House Majority Leader Gary Simrill, R-York, said the Legislature wants the “most bang for the buck” for pay increases across the state.

The S.C Department of Corrections has started advertising for the first time with campaigns on TV, radio and billboards across the state.

Within the S.C. House office building, members of the Republican leadership work with the House Ways and Means to establish priorities for the 2018-2019 budget.

A correctional officer can be left alone at night overseeing 260 inmates.

A social worker can face more than 50 cases at a time.

A teacher can be driven away in one year by discipline issues and state testing requirements.

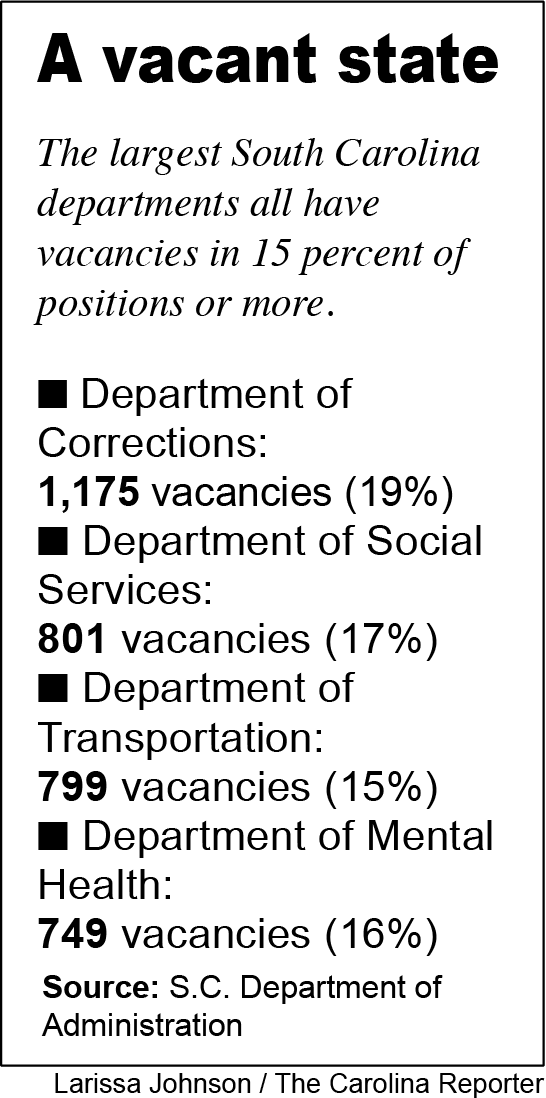

With wages that can’t compete against neighboring states and almost record-low unemployment in South Carolina, agencies are leaving positions vacant and perhaps jeopardizing state workers as well as some of the state’s most vulnerable citizens.

Almost 7,000 jobs are vacant in the South Carolina state government, and departments are looking abroad or to unusual sources for manpower.

But with demands on the 2018-2019 budget leaving less than ever for non-required increases, the House Ways and Means Committee has only included pay increases for specific positions.

“Everything we did was not something across the board,” House Majority Leader Gary Simrill said. “We actually looked within agencies to determine need.”

State-level government employees make 18 percent less than comparable jobs in the private sector and 15 percent less than comparable public jobs in other states.

Making matters worse, more than 10,000 state employees are at or reaching retirement age in the next five years — almost a third of the state’s entire workforce.

“Obviously there are plenty of needs in South Carolina,” Simrill said. “But employees are the human capital.”

While the raises to be introduced will help seven divisions, many of these divisions are facing vacancies numbering in the hundreds. To cope, departments and agencies across the state are looking to innovative staffing techniques, from international teachers to volunteer officers.

For teachers, low pay and little appreciation

“We’ve got ones from Jamaica, India, Romania, South America…” Jeffery Long, the director of certified employment services for Richland One school district, trailed off while trying to come up with the home countries of the 75 cultural exchange teachers working in his district.

In 2015, there were 430 teachers in S.C. schools from other countries on a short-term basis. Now, there are 546, with most teaching Spanish, math or special education.

Cultural exchange teachers are “not meant to replace traditional classroom teachers or teach on a permanent basis,” according to education department chief communications officer Ryan Brown.

But at Richland One, they help to fill the approximately 300 vacancies the district faces at the beginning of each year.

That’s high turnover for a district of 2,500 teachers, a problem reflected across the state. More than 550 positions were left open at the beginning of the 2017 school year after about 5,000 teachers left the profession for good.

“Part of it is a pay problem,” Brown said. “There’s a number of issues, but certainly pay is one of the easiest to address.”

In the House committee draft of the 2018-2019 budget, teachers will all get a two percent raise and the starting salary will increase to at least $32,000. That’s still less than South Carolina’s neighboring states: Georgia’s starting teachers earn at least $34,100, and North Carolina’s earn at least $35,000.

Long is skeptical that the two percent increase will make hiring any easier in his district.

“It won’t make any difference,” he said. “Because if they’re saying two percent across the board, all the districts are going to do the same thing.”

The real problem, according to Long, is the decreasing number of education graduates from colleges. Programs like referral incentives and a new $3,000 stipend for student teachers who commit to two years in the district are more critical to retention, he said.

The pay raise would be “a step in the right direction,” Brown said, but doesn’t address teacher’s concerns about state testing requirements and difficulties with classroom management. Both are frequently cited as reasons for leaving the profession. The department also requested an increase in per-student funding granted to school districts, but no increase is included in the House budget proposal.

Volunteers, cell phones and billboards

The first S.C. correctional officer from Puerto Rico is starting work soon. He’s worked in corrections before, and visited South Carolina in late February to go through his orientation. He’ll be back to the Palmetto State soon – the Department of Corrections covering his moving expenses.

The department has begun promoting in the unemployment-wracked U.S. territory to help fill its 640 vacant correctional officer positions.

Alongside the marketing campaign in Puerto Rico, the department has been running TV ads and taken out billboards, advertising not only for correctional officers but also for medical positions. Its marketing budget has shot up in recent years.

But the $750 pay increase included in the current House budget draft, which department director Bryan Stirling hopes will be increased in later drafts back to the $1,000 originally requested, could help attract more local workers to the department’s 21 facilities.

“Shortly after I first started, Walmart employees were making more money than a correctional officer in South Carolina,” Stirling said. Now, five years later, all are making at least $31,000.

Although starting pay has increased more than 10 percent in the past three years, 2017 was the first year since the recession that the department hasn’t seen falling numbers. While 640 vacancies is still almost a quarter of correctional officer positions, the number has gone down more than 100 since June 2017. Stirling partly credits new retention bonuses and changes in overtime pay for the decreasing vacancy numbers; this year, officers will receive more than $5 million in bonuses and $16 million in overtime.

But the vacancies have drawn the eye of the legislature because of a recent increase in violence. 2017 saw 37 assaults on staff by inmates – up from 21 in 2015 – and 12 inmates killed by other inmates, including four strangled to death in April in an unsupervised mental ward.

One reason for the increase in assaults, Stirling said, is an increase in covert phone use. The corrections staff can’t patrol the borders of every prison to stop phones from making it inside. Sometimes at night, there will be just one officer watching over up to 260 prisoners.

That’s where a program announced in late February comes into play – a volunteer group run by the governor, the S.C. State Guard, will begin a pilot program to monitor the borders of one facility, with the hopes of expanding to more. Corrections has been paying officers of the Richland, Lee and Berkeley counties sheriffs’ departments to help with external security, but volunteers from the State Guard are free.

But ultimately, volunteers, marketing and pay restructuring can’t make up for low pay, Sterling said.

“The difficulty is…”

While large departments might be suffering from hundreds of vacancies, many smaller agencies can face a big detriment with just a single unfilled position. And those agencies aren’t likely to see any increase in pay from the state Legislature.

The Art Commission has 14 out of 25 positions filled. The Confederate Relic Room and Military Commission has five of nine. The State Ethics Commission has 12 of 16, and one of the vacant positions is its only lawyer.

But the raises included in the budget, according to Simrill, are the ones most needed by the state.

“You can do across the board a little bit for everybody,” he said. “But what we’re trying to do is bring the others up to parity to make sure that we have employees where we need them.”