Handcrafted mermaid pots at the South Carolina Artisan market show a contemporary artist’s personal twist on traditional face jug pottery. (Photos and photo slider at bottom by Lauren Leibman)

Craig Watson comes from a family of medicine makers and herbal healers.

A gentle and soft-spoken man, he is a descendent of the Gullah-Geechee people of Charleston and the son of a woman he claims has a “green arm,” never mind the thumb.

He grows plants and studies herbs in the tradition of his family. But from the foundation of his roots, he has sprouted a new way to honor his seaside and soil-based heritage: spice making.

Most Saturdays, Watson can be found selling his spice blends at the Meeting Street Artisan Market in West Columbia. He initially felt out of place vending alongside woodcarvers and jewelry makers. But he considers what he does to be a kind of folk art or artisanal craft, and draws inspiration from his upbringing and cultural heritage.

The tradition of folk art survives today in South Carolina. But many artists are transforming and evolving it from its original concepts. Centuries-old techniques and available materials are making way for new materials and personal twists as artists change with the times.

Change and tradition can go hand-in-hand, said Kate Hughes of the University of South Carolina’s McKissick Museum’s Folk Life Resource Center.

“One thing about traditional culture is that, you know, it’s very adaptive,” said Hughes, the museum’s curator of cultural heritage and community engagement. “It’s a lot of working with what you have and what’s available to you. I mean, that’s how it came to be in the first place.”

For many, this evolution is a choice – a way to weave self-expression and modern resources into traditional forms and styles.

Watson uses creativity and commissions from others to create spice blends such as Hennessy peach churro seasoning and coconut rum-infused jerk. Though these may not be traditional blends, the ingredients are all-natural, and he does the work by hand – peeling fruit and chopping and mixing herbs the way people have for centuries.

Changing materials, new twists

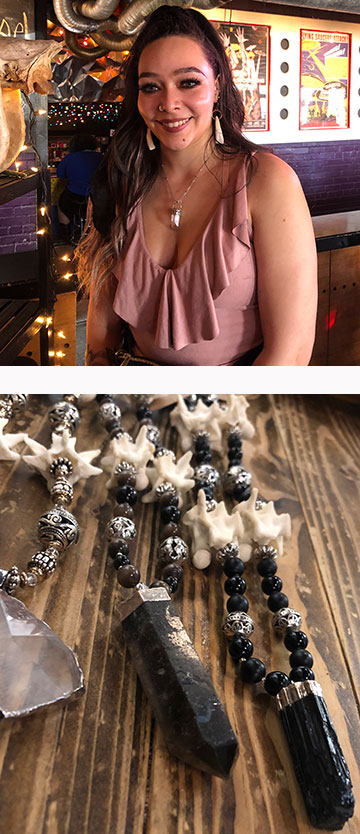

Rainne Orris of Columbia is a jewelry maker who sells her work at Y’all-Mart, an alternative flea market. She is tattooed with dark blooms of flowers, crystals and skulls that unfurl from her elbow down to her fingers.

She recently stepped outside the bounds of traditional jewelry making. But she stays true to the origins of the craft by centering her pieces around ethically sourced bones, stones and even petrified wood.

Some of her latest works feature crystals with metal melted over top to create a dripping, web-like design where the pendant attaches to the chain.

“I don’t really know anybody else who’s doing it quite like this,” she said.

Orris said her African American, Native American and Irish background influences her work but doesn’t define it.

Though she is deeply inspired by traditional Native American art, she makes a point not to appropriate or copy that work. She finds inspiration in places such as nature, music and dance, which come together to make pieces that are unique to her.

Orris and her partner, Jacob, a 3D printing artist, embrace the availability of new technology and changing societal attitudes. They have introduced 3D-printed, life-sized skulls with a base of soy resin to their inventory. Orris calls these her “vegan” skulls.

Hughes and Amanda Malloy, folklife program director at the McKissick Museum, said other artists are adapting out of necessity. Climate change, as well as new development and construction along South Carolina’s coast, have made it difficult for traditional seagrass basketmakers to access materials.

Sweetgrass basketmaking is a Gullah cultural practice preserved in Mount Pleasant and Charleston that has become one of South Carolina’s most well-known traditional art forms. The baskets were historically used to process rice, but today are more commonly used as decorative pieces.

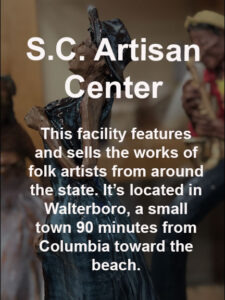

David Smalls, executive director of the South Carolina Artisan Center in Walterboro, about 90 minutes southeast of Columbia, said there also has been a shift toward using old techniques but creating nontraditional items, such as sweetgrass earrings and miniature baskets that have little functional use.

But sweetgrass has been scarce in recent years, so artists have been forced to rely more heavily on accessible materials like the stiffer bulrush, Hughes said.

“It’s a trend that we’re going to see more and more as resources deplete …,” Hughes said. “That’s an issue that’s happening everywhere to many, many different forms of cultural practice.”

Keeping the tradition alive

Resource availability and other issues could make it difficult to physically preserve traditional folk art practices, Hughes said. Sharing the heritage and stories behind these art forms is important to ensure they’re not forgotten.

Levi Wright can be found with his hands and forearms caked in clay, doing just that. He sits at the pottery wheel in the back of the State of the Art Studio in Cayce, demonstrating the proper way to mold and guide the clay to one of his students. He also has found success in his own work as a folk potter.

The combined studio and gallery space, which Wright owns, primarily features local folk artists or crafters. Aside from displaying their work and offering pottery lessons, Wright said he honors the history of folk art by talking about it with the people he encounters.

“I think sharing with people is the main thing of keeping it alive and keeping the heritage going,” Wright said.

He was originally educated as a sculptor, but he pushed himself to explore different styles. He traveled to Edgefield, and trained under instructors such as Peter Lenzo and Justin Guy, the 2022 winner of the state’s Jane Laney Harris Folk Heritage Award. Like his instructors, Wright began to create face jugs, a tradition Edgefield is famous for, and transitioned to creating functional ware.

Wright is part of a Columbia folk art scene that is expanding, Orris said.

In alternative markets like Y’all-Mart and at the Noma Warehouse on Sumter Street, she has seen artists selling crochet pieces, ceramic art, artisan soaps and taxidermy.

“I think there’s a high demand for that” type of art and craft, Orris said. “People want to see something different when they go out to a market. And I’m happy that Columbia is starting to have more markets and more venues open to (hosting) markets.”

That could mean a promising future for art rooted in the past.

“It’s growing,” Orris said of the Columbia folk art scene. “It’s growing big time.”

Raine Orris sells her handmade animal bone jewelry almost exclusively at Y’all-Mart, an alternative market hosted at Columbia’s Art Bar. The market creates a space for arts and crafts that have unusual subject matters or materials.

Craig Watson has found success selling his homemade spices in places such as the Meeting Street Artisan Market. He’s dedicated to protecting the heritage of the craft and personal touches he adds to his work. But he would like to see his creations in brick-and-mortar stores one day and is looking forward to growing his business.

State of the Art Studio owner Levi Wright displays his face jugs alongside other S.C. folk artists. The bright colors and split faces are deviations from the traditional appearance of face jugs.

Wright keeps the tradition of folk pottery alive by giving others pottery lessons and sharing the history with people he meets. A student recently practiced using the pottery wheel with Wright at her side.