Camille Graham Correctional Institution in Columbia is one of two all-female South Carolina prisons. The state’s average daily incarcerated female population is about 1,500.

Second in a four-part series

Who do you thank for making your license plate, or for paving the road it travels on?

It could be a South Carolina inmate.

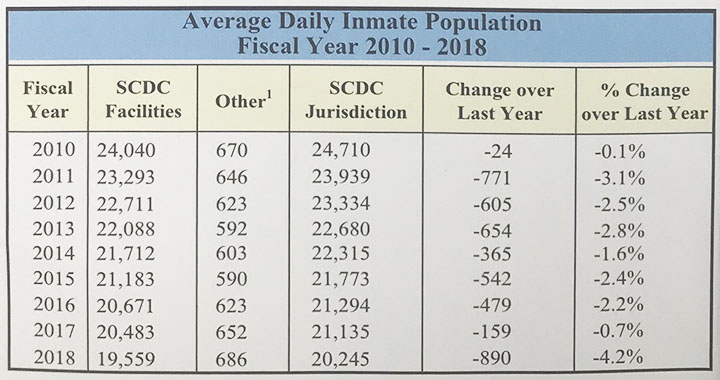

The state has seen its prison inmate population decline every year since 2000, and Bryan Stirling, corrections department director, attributes this to a “re-entry” program for transition back to society and job training.

About 18,800 inmates occupy the Palmetto state’s prisons as of June—a four percent decrease from 2017 and the lowest population in 22 years.

The South Carolina Department of Corrections is also looking to reduce the recidivism rate, or the number of released inmates who return to prison within three years.

This is against the backdrop of a national push to move prisoners convicted of drug and other non-violent offenses out of state and federal prisons and back into society. A bipartisan criminal justice reform bill that has the backing of President Trump would ease mandatory sentences and give judges more leeway in sentencing. But supporters are frustrated by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s refusal to bring it to the floor of the Senate.

For about 22 percent of released inmates, the next place to go could be back to prison. But that number is “an all-time low,” Stirling said.

Stirling attributed the shrinking numbers to a pre-release program for inmates with six months left on their sentences. This works to train inmates in areas like proper job interview attire or facing employers who ask about their incarceration, Stirling told the Associated Press.

The statistics are good news for a department that has come under fire since a bloody riot at the Lee Correctional Center in Bishopville that left seven inmates dead and many others injured. The department was excoriated for failing to contain the riot for seven hours and for housing competing gang members in the same prison. The department is expected to face lawsuits for years to come.

In October, a guard at Lieber Correctional Institution in Ridgeville was arrested after allegedly having a sexual relationship with an inmate and helping him smuggle contraband and a gun into the prison.

An inmate reportedly died last week at Lieber, but no details on the cause of death are available. As of this year, the inmate to correctional officer ratio at Lee Correctional Institution is about 200 to two.

The federal “three strikes” laws enacted in 1996 aim to remove repeat offenders from society for good; a person who commits three felonies can receive a life sentence without parole.

In South Carolina, the first strike is for a “most serious offense,” which includes crime such as homicide, first degree assault, criminal sexual conduct, kidnapping or burglary in the first degree. The second and third strikes can be a “serious offense,” some of which may be non-violent: trafficking drugs, insurance fraud or embezzlement of public funds.

Conduct violations on the inside or “three strikes” convictions can keep many inmates behind bars for a long time, but the numbers are still going down every year. SCDC spokesman Dexter Lee said that consistently releasing non-violent offenders plays a role in the declining population.

“We’ve been doing a pretty good job of getting them out,” Lee said.

Of the releasees who do end up coming back, about 85 percent are actively working to break the cycle, Stirling said. Other than the pre-release program, inmates also take classes to earn a GED or participate in work programs or labor crews.

Some inmates, for example, make South Carolina license plates.

About 17 percent of releasees who returned earned a GED through the SCDC education program. Stirling also said the department partners with businesses to potentially connect inmates with jobs upon their release.

The SCDC purchased forklifts and paving equipment so inmates in the work program can learn how to operate it and offer their skills to a future employer.

Purchasing that machinery is also beneficial to the economy, Stirling said, because the institution can now pave their own roads.

“Let’s give them the opportunity to build the ladder, and to climb it,” Stirling said.