Coffee is known for being hot, dark and bitter, but local micro-roasters are roasting beans from all around the world and making it an art form.

There are dozens of local coffee roasters in South Carolina, and hundreds nationwide. Green coffee beans are shipped into the U.S. from all over the world then heated to around an aromatic 400 degrees, landing in coffee shops, the shelves of local stores and the homes of coffee aficionados everywhere. What makes these beans different from commercial companies is the personal touch and small batches.

Columbia, South Carolina is an enthusiastic player in this coffee trend.

Indah Coffee Company, Immaculate Consumption, Loveland Coffee, Haven Coffee House, Iron Brew Coffee and Lake Murray Coffee Roasters are just a few of the roasters in the Columbia area. They each have a distinct way of roasting beans and developing customer relationships. Roasters may roast as little as 2 pounds at a time up to 10 kilos.

More than just creating a drink, these roasters believe they are creating an experience for their customers, and doing so ethically.

The ethics of coffee

Coffee beans are harvested mainly from developing countries including Colombia, Indonesia, Ethiopia and India. These farmers usually earn less than 10 percent of the retail profit. For decades, the coffee industry was also tarnished by allegations of modern slavery and many times laborers are still effectively enslaved or are child laborers.

In 2018, there were reports of forced labor at a farm in Brazil that supplied beans to Starbucks. In Brazil, workers earn less than two percent of retail profit.

In recent years, importers have started forming relationships directly with farmers. Micro-roasters, in turn, know the importers and often times the farmers so they can ensure their coffee is fair-trade.

Indah Coffee Co. has been a local roaster in Columbia for almost a decade, partnering with fair-trade importers.

Mills Eddy, Indah’s coffee roaster, said that the owners of Indah wanted to make sure this was a part of the business.

“Slavery is still a big part of supermarket brands; we aren’t affiliated with that at all,” Eddy said. “They discovered what wholesome coffee farming looked like, and what roasting coffee looked like and how that freshness set that coffee so much apart from the cheaper brands.”

One of Indah’s main importers is Royal Coffee in New York. Royal partners with farms and even supplies Eddy with the name and background of the farmer who grew the beans.

“Coffee for a long time has abused the people who made it, especially in Brazil which was one of the top producing countries, said Eddy. “Slavery on plantations was a huge thing. But Royal seeks to partner with local farmers so that they can survive and thrive and make money off the products so they can live.”

According to the Food Empowerment Project, many coffee workers are enslaved through debt peonage, which is forced labor to repay debts they owe.

Beach Loveland, the owner of Loveland Coffee, took a trip this month to Guatemala to visit the farms that supply his company’s beans. There they were able to see the process and meet the workers who harvest the beans, a connection he could make because he is a micro-roaster.

Buying from importers not only makes certain that they are getting ethically-sourced coffee, but it also helps micro-roasters offer their customers variety and quality.

The art of coffee roasting

A shipping container of coffee contains about 37,500 pounds of a single origin coffee. Smaller companies have no way to diversify their brand if their money is tied up in green coffee. Importers make it possible for micro-roasters to buy the coffee beans they need to offer customers a variety of flavors. Coffee roasters can purchase different origins in smaller batches from importers.

Roasters say this process is somewhat of an art form.

Every roaster in Columbia has a different process to roast their beans. Not only do they have beans that grow in different soils and at different altitudes, but they also roast at different temperatures and use different techniques to cultivate their own unique flavors.

Micro-roasters are set apart from commodity coffees for ethical reasons, but their standards are also different. The Specialty Coffee Association ranks specialty coffee beans on a 100-point scale. Defects like discolorations, deformations and chemical tastes are a point deduction, and specialty coffee must be 80 points or higher.

Their processes are also very detailed and data-driven. Each roasted batch is monitored and special. Most roasteries purchase coffee once a month and roast weekly, keeping the coffee fresh.

Eddy watches a computer screen with information and graphs to manage the roaster and to control air flow, pressure, and temperature. Minute details and changes can change how the final product tastes in a matter of seconds.

“You can bake the flavor out of the coffee if you go too slow, and it just tastes bitter and burnt,” said Eddy. “Go too fast and you could leave a lot of acidity and a lot of astringent flavors that you don’t want.”

He is constantly tweaking his roasts, and never gets one where he wants it the first time.

“Roasting offers me an opportunity to be extremely creative in an extremely data-driven and precise manner. It’s like I make minor gas and air flow adjustments and I look at a computer that has a graph on it,” Eddy said. “I’m doing all this scientific stuff so I can produce something that has fruity and bright characteristics and it’s an enjoyable experience that doesn’t seem precise, it seems like art.”

Michael Washburn, the roaster for Lake Murray Coffee Roasters, gets excited to try new things with his roasts.

“I think people like that, they like change, they like choice… they like having and experiencing coffees throughout the world,” said Washburn.

Jim Huthmaker, owner and roaster for The Haven Coffee House in Lexington, has been on many trips to Guatemala to learn about the process. He even created his own signature blend called “The Smokejumper.”

“It’s really dark, he describes it as silky and smooth,” said Maggie Coker, The Haven’s manager. “It kind of tastes like a really smokey piece of meat but as a cup of coffee.”

These roasters experiment, fail and work at making something their customers will enjoy.

“Coffee has way more to offer than just a bitter black drink that has caffeine in it. It can be an art form, it can be a way to express something with a drink and really bring out what the farmers have worked hard on,” said Eddy.

Mark Maddaloni considers himself picky about the coffee he drinks. In terms of taste, he looks for how sweet or bitter the coffee is and if there are notes that taste nutty, earthy, chocolatey or fruity.

“I think that a lot of times people think that coffee is just supposed to be bitter, but that’s not really the case. If you have a really high-quality coffee it can taste sweet,” said Maddaloni.

Since becoming a coffee aficionado, Maddaloni has learned more about coffee origins, the roasting process, and different flavors you can taste in a cup. He sees the importance of supporting local roasters and coffee shops.

“I honestly think that it’s better. It’s a better experience, better taste,” said Maddaloni.

The community of coffee

Roasters know the communities they are roasting for and try to get what the customers like and desire.

Many roasters have brick-and-mortar shops where their coffee is sold, but others sell at local coffee shops and stores.

Indah, Immaculate Consumption and The Haven have their roasters on site so customers can see them. Iron Brew Coffee sells in local grocery stores and coffee shops. Loveland has plans to move into a location where they can have an in-house roaster as well. Other roasters like Lake Murray Coffee Roasters are also looking to move into a commercial area where this is possible and they can form a more tangible community around their coffee.

The Haven Coffee House is a non-profit and supports a local non-profit called Lighthouse for Life, which works with victims of sex trafficking.

Eddy sees this community around the coffee he roasts. He sees people appreciate that he’s roasting fresh coffee locally and that there is a place where people can come together and enjoy it.

“Being a local roastery, it’s about knowing what people want, offering that to them, but also with something new included that they’ve never experienced before so they get the combination of ‘oh this is a familiar cup of coffee. This is enjoyable, but oh hey I taste this little bit of difference,’ and it sort of introduces them into a world they haven’t experienced before,” said Eddy.

Coffee beans travel thousands of miles after a farmer pours his hard work into farming them. The farmer decides how long to keep the beans on the plant and that in itself adds different flavors. A roaster gets his hand on the beans and roasts with creativity in mind, and the customer ultimately buys the beans or the coffee.

These connections, Eddy feels, makes the difference between a cup of coffee and an experience with micro-roasters.

“It connects three people that would never otherwise have an interaction. They get to meet in the middle of this cup of coffee that has all of this complexity and all of this story.”

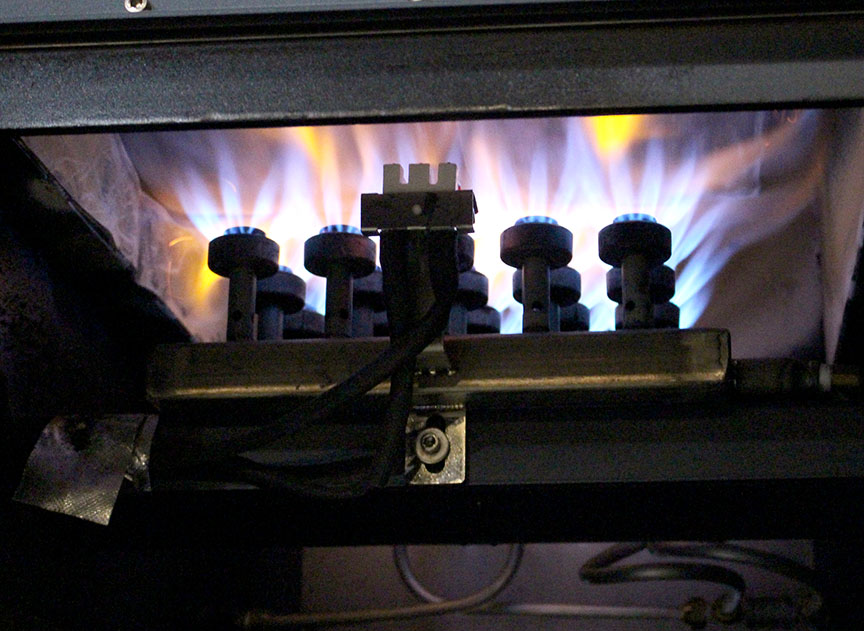

Indah Coffee Company’s roaster, Mills Eddy, monitors the temperature, air flow, and time during the coffee roasting process.

The drum on a coffee roaster has to be heated to over 300 degrees before the roasting process can begin. This process can take up to half an hour.

Coffee roasters get coffee from all around the world to create different flavors as they roast.

Locally roasted beans are used in various coffee shops around the city to create artisanal drinks and brews.