A photo of the South Carolina State House. Photo by: Bee Brawley

South Carolina’s latest abortion bill could create multiple logistical problems for those seeking to get abortions.

If passed, the bill, dubbed the “South Carolina Human Life Protection Act,” only would allow physicians to perform an abortion after the sixth week of pregnancy if:

- it protects the life of the mother

- a deadly fetal anomaly is detected and confirmed by two doctors with a specialty in obstetrics or the area of medicine in which the anomaly is diagnosed

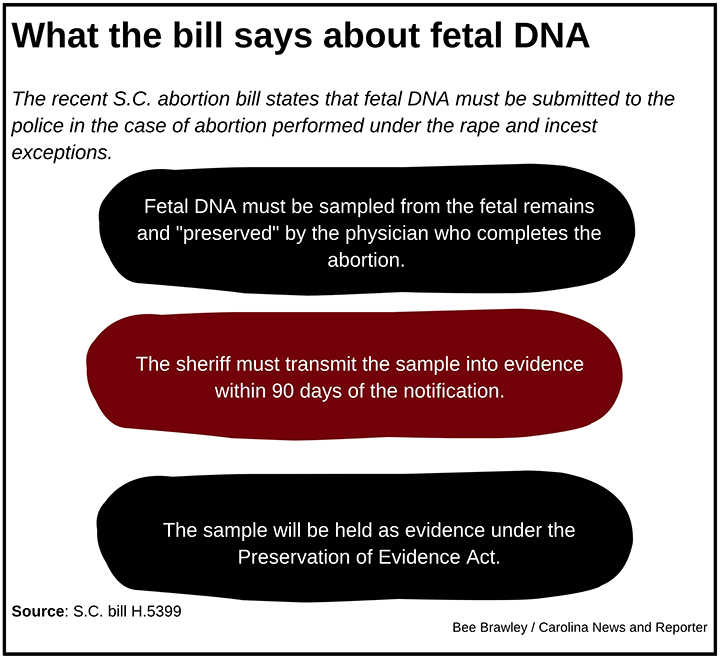

- someone is the victim of rape or incest and seeks an abortion within 12 weeks. This exception requires doctors to report the abortion and submit a fetal DNA sample to their county sheriff’s department.

The specifics of the bill, some say, raise more questions than it answers.

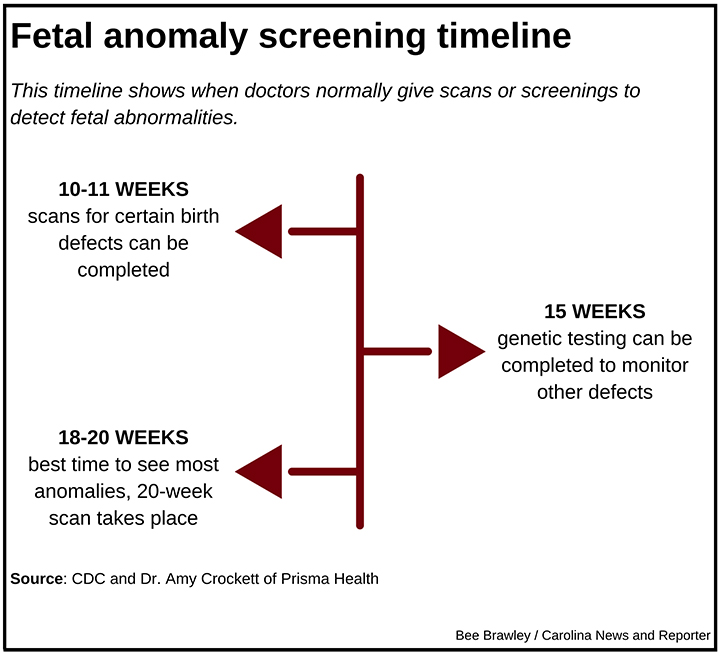

Screening tests for fetal abnormalities happen at different stages, said Dr. Amy Crockett, an OB/GYN in Greenville and the S.C. chair of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

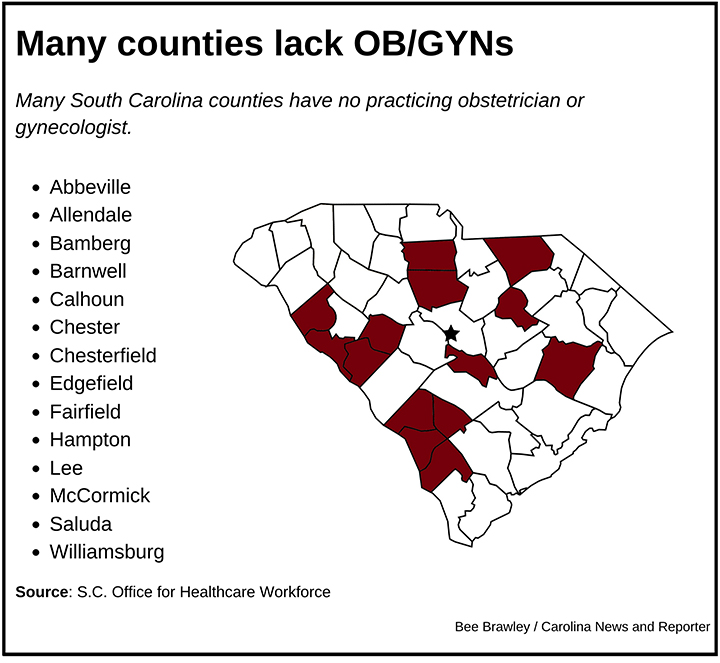

For some South Carolina residents, these visits would require extensive travel.

“Across the state there are centers of expertise where the local OB/GYN can refer patients in when they have questions or concerns about things that are happening when pregnancies are becoming more complex,” Crockett said.

The state already experiences issues with access to prenatal and maternal care. There is an ongoing OB/GYN shortage. Fourteen counties have no practicing OB/GYN, according to the S.C. Office for Healthcare Workforce.

The fetal anomaly is confusing many.

Dr. Deborah Billings, a reproductive health expert at USC’s Arnold School of Public Health, questions how some S.C. residents will deal with the financial implications of this requirement.

“Is Medicaid covering these kinds of visits?” Billings asked. “Is private insurance even covering these kinds of visits?”

The bill also is vague about rape and incest cases.

While the bill requires physicians to submit fetal tissue DNA samples in the cases of rape and incest, it has no language describing the process doctors should go through to submit fetal DNA to law enforcement.

“There is no plan whatsoever,” Billings said. “I’ve got this fetal tissue that has DNA. Now, what do I do with it? Do I put it in a vial and send it off to the attorney general?”

In fact, the bill requires the sample be given to the sheriff’s department of the county in which the abortion is performed. The Richland County Sheriff’s Department did not agree to an interview but emailed a statement referring to the Preservation of Evidence Act, which guides statewide practices for post-conviction DNA testing. It is not clear how “post-conviction” applies to fetal DNA from abortions.

Ann Warner, the chief executive officer of Women’s Rights Empowerment Network, added that the DNA sample collection is an unfunded mandate. “Nobody has said anything about how that’s going to be done – how it’s going to be paid for.”

The bill also is vague on the timeline for fetal anomalies. It sets no limit for when an abortion might be performed under that exception.

S.C. House representative William M. Chumley, R-Spartanburg, expects the House will address that.

“I think that discussion will come up, yes,” said Chumley. “I think that will be something that we’ll be talking about as we take up the bill.”

Again, timing could pose an issue.

According to the CDC, scans for certain birth defects – such as chromosomal disorders or heart problems – are typically completed between 11 and 13 weeks of pregnancy.

There are scans designated specifically for the second trimester, according to the CDC. Between 15 and 20 weeks of pregnancy, screenings are performed to check for birth defects, such as structural anomalies. If a time limit is added to this abortion exception, it may be too tight of a window to practically get an abortion.

“The best time to see the most anomalies is during the 20-week scan, which is usually done between 18 and 20 weeks,” she added. “It’s just because a lot of the fetal structures are so small, even still at 20 weeks. They’re very small. The heart at 20 weeks is about the size of my thumbnail.”

Equally troubling, some supporters of abortion access say, is that the bill could further limit women’s access to doctors.

The bill might discourage future OB/GYNs to practice in South Carolina, said both Billings and Crockett, since failing to comply would be a felony punishable by up to two years in prison. Additionally, physicians who violate the bill would have their license revoked.

“I think it’s intimidating for people to move to a state that is talking about, you know, punishing physicians with felony for practicing evidence-based best practices,” Crockett said.

State Sen. Sandy Senn, R-Charleston, doesn’t think the bill will pass.

She does, however, think we’ll see legislation like this again.

“I’ve only been in the Senate seven years,” Senn said. “And I think we’ve debated something along these lines every single year. It’s like Groundhog Day.”