A preacher walks into a bar.

This is not the setup of a joke, but the start of Jody Ratcliffe’s monthly Sunday worship service at New Brookland Tavern in West Columbia.

Ratcliffe, a Southern Baptist pastor, started The Church at West Vista after his then-senior pastor at Holland Avenue Baptist Church asked him to think of ways to save their dying church.

After a few years of deliberation, Ratcliffe decided to plant an entirely new church, one based on the “blueprint church” from the Book of Acts in the Christian Bible’s New Testament.

“The early church, they were a very relational church, they met in small groups in homes,” Ratcliffe said.

Much like the biblical Peter, Ratcliffe leads a churchless congregation. Divided into three “house church” groups, members meet with their house churches weekly. Once a month, the entire congregation comes together for worship at New Brookland Tavern.

Ratcliffe, who received financial help from the S.C. Southern Baptist Convention to create West Vista, has managed to capture the most elusive age group for mainline churches: millennials.

According to the Barna Group, a California-based market research firm that studies American religion and culture, 61 percent of millennials, ages 20-34, said they “find God elsewhere” as a reason for not attending traditional church services.

Jordan Grimmesey, a 21-year-old student and member of the Presbyterian Church (USA) of the U.S.A. grew up in a small, tight-knit congregation in Atlanta, Georgia. She said although her faith has “shifted a little bit more spiritual,” she believes her church fostered her current religious practices.

The desire for the spiritual over the ecclesiastical keeps many young adults from attending church.

USC Lutheran campus pastor Michele Fischer said she sees this trend of separation of God and church in young people.

“The need for God is innate, it is part of who we are,” Fischer said. “We need something divine, something spiritual… some people haven’t found that in the organized church and they’ve left the organized church.”

For many, she said, “The mainstream church feels inauthentic.”

“Authentic Community,” may be a modern buzzword for hip churches to adopt, but it carries weight with young adults and teenagers – 78 percent of millennials prefer “community” over “privacy” in the church, according to the Barna Group.

In the age of the internet, young Christians want face-to-face, interpersonal relationships with their churches.

But millennials’ preference for an experiential faith over a theological one flies in the face of the authenticity the same age group is searching for, Fischer said.

“The only thing that’s going to be authentic is a faith that is deep,” Fischer said.

That depth of faith can only be achieved through a community, most usually a congregation, Erik Kimrey said. Kimrey is the head football coach at Hammond School, where he also teaches philosophy of religion.

About a decade ago Kimrey and a few friends started Theology on Tap, a discussion group where people from any walk of life can come and talk “big, scary questions” with a beer in hand.

Kimrey said the program, which meets at Indah Coffee Co. once a month, “helps people realize there is a huge diversity of views inside the church and outside the church.” Kimrey said Indah Coffee provides a setting that feels more comfortable than “a rigid setting like a church,” where some may feel uncomfortable to voice concerns or doubts about topics like “Where do we come from? Why are we here?”

According to the same Barna group study, millennials tend to feel more at ease in familiar settings like a coffee shop or a bar instead of a sanctuary. But, Kimrey said Theology on Tap isn’t a replacement for church, but a supplement.

“I wouldn’t suggest coming to Theology on Tap to replace church,” he said. “It’ll never replace authentic community, wherever you find that.”

One reason young people feel uncomfortable in traditional churches is the “perceived intolerances” many believe mainstream Christian churches harbor.

Grimmesey said she chooses to “very much separate my separate spiritual religious experience from other denominations of my own religion” because of these perceived intolerances, some of which include homosexuality and political party affiliations. Grimmesey’s church is more theologically liberal than most denominations, homosexuals can be ordained and married in the church.

Deja Warnock, a 21-year-old member of Right Directional Church International, also believes a church congregation is the only way to foster a deep faith, but she doesn’t think the church is as welcoming as they could be. Warnock said congregations need to “open their doors” to those who may be apprehensive since it is the mission of the church to welcome without judgement.

“God says ‘come as you are,’” she said.

Warnock works for Your Life, RDCI’s millennial fellowship group, which has over 30 members. But for the past 20 years, millennial dropout rates have been rising in churches. According to separate Gallup polls, the number of Americans who attend religious services weekly has declined from 42 percent in 2008 to 38 percent in 2017.

“It’s at least an American phenomenon, if not worldwide,” Fischer said of the dropout problem.

Like most things in organized religion, the dropout problem was not caused by a simple, singular issue, but a composite of generational differences, changing perceptions and a rapidly changing culture.

One factor is time.

“The Greatest Generation is dying,” Ratcliffe said. “And that was your greatest boost of numbers from 1960 to 1980.”

The Greatest Generation includes people born before 1928. In 2017, less than 3 million were left in the U.S.

“They came back from the war, huge revival. I mean, they’d seen hell,” Ratcliffe said of the generation who made up most of America’s armed forces during the Second World War.

“They came back and said, ‘God’s real.’”

During the mid-20th century the church relied on this age group, who were also bringing their children and grandchildren every Sunday, to fund and fill their ministries.

Demographics have changed in churches since the eighties, but church programming has not.

“The church has a long memory,” Fischer said. “They’re slow to change.”

Ratcliffe’s church is attractive to millennials because he doesn’t rely on long-term programming or an accomplished organ player to draw people into his congregation.

“Our attraction would be the interpersonal relationships,” Ratcliffe said.

Ratcliffe, the pastor of the house churches, said millennials are drawn to service-based churches, like Midtown Fellowship in Columbia, because they are as committed to Jesus’s call to tend to the poor and sick as as they are about having an authentic Sunday worship experience.

Mainline churches, Ratcliffe said, “feel like, ‘if we open the doors, people are going to come.’” But he said attendance numbers are suggesting otherwise.

Graham Harmon, a 21-year-old student and member of Grace Presbyterian, an Associated Reformed Presbyterian church, believes differently.

“The Sunday morning service is not an outwardly evangelical thing, it’s supposed to be a gathering of Christians, the gathering of believers,” Harmon said. “Not to say, people are not supposed to come in who are not believers, not to say there isn’t supposed to be an evangelical component.”

The ARP denomination is conservative and has drawn new members who believe mainline congregations have become too liberal and drifted from the teachings of the Bible. Harmon said he believes many mainline denominations, including the United Methodist Church and PCUSA, have “mythologized” most of the Bible rather than believing in the inerrancy of the Bible.

“They keep a lot of the way things look and feel in the service, right, but I think they’ve abandoned, in a lot of ways, the historic Christian understanding of a lot of things,” he said.

The millennial Christian dilemma isn’t the only issue plaguing Protestant congregations.

In late February, the United Methodist Church at its annual assembly refused to allow homosexuals to be ordained as ministers in the faith, something Fischer believes will cause many churches to break away from their denomination, “not unlike the schisms we saw in the Civil War.”

But religious experts say this type of turbulent change in the Christian faith isn’t new.

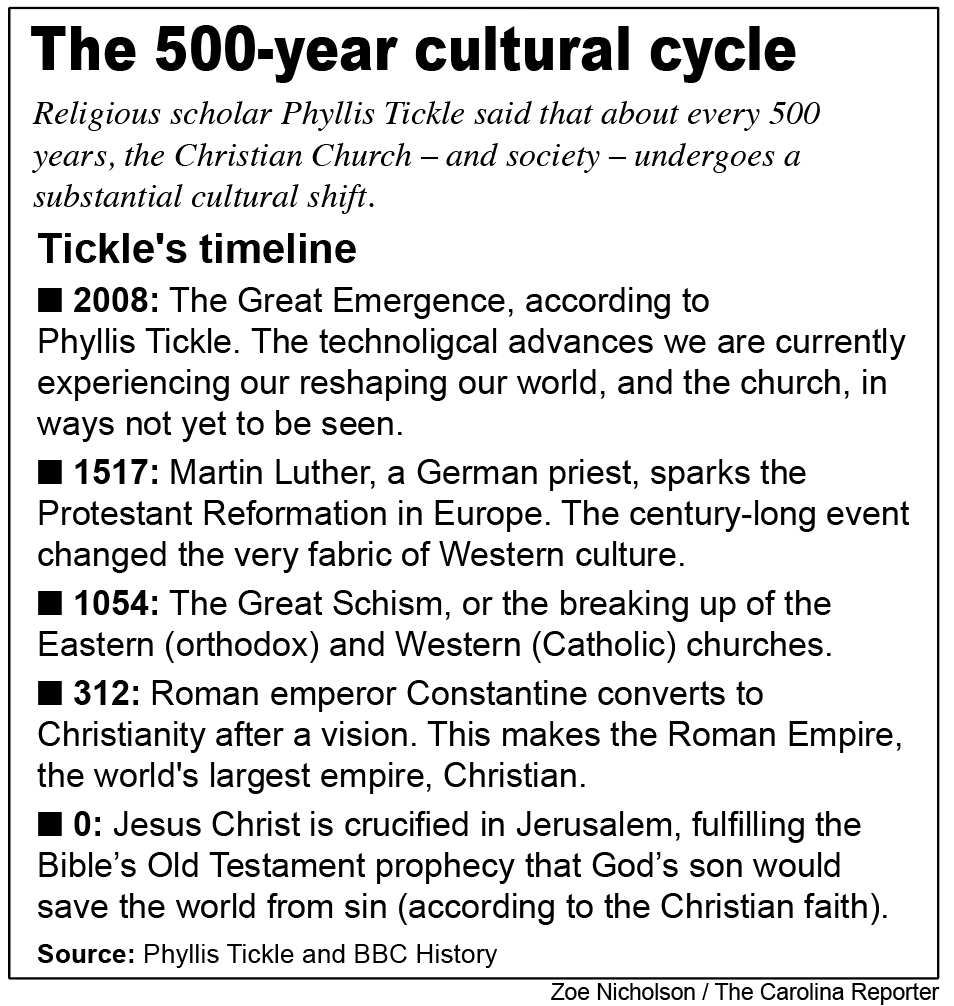

Religious scholar Phyllis Tickle’s 500-year Rummage Sale theory says that the Christian Church undergoes a great cultural shift every half-century. Fischer believes the church is in the midst of one right now, caused by the onslaught of the internet and the secularization of America.

The church doesn’t look like it did 50 years ago, Fischer said, and it won’t like it does now 50 years from now. But, Fischer believes the fundamental beliefs written in the 2,000-year-old text still hold true today, and will hold true forever.

“God is still God,” she said. “And the church has always changed.”

Southern Baptist pastor Jody Ratcliffe started the Church at West Vista three years ago. His unconventional approach to church has made his congregation mostly millennial, a rarity in mainline faiths.

Lutheran pastor Michele Fischer said the church is “slow to change,” which is one cause of the mass exodus of young adults and teenagers from mainline, or traditional, Protestant churches.

USC student Jordan Grimmesey stated she prefers a more spiritual religious experience over a traditional one, a rising trend in yong adults.

USC student Graham Harmon believes mainline churches are losing numbers because of their shift to theological liberalism, or the progressive interpretation of the Christian Bible.