Greenville County is among the top five hotspots in South Carolina for human trafficking. (Photo courtesy of Upstate Freedom Walk)

Hysteria ensued when a man took a TikTok of his daughter’s car. He explained to his virtual audience that she works late hours, and some mornings, he’s found black zip ties on her car’s rear-door handle. She had no idea they were there.

He said he thought the zip ties were being used by human sex traffickers to mark women for capture.

The video, and others like it, have proliferated on social media in recent years. Unusually high-priced items on Wayfair’s website were believed to be selling children, according to director of the S.C. Human Trafficking Task Force, Kathryn Moorhead.

“When that … started circulating on social media … it drove the calls to the National Human Trafficking Hotline through the roof,” Moorhead said. “I mean, it was thousands of calls that swamped them with people asking about that.”

The issue isn’t a just national one, however.

A 2021 report from S.C. officials shows a 15% increase in human trafficking reports from the previous year. Horry and Richland counties were the top hotspots for trafficking. And the number of cases are on the rise. Differentiating between hoaxes and real cases keeps law enforcement from wasting their time.

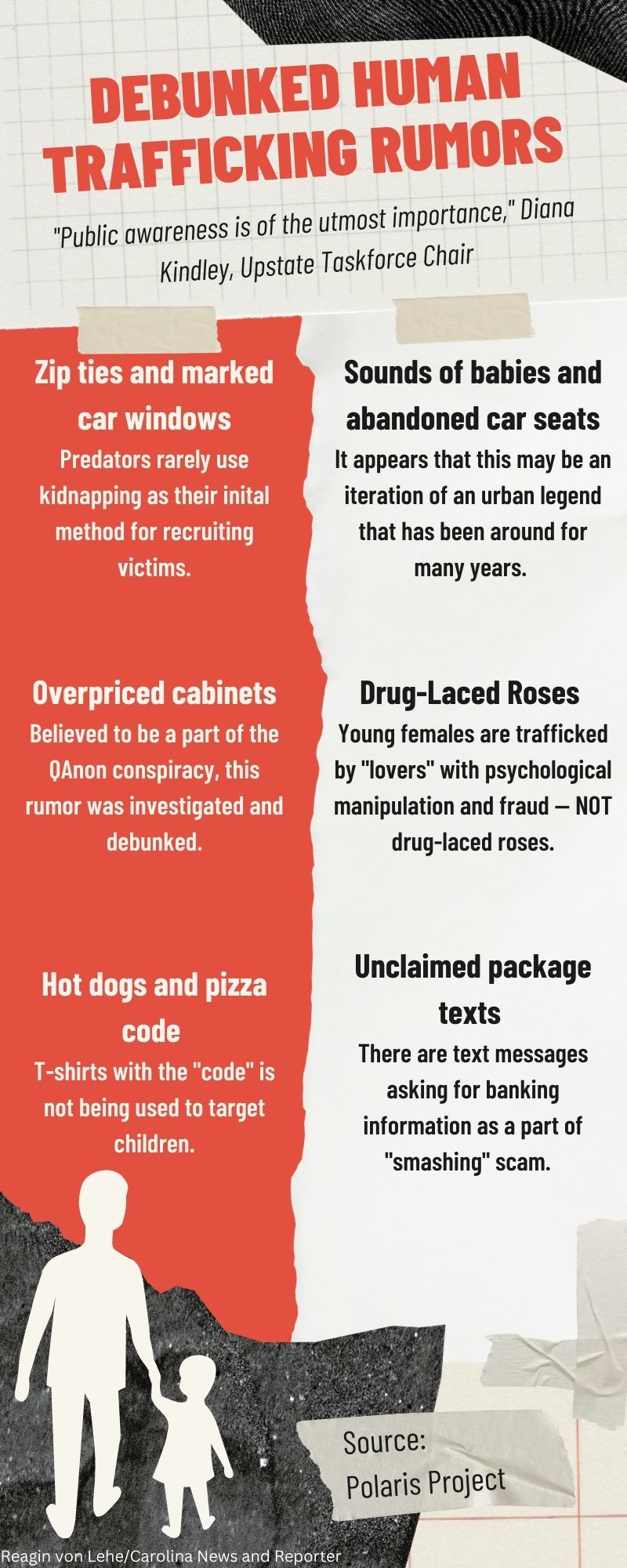

In the case of the zip ties, the Polaris Project, which runs the National Human Trafficking Hotline, debunked the TikTok theory.

The Polaris Project goes through thousands of phone calls and assesses cases with local law enforcement to determine if the cases are genuine trafficking situations. Other debunked rumors are:

- Recorded sounds of babies crying and abandoned car seats are luring good Samaritans into being kidnapped.

- Drug-laced roses are being used to incapacitate, kidnap and traffic people.

- Web sites that claim to be selling children’s swimwear are actually trafficking children.

Now, national and local groups are sounding the alarm on these high-profile hoaxes from social media. Experts say the rumors are overwhelming the national hotline and distracting from the reality of how human trafficking victims are recruited.

To combat misinformation, Moorehead said there are plans at the state Attorney General’s office to follow the Polaris Project’s lead and curate a social media campaign of debunked rumors.

The state’s human trafficking task force releases its annual report every January using data gathered from the Polaris Project.

“It’s pretty comprehensive,” Moorehead said.

Moorehead said debunking false rumors is more important than ever because of the increase in sex and labor exploitation cases. Headline-grabbing and fear-provoking abductions, as those spread on social media, are rare when it comes to sex trafficking.

Sharon Rikard founded Doors to Freedom, a residential facility in Summerville for recovering young female trafficking victims. She said people tend to equate human trafficking with movies such as “Taken,” only worrying about children when they leave home or go missing.

However, most confirmed cases of human trafficking involve slower, long-term psychological manipulation of potential targets, which is harder to recognize.

“Every single child with a cell-phone in their hand is a target for a predator," Rikard said.

Rikard said the girls she oversees have never told her about kidnappings, just online or in-home liaisons. The stories typically involve predators appealing to young girls’ emotions. They can tell them they’re beautiful and provide needs that aren’t being met by anyone else in their lives. A lot of girls said they were coaxed by offers to pay for their nails or hair appointments.

“If a predator can control their emotions, they can control their whole body,” Rikard said. “We live in a fatherless society. … What is every young girl looking for? Acceptance and love. And they will tell me that.”

Diana Kindley, co-chair of the Upstate Regional Human Trafficking Task Force, said traffickers use physical force only as a last resort, when the victims quit being cooperative.

“I can say that I don’t know of any cases in the Upstate where anyone has been kidnapped because of car markings,” Kindley said. “Rumors invoke feelings of horror and shock and cause confusion and misinformation of the true problems and red flags of human trafficking."

Moorehead, with the South Carolina task force, recalled a case that she thinks “speaks to the importance of understanding the psychological … victimization.”

A young girl her team worked with was nearly burned to death by her trafficker, Moorehead said but still begged to return to him because, through trauma bonding, she viewed him as her boyfriend.

“We call it the Romeo trafficker — romancing somebody younger or trying to step in and become their support system, ... building a bond between them before they’ll exploit them through commercial sex,” Moorehead said.

Human trafficking, including sex and labor, has been on a steady incline as the population increases. However, other issues are also contributing to the rise.

COVID-19 caused impoverished areas to grow and made human trafficking more difficult to monitor, as law enforcement and social services experienced staffing shortages.

So the official number of reported cases fell, while the true number of victims most likely increased.

“I often say that poverty fuels the crime,” Moorehead said. “Folks losing jobs, lower incomes, people stuck at home together. ... We know there was a significant increase in child abuse in general just months into COVID."

She remembers being shocked by domestic violence percentages in 2021, saying a lot of these crimes will intersect. She believes economic insecurities following the pandemic ramped up numbers.

As human trafficking has increased, Rikard, Moorehead and Kindley all agreed social media became a major driver in the trafficking and exploitation of minors.

“I mean, (we have) stacks of sheets of paper of one-liners these predators use (on) hundreds of girls waiting to see who will respond — and it just narrows it down for them,” Rikard said.

It's a numbers game.

The state's task force is hiring more employees to bring prevention education initiatives to schools and youth groups across the state. When asked for specifics, Moorehead said they are still "working some of the kinks out."

Kindley, with the Greenville County Sheriff’s Office, thinks the state has made significant progress since the Trafficking Victims Protection Act was passed in 2012, but there’s a long journey ahead.

“A lot more needs to be done,” Kindley said. “Government needs to step up with funding to support those already in the fight. In my opinion, all regional task forces should be funded (more), because this is a full-time job.”

Rikard thinks the State Law Enforcement Division needs to hire additional agents because the crime often crosses county and state lines.

In 2021, around 200 victims of human trafficking in South Carolina applied for aftercare — care beyond basic child abuse therapy.

“You can’t just throw those kids in the same (abuse) category and manage their cases in the same way,” Rikard said. “It’s specialized care. I don’t know that we write legislation from that perspective.”

Rikard continues to say people who use the victims receive a “slap on the wrist” for first-time, and even second-time, offenses. And when victims are assimilated back into society, they often live in fear of their former predators. Stronger legislation could bring steeper punishments for offenders and act as a deterrent, she said.

Rikard also urges people to educate themselves using reputable websites on red flags and how to spot a victim. She said if anyone has concerns regarding social media trafficking rumors, they should reach out to local law enforcement.

“I realize that, like the war on drugs, it may be an ongoing issue," she said. "But as long as dedicated people are involved, … we can help ease the pain and destruction human trafficking creates for our most vulnerable.”