed 14 students and three faculty, the Associated Press uncovered documents that stated school officials and law enforcement wanted him committed involuntarily to a mental health facility as far back as September 2016.

As students, parents and gun control advocates march for gun reform, there are calls for more effective ways to identify potential shooters. But balancing the rights of the troubled individual—who may or may not commit a crime – against public safety has vexed Americans since the founding of the Republic.

Florida Gov. Rick Scott warned that society “should not have disconnected youth wandering around in our communities,” but cautioned that mental health reform should include only “the right kind of interventions.”

In South Carolina, “the way we look at it is… we’re not out there looking for people who are prone to violence, we’re out there looking for people who may need treatment,” said Mark Binkley, deputy director for administrative services of the S. C. Department of Mental Health. Most of those undergoing treatment by the Department either self-refer or are referred by their families.

Myths and mental illness

For the better part of the 19th and 20th centuries, institutionalization, not intervention, characterized treatment those deemed mentally unbalanced. The South Carolina State Hospital, built in 1822 on Columbia’s Bull Street, became an asylum of such notoriety that to say you were at “Bull Street” captured the image in the public mind and in Carolina vernacular. Its time came and went with the introduction of antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs and localized mental health service.

Today Bull Street is merely a memory; the development of community care in the 1970s and 1980s led to patients being discharged to programs around the state in the 1990s. A full section of the SCDMH mission statement now outlines the department’s dedication to local care.

“It’s a whole new world compared to the ‘60s and ‘70s,” Binkley said.

Binkley said the emphasis on outpatient care began to grow in the 1950s when French researchers discovered the anti-psychotic chlorpromazine, known in the United States under its trade name, Thorazine. From there, lawsuits over the conditions at state hospitals closed many.

“The idea that state hospitals were just full of all these people with mental illnesses is one of the great myths,” Binkley said. “State hospitals were basically one-size-fits-all for anybody that society couldn’t care for adequately on the outside.”

State hospitals were often used even for nursing care, a trend that changed with the introduction of Medicaid-funded nursing homes in the 1960s.

Though no patients reside there today, some of the State Hospital campus still stands in the shadow of Spirit Communications Park, its days numbered in step with the trendy BullStreet District. Though most who saw the inside of the facility at its peak in the early-mid-20th century are long gone, many of their stories still stand today.

Remembering the dark days of Bull Street

The memoirs of Dr. James L. Thompson, a physician at the State Hospital from 1881 until his death in September 1940, paint a vivid picture of the everyday duties of State Hospital medical staff around the turn of the 20th century.

Thompson recounted a patient who declared the 1886 East Coast earthquake, which shook the hospital and had its epicenter near Charleston, the “devilment” of one of the physicians. Another patient wrote checks for thousands of dollars despite having no money to her name. When informed of this fact by the doctors, the patient insisted “‘my shipload of money will arrive today.’”

In his time, Thompson saw numerous cases of typhoid fever and measles and found that the acute skin infection erysipelas was common in the spring. An 1897 smallpox outbreak affected 75-80 people within the State Hospital walls, he estimated.

Thompson referred to both “patients” and “inmates” in the document, now housed in USC’s Thomas Cooper Library, and wrote in a manner that can be alternately humorous and dark. He describes the food as “substantial” but not necessarily well-made, the bedding as cheap, the funds for embalming the deceased as nonexistent.

Many of the accounts he wrote feature patients he describes as manic depressive, epileptic, or simply depressed. Thompson wrote little about patients acting violently.

Industrialization and mental illness

At least one clinical director of the hospital suggested industrialization was to blame for rising crime and disaffected citizens. In 1925, Eugene Leroy Horger wrote a paper on the topic, “Mental Disorders and Their Relationship to Crime,” framed his data around an increase in urban crime following World War I and asserted that the rapid rise of industrialism naturally left behind individuals that could not keep up with society’s changes, leaving crime a solitary option.

As evidence, he cited National Committee for Mental Hygiene study that found 64.2% of S.C. State Prison inmates were “abnormal in their mental makeup” and that 40% of that portion were repeat offenders.

“The inability of the human mechanism to adapt itself to the enormously rapid changes in the modern occidental environment has had a tremendous influence upon the creation of the misfit, modern industrialism with numerous inventions and discoveries, has rapidly changed the environment in which we have to live,” Horger wrote. “It is an artificial, an uncongenial world, and in the effort to adapt our nervous machinery to sufficient rapidity, many of the weak and frail are falling by the wayside, only to find themselves confined in our prisons or other state institutions.”

To combat the problem early, Horger proposed separating the 2.8% of white schoolchildren and 4.2% of black schoolchildren deemed “mental defectives” from other students in public schools. He also cautioned that these segments of the school population could become a “source of supply” for the state court system.

Horger also warned readers against a lack of sympathy for discharged inmates: “His record invariably accompanies him in an effort to secure some gainly occupation, hence he fails to receive any help or encouragement from the society which has, more or less, been responsible for what he is.”

Modern medicine and outpatient care

Today, according to Binkley, involuntary patients comprise all of the 300 admissions each year at Harris Psychiatric Hospital in Anderson and 800 at Bryan Psychiatric Hospital in Columbia, both SCDMH-run. A further 60 to 70 percent of the 1,500 individuals admitted to Morris Village Alcohol and Drug Addiction Treatment Center in Columbia are taken in involuntarily, he said.

By comparison, the State Hospital’s population exploded under Thompson’s tenure, from 490 upon his arrival in 1881 to 5,300 at his death in 1940. However, Binkley said SCDMH does not have good data on the number of patients admitted to private or community psychiatric hospitals, such as Three Rivers Center or the Behavioral Care program at Palmetto Health.

But regardless of the number of people in the state’s care, a thorough search of the state’s citizenry for potential school shooters is not the SCDMH goal, Binkley insists.

Instead, SCDMH is currently seeking the expansion of current outpatient programs in place of institutionalization.

In 1987, Charleston Dorchester Mental Health Center founded the state’s first Mobile Crisis team to work with Charleston law enforcement and EMS. One of the program’s greatest advantages, Binkley said, is that therapists with the Mobile Crisis team are available on weekends and late at night – whenever they are needed so individuals can get treatment instead of going to jail.

Binkley said new funding is being provided to bring Mobile Crisis teams to rest of the state under the program name Community Crisis Response and Intervention. In March, Greenville Online reported that the program should be operational in Greenville this summer.

Another program seeing expansion is SCDMH therapists in public schools – but again, Binkley said the program is not simply a watchdog for high school students who pick up a weapon. Nor does he see Gov. Scott’s “disconnected youth” as a blanket profile of school shooters.

“Currently, I don’t think disconnection is a basis for thinking someone is going to be violent, nor do I think disconnection is a basis for involuntary treatment,” Binkley said.

SCDMH has embedded therapists in 620 public schools around in South Carolina – about half. At the SCDMH budget hearing in January, the state House Ways and Means Committee approved of $500,000 in new funding to embed a further 20 counselors in public schools.

“Those therapists are not there looking for people who are violent,” Binkley said. “Those therapists are there as a resource to the students, to the teachers who see a student who may be one of these disconnected youth.”

Binkley admitted that the program “probably” helps prevent tragedies but mostly helps students form relationships. Students who take part in the program report better grades and stronger relationships with family after treatment, he said.

“It’s not designed to be a solution to violence,” Binkley said. “But we think that obviously when you help people with their own problems, you’re gonna obviously reach some people who I guess without that intervention could have gone on to commit some tragedy.”

But more serious than the specter of school in violence, Binkley said, is the rate of suicide among young people around the state.

According to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, suicide is the second leading cause of death among residents age 10-14 and third leading cause of death among residents age 15-34. Twice as many people around the state die by their own hand than by homicide each year, and one South Carolinian takes their life every 12 hours on average.

“It’s really a much bigger problem,” Binkley said. “I know school shootings grab the headlines – but a much bigger problem when you’re talking about school-age kids is the rate of depression and the rate of suicide.”

In conjunction with community mental health centers and universities around South Carolina, SCDMH’s Youth Suicide Prevention Initiative is now in its third year. And not a moment too soon given that, in 2015, CDC’s Youth Risk Behavioral Survey found that 11 percent of South Carolina respondents had attempted suicide in the past year. The national average for respondents stood at 8.6 percent.

“I think possibly the good [thing] that’ll come out of [Parkland] is to make people more aware of the resources,” Binkley said.