Since 2006, David Shields, a professor at USC, has been on a scavenger hunt for more than 40 heirloom ingredients for Lowcountry cooking.

Sometimes it was luck and sometimes it was “real historic ingenuity” for David Shields as he embarked on a mission to bring heritage foods back to Columbia.

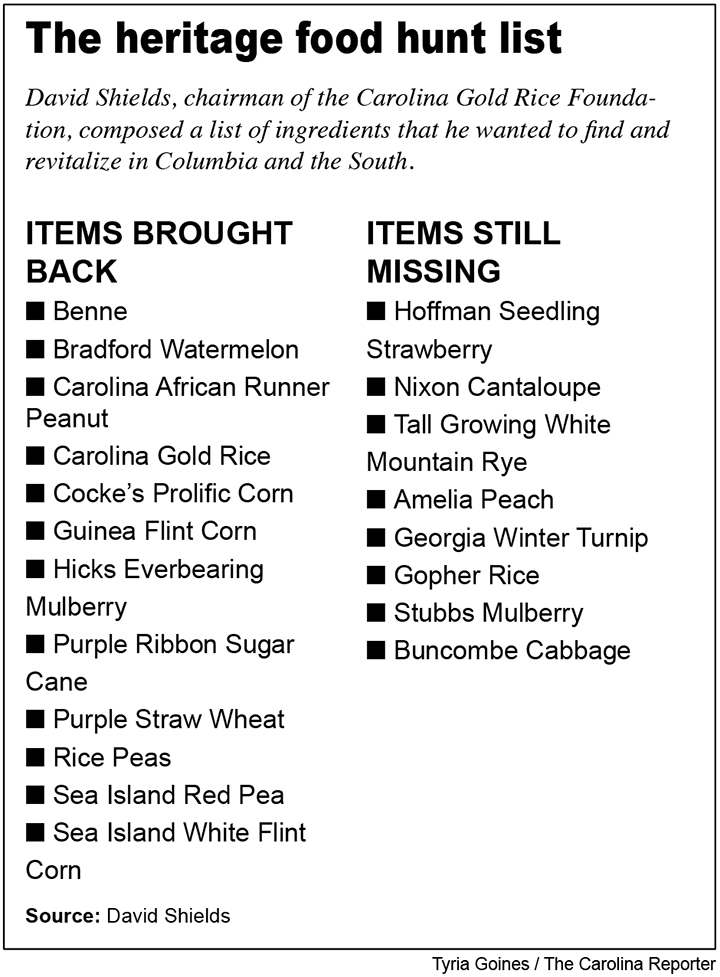

Shields, a professor at the University of South Carolina, is chairman of the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation, an organization dedicated to bringing back grains and heritage vegetables that have disappeared from modern food life. In 2006, he created a list of about 45 key ingredients for Lowcountry cooking. It turned out that all of those ingredients were functionally extinct according to Slow Food’s Ark of Taste, the global register of endangered foods.

“One of the problems is you have to know something is lost before you find it,” Shields said. “By the 1990s, the loss of the traditional food crops in the South had gotten so gray that the people didn’t even know what they had lost. Amnesia had set in.”

In the process of revitalizing the heritage ingredients, the first thing Shields and his team did was research what was lost. They made the list and sought to track every ingredient on that list. In the past 12 years, around 30 classic ingredients have been brought back and there are about 15 more that are in the process of revitalization.

“Sometimes it was through luck, sometimes it was through real historic ingenuity,” Shields said. “Sometimes stuff was preserved under seed banks, but with other names. Sometimes we’re driving along the road and we see corn growing. But we want to find them all.”

HERBEMONT GRAPE

“These grapes are particularly interesting because the story of American winemaking is something that most people think is centered in California, New York and places like that.”

In actuality, Shields said, “the first regularly offered vintage wine of any quality came out of Columbia in the 1810s and 1820s.”

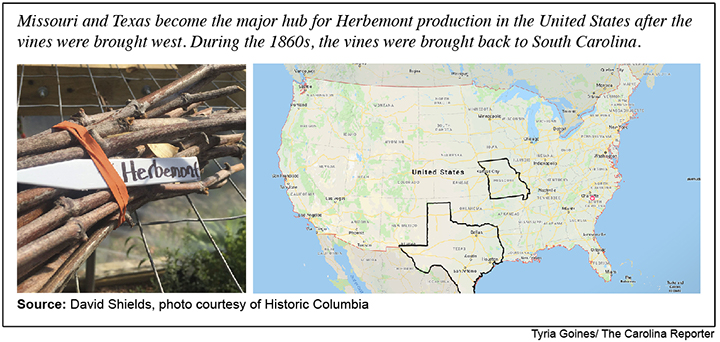

Nicholas Herbemont, a former French professor at USC, produced the grape through experimentation in a block-sized vineyard on Gervais Street. He managed diseases that bedeviled winemaking in the previous hundreds of years.

People had been trying to make wine using European grapes that were brought across the Atlantic since the founding of Jamestown, Virginia in 1607. However, there was a problem with the multitude of native grapes already existing there. The native grapes would send out pathogens that would kill rival grape varieties, which caused the European varieties to die after one or two years of cultivation.

Herbemont managed the major maladies that prevented winemaking using a grape that was a cross between a European grape and a native grape, one with the native pathogen resistance and European flavor.

In the 1860s, a root disease moved to Europe and threatened the wine industry which caused all of the Herbemont grape plants in the country to be uprooted and shipped to Europe. While the Herbemont grape has been revitalized since the mass uprooting, it is mainly grown in Texas and Missouri.

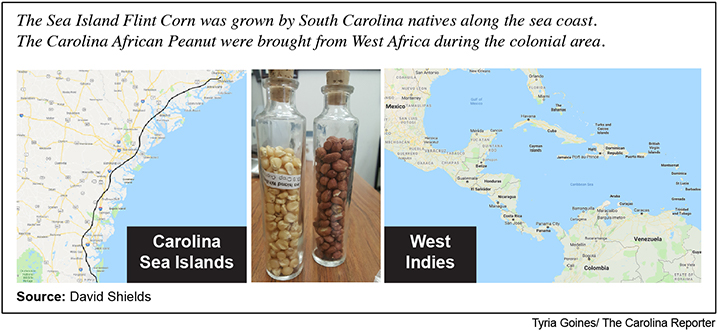

SEA ISLAND FLINT CORN

This white flint corn is a variety that was grown by South Carolina natives along the sea coast. A problem with growing corn by the sea coast is corn weevils. If there is a soft surface around the corn, the weevils bore into the interior and suck out all of the starch. Weevils can reduce the insides of softer corn to dust.

“However, the hard kernel varieties such as the flint corn are too tough in their surface for the weevils to get through, so they thrive,” Shields said. “It’s very good to make grits, if you like white grits. But if you prefer yellow grits, there’s a million great varieties as well.”

CAROLINA AFRICAN PEANUT

“These are the ancestral peanuts of the South,” Shields said. “They are also sweeter; even though they are raw you can eat them and taste its quality. The quality in taste is the thing that makes it worth bringing back.”

The Carolina African peanuts were brought from West Africa during the colonial era. They are smaller and darker in color than traditional Virginia peanuts. These were the original peanuts that were used to make boiled and roasted peanuts in the South until the 1840s.

“If you want peanuts in candy, this is your peanut. But it ceased being grown because its smallness makes it difficult to harvest with a mechanical harvester. And it stopped being grown as a crop in the 1930s.”

Shields thought the peanut plants were extinct, but seeds were preserved by peanut breeders at North Carolina State University. Three years ago, 5 million seeds were dispersed among various growers cross the South to begin growing again.

CAROLINA GOLD RICE

Rice was the first thing that Shields brought back through the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation.

Carolina Gold Rice, a long grain with a rich, starchy texture was once a staple of Southern cooking. It’s considered the grandfather of long grain rice in the Americas and became a commercial staple of the coastal lands of the Carolinas in 1685.

The rice was first produced in the wetlands of South Carolina before being planted throughout the South and exported worldwide by 1800. The rice remained prominent into the 20th century until new varieties rose after the Great Depression.

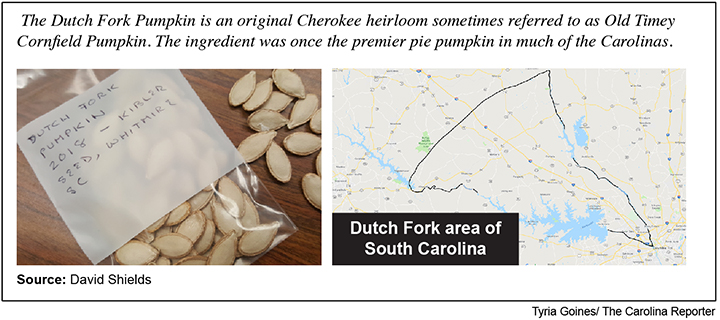

DUTCH FORK PUMPKIN

Cucurbita moschata, or the Dutch Fork Pumpkin, is an original Cherokee heirloom sometimes referred to as Old Timey Cornfield Pumpkin. The ingredient was once the premier pie pumpkin in much of the Carolinas. Over time, it has become extremely rare, and has only been grown by a handful of farmers in South Carolina in the past 100 years.

“If you like chewy pumpkin pies or roasted pumpkins, this is a wonderful pumpkin to use,” Shields said.