Riverwalk patrons sit at picnic tables along the Saluda River. (Photo by Audrey Elsberry)

The Three Rivers Greenway is one step closer to its goal of connecting downtown Columbia to the Lake Murray Dam.

A 10.5-mile extension from Columbia’s Saluda Riverwalk to the Lake Murray Dam will be built in three phases after funding was approved by Richland County in November.

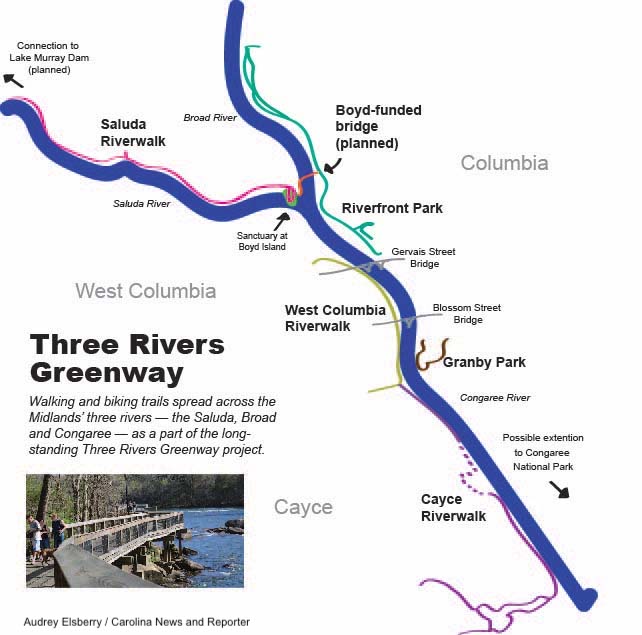

The Three Rivers Greenway is a long-awaited dream for the city of Columbia. The goal is to extend the existing 10+ miles of greenway — creating an extensive path of walkable and bikeable trails that connect communities across the Midlands.

“It’ll become a way of moving amongst our communities a little bit more fluidly,” said Mark Smyers, director of the Irmo Chapin Recreation Commission. “This will provide a much safer (pedestrian) option with a much more desirable route for, you know, regular transportation but also leisure enjoyment.”

The project will intersect with the Carolina Crossroads project, a multi-billion dollar overhaul of the I-20/26/126 corridor.

Smyers said he is talking with the state Department of Transportation about building both projects “cohesively,” instead of waiting for the interstate construction to be completed first.

“We’re hoping that that’s an option, but we really have yet to really tease that all the way out,” Smyers said.

Phase I will connect Lake Murray with Saluda Shoals Park. Phase II will connect Saluda Shoals to the suburb of Gardendale. Phase III will make the final connection to the current greenway north of West Columbia and Cayce in Lexington County.

Smyers said Phase I and II should be open within 2.5 years, but the final phase, which will run under the interstate, is dependent on discussions with the transportation department — but could take until 2028 if the interstate construction gets in the way.

THE START OF THE TRAIL

The complicated, collaborative and time-consuming construction of the newest extension is one example of why the dream of a greenway has an 100-year long history of failure and triumph across Richland County, those involved said.

In 1905, there was a nationwide push to build public parks and preserve green spaces as the nation developed rapidly. Central Park in New York City as well as the National Park Service were established during this time.

Here in Columbia, there was also a plan to build a large public green space along the river between Blossom and Gervais streets. Now, Central Park and the National Park Service are well established — and Columbia’s public riverfront park system remains unfinished.

The area between Blossom and Gervais streets remains untouched, while more than 10 miles of river walks have been built in surrounding areas over the past 20 years.

Mike Dawson helped found the River Alliance in 1994 with the goal of establishing a trail system along the Midlands’ three rivers. The Three Rivers Greenway project was announced in 1996.

Before the River Alliance existed, “there were a few boat landings,” Dawson said. “But most of the edge of the water was private property or off limits, or something else, and you really couldn’t get there.”

City Councilman Howard Duvall sits on the River Alliance board.

“For 25 years, we’ve been trying to get permission through easements, through purchase or whatever, to put a greenway down the banks of these rivers,” Duvall said.

That’s a long time.

“In a perfect world, it would have been done 10 years ago,” Dawson said.

WHAT TRAILS EXIST NOW?

As of December 2022, there are five sections of the Three Rivers Greenway. Only two are connected to one another.

The Saluda Riverwalk

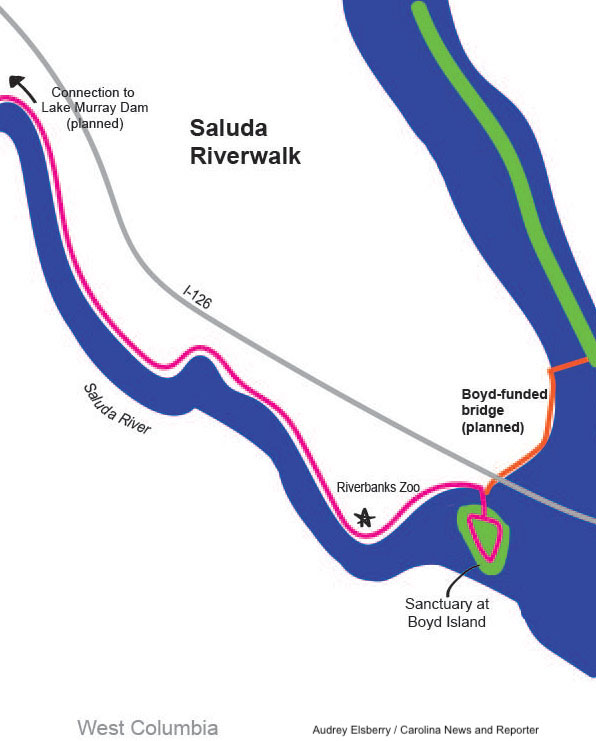

The newest portion of the greenway to open in 2021, the Saluda Riverwalk runs 3 miles along the Saluda River from the I-126, I-26 interchange to where the Saluda and Broad rivers merge to create the Congaree. A small bridge connects the trail to Boyd Island Sanctuary, a sculpture garden. Potentially, the trail could be used as a bike or pedestrian entrance to Riverbanks Zoo.

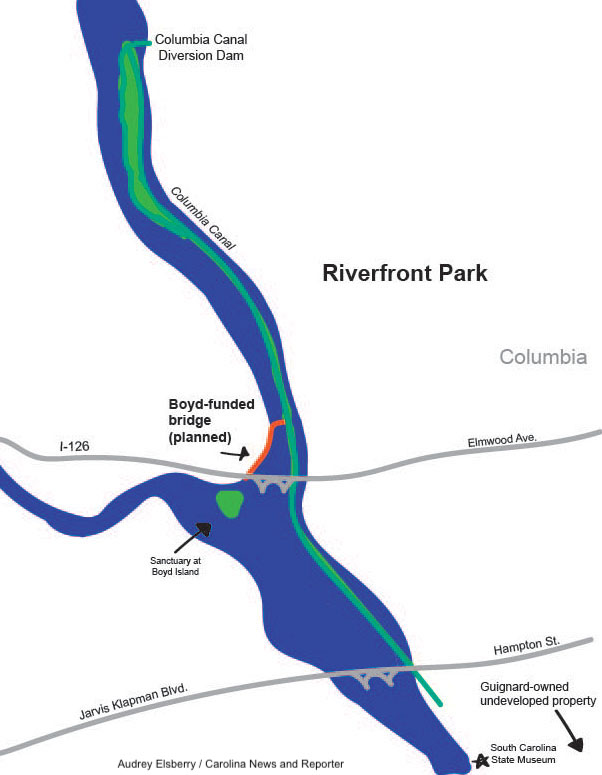

Riverfront Park

Riverfront Park runs 2.5 miles between the Gervais Street bridge and the Columbia Canal dam. It has an upper and lower portion that run parallel to each other — one running along the canal, and another through the tree-lined banks of the Broad River.

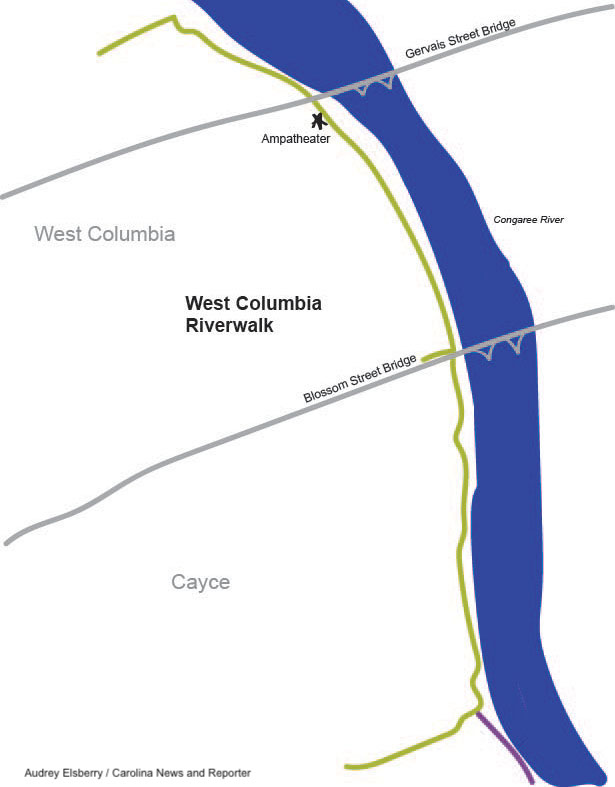

West Columbia and Cayce riverwalks

The West Columbia Riverwalk runs underneath the Gervais Street bridge southward to connect to the Cayce Riverwalk.

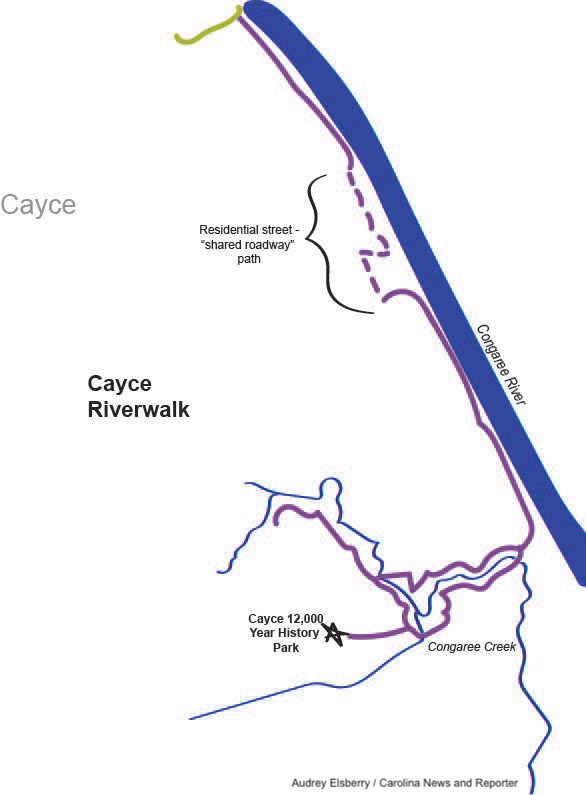

Together, the West Columbia and Cayce trails run about 8 miles. But the Cayce Riverwalk is interrupted by a residential neighborhood. People have to walk along the road for more than one-half mile to continue the trail.

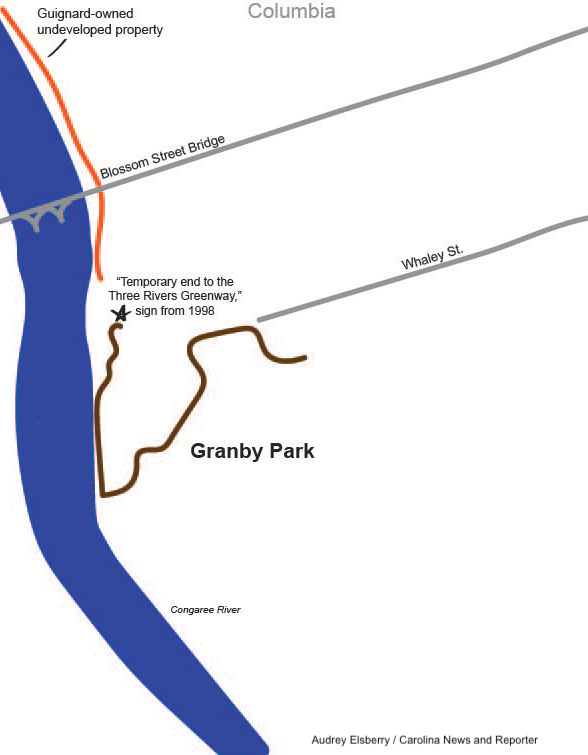

Granby Park

The first section of the greenway to be built, Granby Park opened in 1998 on the Richland County side of the Congaree River. It runs 2 miles from the park on the banks of the Congaree into the city, where it ends near the Olympia Mill apartment complex. Plans call for an extension into USC’s Greek Village. At the end of Granby Park trail stands a sign: “Temporary end to the Three Rivers Greenway.” That sign has been there since the opening of the park.

COLUMBIA FAMILY CLASHES WITH NEIGHBORS

That sign marks the end of Granby Park and the start of an undeveloped parcel of land that is owned by a dynasty dating back to before the city was built.

John Gabriel Guignard was the surveyor general of South Carolina from 1798-1802 and laid out the first streets of Columbia. Descendants of John Gabriel established Guignard Brick Works, which is responsible for making bricks for many of Columbia’s buildings, such as the Olympia and Granby Mills.

Driving over the Blossom Street bridge from Granby Park into Cayce, there are three round, brick buildings that look like huts. These are brick kilns — remnants of the Guignard brick dynasty.

The factory is gone, but the Guignard family trust still owns most of the never-developed land along the river between Blossom and Gervais streets in downtown Columbia.

The lot remains undeveloped because stakeholders can’t agree on what it should look like.

Bob Guild, an environmental lawyer and president of the Granby Neighborhood Association, objected to a 2007 major redevelopment project for the lot, claiming the plans for a 73-acre, grassy park were too ambitious and would destroy too much of the natural landscape.

The $80 million plan, dubbed “Innovista” and modeled after projects in Boston and New York City, called for the removal of most of the trees in favor of low-slung landscaping and non-native foliage, according to the design plans and Guild. A federal grant was needed to fund a portion of the park, but the application was rejected.

“Thankfully,” Guild said.

The modern design did not align with the goal of the greenway, which is to stay “light on the land and (be) nature friendly,” Guild said.

A more recent attempt to create a greenway park design also languished. Architects from Landplan Group South developed the plans, but once again, property owners and city officials couldn’t agree. When Carolina News & Reporter asked if “property owners” meant the Guignards, architect Charles Howell laughed. “I can’t agree or disagree. But, yeah.”

The owners have a major condition to allow development of the Blossom-Gervais property, said Guild — an extension of Williams Street, which currently ends at its intersection with Blossom Street.

The extension to Gervais Street would allow for more economic development along the vacant lot, but requires funding through a federal grant. Columbia Mayor Daniel Rickenmann said he didn’t plan on re-applying for the grant earlier this year, saying the property owners should be responsible for paying for the development of the area.

Four round brick kilns remain on the grounds of what used to be Guignard Brick Works, a multi-generational brick masonry. (Photo by Audrey Elsberry)

PRIVATE MONEY BRIDGES A GAP

The most-recently completed sections of the greenway, the Saluda Riverwalk and Boyd Island, were largely paid for by the Boyd Foundation, a non-profit that funds public projects in Columbia.

In 2010, Donny and Susan Boyd spoke with Dawson about doing a project on the river.

“We got a canoe, and I took them out to the island and said, ‘Hey, yeah, we could do something cool out here,’” Dawson said.

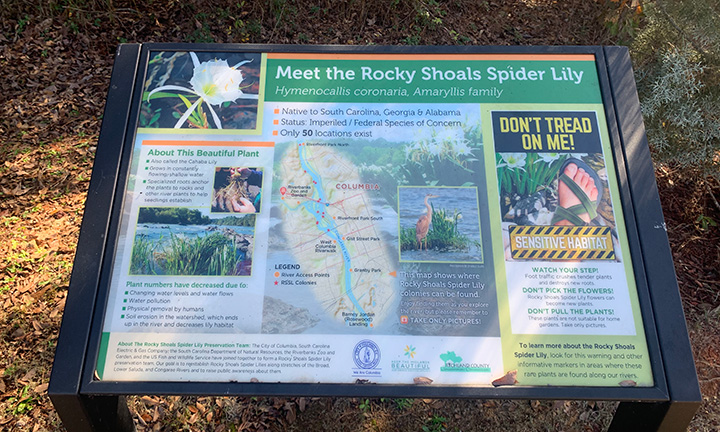

Today, Boyd Island is open but still under construction. Columbia’s arts foundation, OneColumbia, is designing and installing statues and sculptures on the island, highlighting local wildlife. A planned gazebo will be dedicated to the Rocky Shoals Spider Lily, a prominent native plant along the river.

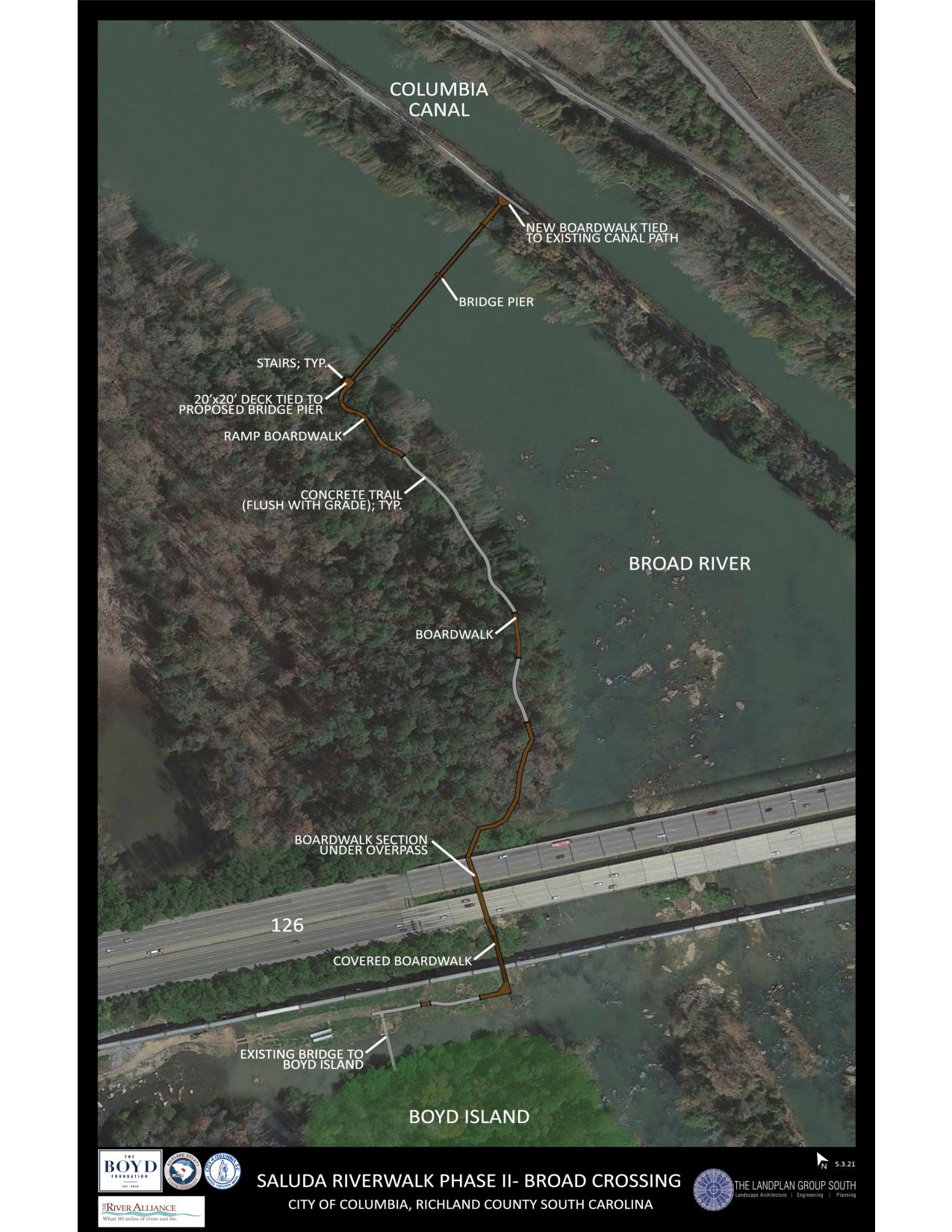

The foundation also is funding a soon-to-be-built bridge across the Broad River that will connect two major sections of the Greenway – the 3-mile Saluda Riverwalk and 2.5-mile Riverfront Park. The bridge, also designed to resemble a spider lily, will parallel the I-126 bridge that empties into downtown Columbia. It will feature viewing platforms for cyclists and pedestrians.

The Boyd Foundation will spend $3.6 million on the bridge. Richland County’s local-option 1% sales tax for transportation will cover the remaining $2.2 million.

WHY IS THIS TAKING SO LONG?

Increased costs and controversy have jeopardized many of the penny tax’s projects, including the greenway bridge.

Bailey sought out Paul Livingston, chairman of Richland County Council, to strike a deal. Bailey told Livingston the Boyd Foundation would pay for the bridge if the county would pay for the land improvements needed around the bridge.

The county agreed. Dawson said he hopes permitting will be ready in the spring of 2023. But delays are possible, largely because of how many entities are involved, he said.

The greenway is an almost 30-year ongoing project, and things have been slow-going. The Saluda Riverwalk, which was finished in 2021, took 18 years to complete, Dawson said.

“Nothing ever moves smoothly in a political environment,” Dawson said.

While some delays are caused by land ownership and funding, permitting is a large reason why these projects take so long to get off the ground.

More than 14 different “permitting authorities” have jurisdiction over the Saluda, Broad and Congaree rivers, Dawson said. The Federal Emergency Management Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers are just two that must give the project a green light.

“If you want to do it instantly, you can’t do it,” Dawson said. “A lot of it is, ‘Can you get the money, and can you get the permits?'”

Because the rivers are considered “navigable,” further permitting and studies are required.

Dawson said permitting for the Boyd Island bridge — which is much smaller than the projected bridge over the Broad River — took about one year.

HIDDEN TREASURE ON THE TRAIL

During construction of the Saluda Riverwalk, a construction worker posted on a Facebook page for relic hunters that he had found Native American artifacts while digging in the parking lot area, Dawson said.

The land where the worker claimed to have found the artifacts was leased to the Riverbanks Zoo from a local power company. The power company sent a letter to the worker who claimed to have found the artifacts, saying “’you looted Indian artifacts from our property — return them,’” Dawson said.

Once Dawson and his team were alerted about the supposed discovery, they halted work at the site and had archeologists search for historically significant artifacts. Construction was paused for about a month. In the end, nothing was recovered, Dawson said.

WHAT DO PEOPLE THINK?

Many stakeholders favor continuing the greenway project, in whatever form, because of the economic development itt could bring to the Midlands’ riverbanks.

The greenway could help businesses recruit employees and persuade them to move to Columbia, said Smyers of the Irmo Chapin Recreation Commission.

“A quality workforce is a high quality of life,” Smyers said. “And so these types of amenities are not only wonderful for the community. … But from an economic standpoint, it’s a business driver as well.”

Some Columbia outdoors enthusiasts say the trails are a great way to get outside and enjoy nature.

At Columbia’s Riverfront Park, near the State Museum, Alecia Green and Micheal Anderson walked along the trail recently. It was their second or third time there together.

“Last time we rode bikes, and that … was fun,” Anderson said.

The natural scenery and nice people drew Anderson to Riverfront Park, he said. He visited the park as a child but hadn’t been since.

“This will be a regular spot” for us, Anderson said.

On the opposite river bank, Lindsay Ravenell and her dog, Savannah, were on their daily after-work walk along the West Columbia Riverwalk.

Ravenell and Savannah have been going to the riverwalk for three years. Ravenell said she’s planning on moving away from Columbia in the near future.

“One of my big criteria is living near something like this, just for ease of access and having something to do after work,” Ravenell said.

(Graphic by Audrey Elsberry)

Map of Boyd Island Sanctuary (Graphic courtesy of the Boyd Foundation)

Map of planned bridge over the Broad River (Graphic courtesy of the River Alliance)

A digital rendering shows what the planned bridge over the Broad River could look like. (Graphic courtesy of the Boyd Foundation)

Rendering of a park between Blossom and Gervais streets (Courtesy of the Innovista Master Plan, Sasaki Associates, 2007)