The railroad trestle crosses North Main Street near the Earlewood neighborhood. Leaders are working to help the area redevelop and make it easier to start small businesses.

When Hi Bedford-Roberson and her late husband moved their business to North Main Street two decades ago, they would arrive at work to find discarded drug needles left in the backyard and sex workers patrolling the front.

“It was still kind of sketchy,” Bedford-Roberson, owner of Classical Glass of SC Inc, said. “A lot of people didn’t think that this was a good place for us to move our business.”

An influx of businesses over the past decade have helped make the North Main Street area a nicer place to live and work, Bedford-Roberson said. But residents say the area has a long way to go.

Elmwood Avenue divides Main Street into two halves. South of Elmwood is downtown’s narrow Main Street, full of carefully curated businesses, decorations and foot traffic. North of Elmwood Avenue, however, Main Street widens to a less-pedestrian friendly four-lane road, dotted with empty lots and homeless gathering spots.

Transitions Homeless Center sits near the divide, further discouraging pedestrian traffic and nearby business development.

Residents and business owners north of Elmwood Avenue feel cut off from the rest of the city.

“Elmwood seems to be like a forcefield,” said local business owner Doug Aylard. “People who work downtown don’t go north of Elmwood. Up until recently, there really hasn’t been a reason to come up here.”

Elmwood marks the beginning of the North Main District of Columbia, though residents disagree on what to call the area, alternating between NoMa, North of Main, Main north of Elmwood or the Trestle district of the NoMa district.

“There is a lot of confusion,” said Denise Wellman, president of Cottontown neighborhood, which sits on the north side Elmwood Avenue.

Whatever it’s called, neighborhood and city leaders see the area as city’s next growth spot. And they are working to attract more businesses, connect existing development and bridge the divide that Elmwood Avenue poses while being aware that development can drive up rents and push out longtime residents.

“There’s a lot of opportunity for development when you go north of Elmwood, no matter what you call the street,” Wellman said.

A BIT OF HISTORY HELPS

It all started when Columbia’s population boomed in the 1880s.

A wealthy entrepreneur, Frederick Hargrave Hyatt, extended the trolley lines to Hyatt Park, laying the groundwork for what today is North Main Street. He also established the Eau Claire suburb, which he envisioned to be a whites-only, elite community, Historic Columbia Research Coordinator Eric Friendly said.

But when his idea failed to take off, Columbia College and middle-class white people moved into the area. Neighborhoods developed.

Following World War II, more white middle-class residents migrated from Columbia’s inner city to North Main. At one point, the neighborhoods of Cottontown, Earlewood and Elmwood Park were 96% white, Friendly said.

But that changed when schools began integrating in the 1960s. As Black students and teachers were able to move to Columbia’s downtown, white residents fled for the suburbs. At the same time, the University of South Carolina bought and leveled historically Black neighborhoods to expand its campus, and many of those residents were displaced into North Main public housing, Friendly said.

By 1980, the area was 22% white.

Today, a railroad trestle that stretches over North Main Street near Earlewood Park marks the divide between the predominantly white 29201 zip code on the trestle’s southern side and the predominantly Black 29203 zip code on the northern side.

Attempts to revitalize both sides of the trestle have come and gone through the decades, leaving a patchwork of empty lots and new streetscapes, homeless encampments and coffee shops.

But new developments in the works could transform the area into the more developed vision many have longed for.

“The footprint is definitely getting bigger,” said Matt Kennell, President and CEO of the City Center Partnership. “Probably within 10 years, you’ll be hard pressed to tell a lot of difference between Main Street and North Main.”

A TASTE OF SMALL-TOWN CULTURE

Bedford-Roberson opened Classical Glass of SC at 3031 North Main St. in part because rent in other areas of the city was high, even two decades ago.

She lives in the nearby Earlewood neighborhood, and since a custom stained glass shop doesn’t depend on walk-in traffic, she decided to make it work. An influx of businesses in the past 10 years — including Cromer’s P-Nuts, Carolina Imports and Soda City Movers — have made the area “so much better,” according to Bedford-Roberson.

In the past decade, residents of the three historic neighborhoods in the area decided to “go on the offensive” to recruit businesses, Cottontown resident and former neighborhood president Paul Bouknight said.

“The first couple of (developers) we talked to turned us down for loans because … the financial institution says North Main doesn’t have a good financial history. That wasn’t any surprise,” Bouknight said.

Doug Aylard, owner of Vino Garage Wine and Beer, ran into the same issue.

When he moved to Cottontown 17 years ago, he said his real estate agent tried to discourage him from buying, since it was “the slums.” And he couldn’t get approved for a loan to start his business since the bank didn’t think the North Main area was a viable location.

“Everyone has this negative stigma of this area,” Aylard said. “I would like for people to venture North of Elmwood. … The city has really nowhere to grow but through this way.”

Aylard said he started the business to fill a hole, and hopes to see more independent businesses come in. But increasing rents may make it difficult.

Dana Myers, the owner of Main Street Bakery, landed in NoMa because she grew up in the area. Myers attended Eau Claire High School and Columbia College, which is farther out North Main.

“It’s that old-fashioned, country-style kind of area — everybody kind of knows everybody,” Myers said.

That family feel is what attracted neighborhood presidents such as Wellman to the area.

“We have college students that live here,” she said. “We have retired people that live here, we have single people, we have married people, we have same-gender couples that live here. It’s a really an eclectic, vibrant neighborhood.”

Earlewood neighborhood president Bonnie Slyce likes that it doesn’t feel like living downtown, even though you’re about a mile from the action. She walks to the Soda City Market on pretty Saturdays and jogs early in the morning.

“It seems like you’re always hearing about something new moving into the area,” Slyce said. “There’s still a lot of abandoned businesses and abandoned buildings. But more and more I’m hearing that there are plans in the works for that. … It’s the up-and-coming area.”

A BALANCING ACT

Neighbors have been calling for more development for a decade.

Columbia City Council has spent the past six months passing measures to make it easier to start small businesses.

Costs and permitting associated with utilities, grease traps, parking and landscaping have been reduced or eliminated. Zoning hearings are being held twice as often to speed up the permitting process. And the city’s entryways are being spruced up to make the area more attractive, councilman Joe Taylor said.

Taylor estimates the costs for starting the average business will be reduced by more than $100,000.

“We’ve eliminated a lot of the roadblocks,” Taylor said. “We made it possible to build.”

Though these changes are city-wide, they will especially affect the NoMa area, Taylor said.

Some large developments are already in the works. Peak Drift Brewing Co. soon will open what’s set to be the largest brewery in the state at the old Stone Manufacturing Co. facility.

Several apartment complexes are also in the works. A nearly 250-unit development at the old Jim Moore Cadillac site just north of Elmwood, 50 affordable units at the intersection of Benton Street and River Drive, and 100 units at the corner of Scott and Sumter streets near Elmwood are in the works, according to Columbia’s planning commission.

Some residents are excited about the projects. Others worry about traffic.

“It’s a balancing act,” Statler said. “Everybody wants businesses, and everybody wants development. But with that comes traffic.”

Residents say they want small businesses, such as a butcher or bagel shop, a pet store, unique antique shops or bookstores, as well as more restaurants and even nightlife.

They also desperately want a grocery store.

“We’d love to see the area grow,” Wellman said. “We think that that adds to our neighborhood. We’re not looking for huge kinds of establishments.”

Connecting the neighborhoods north of Elmwood to each other and to the rest of the city is another key, stakeholders say.

Residents want to see crosswalks, bike lanes and traffic-calming measures. Already, the mayor has had preliminary conversations with the state transportation department to add bump outs to narrow the lanes, said Logan McVey, an assistant to the mayor.

“It’s a four-lane, busy road right now,” McVey said. “It’s just not conducive to riding a bike or to walking.”

The goal is to connect each of Columbia’s neighborhoods and allow more people to live in the center of the city.

What people want is “a place that you can live and walk and eat and play and exercise and do all that right around where you live,” McVey said.

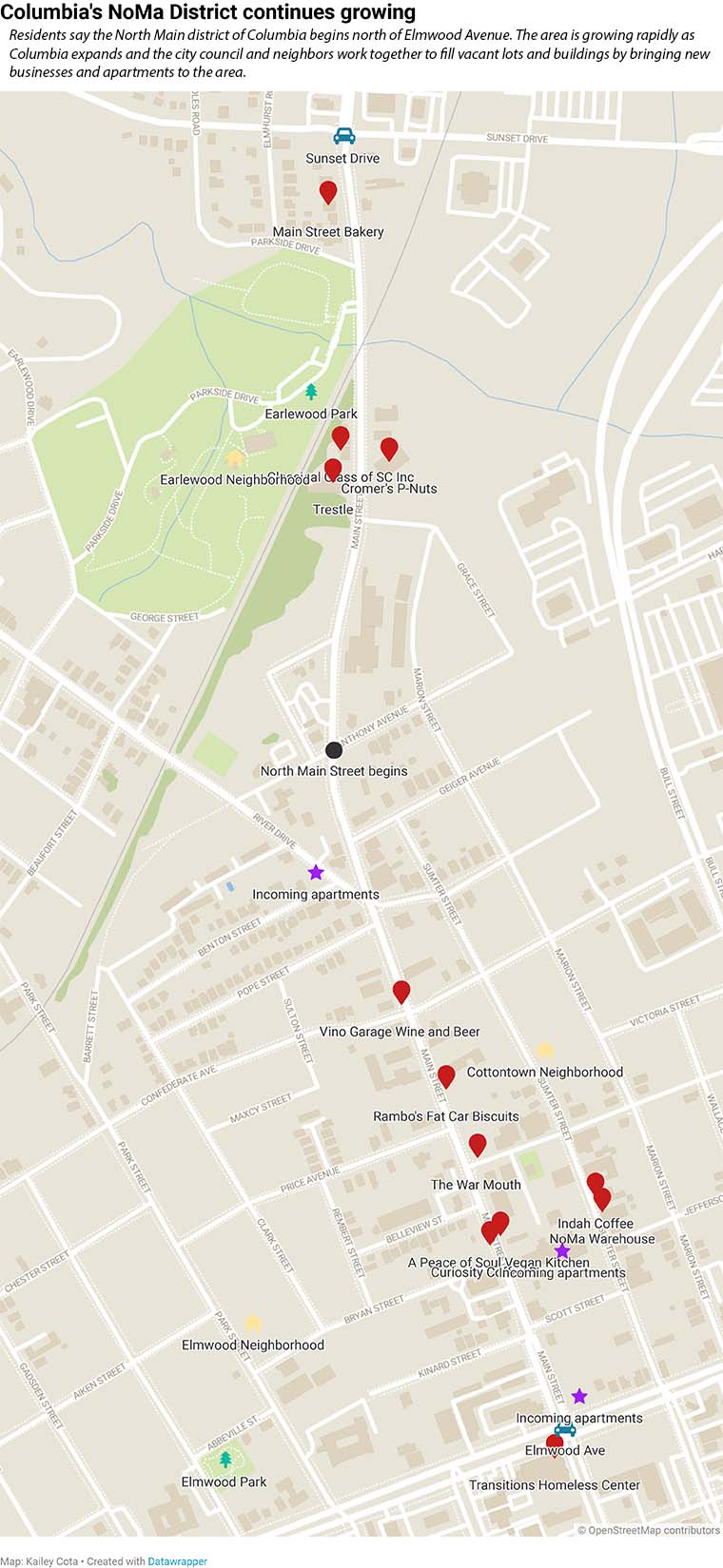

A map of the North Main area of Columbia. The city is expanding as leaders aim to make it easier to start small businesses.

Dana Myers, the owner of Main Street Bakery, prepares cakes to sell. Her business is located in the North Main area of the city.

Stained glass sits in the window of Classical Glass of SC. Hi Bedford-Roberson’s business is located on North Main Street, close to her Earlewood home.

Doug Aylard, owner of Vino Garage Wine and Beer, is located in the North Main area. The area is expanding as leaders aim to make it easier to start small businesses.

Construction litters North Main Street. The area is developing as leaders try to make it easier for small businesses to begin.

A mural at Hyatt Park overlooks the rest of the park. It provides a community space on North Main Street.

Elmwood Avenue divides the North Main area from the rest of the city, community members say. Leaders are working to help the area redevelop and make it easier to start small businesses.

Sunset Drive crosses North Main Street after the trestle and Earlewood Park. The area is redeveloping as leaders work to make it easier to start small businesses in the city.

A time-lapse video on Main Street, from Sunset Drive to the Statehouse