University of South Carolina officials followed the letter of the law in their handling of the disappearance and murder of student Samantha Josephson in March, according to a campus safety expert.

Laura Egan, senior director of programs for the Clery Center for Security on Campus, said USC was compliant with the Clery Act, the federal legislation that governs the reporting of crime on college campuses, in not including the Josephson case in the school’s daily crime log.

Josephson, a 21-year-old senior in the school’s political science program, was last seen after 2 a.m. March 29 after getting into a car police believe she thought was her Uber in the Five Points entertainment district of Columbia. Her body was discovered later that day by hunters in a wooded section of Clarendon County, about 65 miles southeast of Columbia.

Kidnapping is not a crime schools include in their crime logs and crime statistics under Clery, according to Egan. Since the body was found outside of USC’s Clery jurisdiction, the school could actually be penalized by the U.S. Department of Education for “over-reporting” if they included the murder in its Clery crime report, issued each October.

“There isn’t an ‘if it’s close, count it’ mentality. They don’t allow that,” Egan said.

Although the Clery Center provides guidance to and resources for schools, the U.S. Department of Education oversees the mandatory reporting of crime statistics under the Clery Act. Both the center and the law are named for Jeanne Clery, a Lehigh University student who was raped and murdered in her dorm.

USC spokesperson Jeff Stensland said in an email that the school has verified that the Josephson case is not a “required reportable crime under the Clery Act.”

The school could acknowledge the kidnapping and murder as a “caveat” to their report, a kind of footnote to the statistics noting that the incident occurred, Egan added.

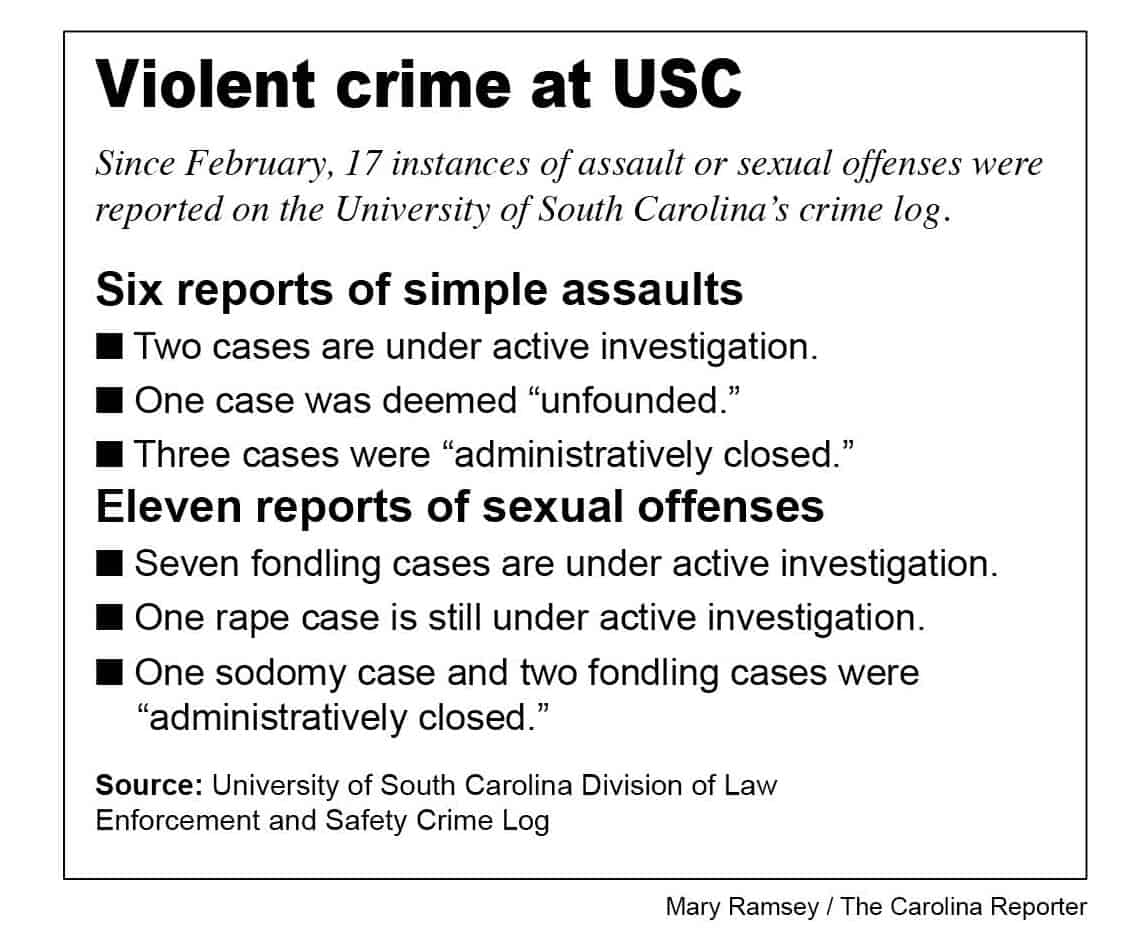

In the wake of Josephson’s disappearance, USC’s Division of Law Enforcement and Safety issued a crime bulletin, which officials define as a notification sent when “a situation or incident is not immediately life threatening or is contained.” Crime bulletins are posted on the Division of Law Enforcement and Safety’s website and posted to its social media accounts.

The suspect in Josephson’s disappearance and murder, Nathaniel Rowland, was still at large at the time the bulletin was posted. Josephson’s body had been recovered by that time but her identity had not been confirmed and she was still considered a missing person.

USC did not send a Carolina Alert about the Josephson case. Carolina Alerts are sent to students, and often their next of kin, through text message and email.

Egan said most schools have “tiers,” like Carolina Alerts and crime bulletins, to their emergency alert systems. It’s up to individual schools, she explained, to decide how many tiers and what the criteria is for them.

The Josephson crime bulletin is no longer listed on USC’s Division of Law Enforcement and Safety’s website.

“I don’t know why the bulletin is no longer posted,” Stensland said.

Egan said it’s important for schools to communicate clearly and quickly about crimes that happen in popular entertainment areas nearby to campuses. Five Points is within walking distance of campus and a favorite spot for hundreds of students, so students should know who to go to if they experience safety issues there, she said.

“One of the first things we always tell campuses is to make sure they are being open and communicating with their campus community about the extent to which they can be a service if someone is in trouble,” she said.

In addition to transparency and communication, Egan said the Clery Center advocates for schools to continuously review and improve their safety procedures. The Clery Act mandates that schools provide an overview of their safety initiatives in their annual Clery report.

That part of the report, as well as other public communications, is a place for USC to include and discuss the Josephson case, according to Egan.

“It’s helpful to remember that the [Clery report] isn’t the only way for a campus to communicate about safety and statistics,” she said.

The Josephson incident resulted in a flurry of safety proposals in the Legislature and by city officials, USC, Uber and local businesses.

A bill to mandate that rideshare drivers display illuminated signs in their vehicle while working moved quickly through the House and was revised in the Senate to instead mandate that drivers display their license plate numbers on the front of their cars.

Two senators, Sandy Senn, R-Charleston, and Dick Harpootlian, D-Richland, introduced a concurrent resolution to “urge local governments, municipalities, law enforcement agencies, colleges, and universities to accelerate their efforts to improve the safety of transportation network companies and ride-hailing services.”

At the city level, Mayor Steve Benjamin proposed a new requirement for rideshare vehicles to undergo a city inspection. He also called for more designated pick-up areas and better lighting at existing pick-up spots, among other ideas.

USC is partnering with Uber to improve safety features within the Uber app.

Bar owners in Five Points have also agreed to let their door staff work on the streets in the hour after the bars close to escort customers to their rideshares, help verify rides and look out for suspicious activity.

USC officials “have not taken a formal position on particular legislation, but have expressed a strong desire for increased rider education as well as support for a designated rideshare pick-up point in Five Points,” according to Stensland.