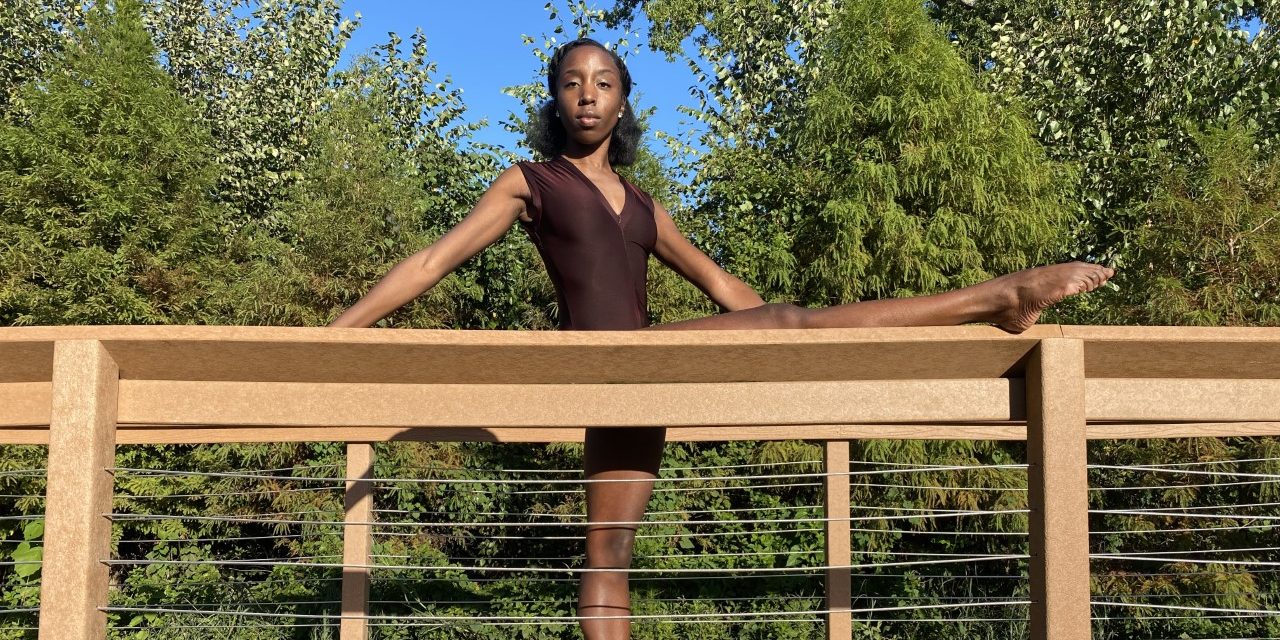

Trinity Cox, a dancer for Columbia City Ballet, said she has to think about more when dancing ballet as opposed to other dance styles but that it’s fulfilling to her. (Photo by Shakeem Jones)

Trinity Cox was told by her teachers she was born to dance, so she took a dance class at her high school.

At first, she hated it – it was rigorous and hard on the body. But one day, she walked into her dance teacher’s office and saw the teacher’s internet screen.

“I remember seeing the words “Black” and “ballerina,” Cox said.

“It was when Misty Copeland first broke out,” Cox said, referring to the trailblazing Black ballerina of the American Ballet Theatre in New York City. “She was super young. She had her bangs, she had on a red leotard. That’s when I was like, ‘Whoa, I can do this.’ And it morphed into a love.”

But Cox also said she was bullied at her high school – to the point where she decided to transfer. Her dance teacher didn’t take the news well.

“I guess she didn’t like the fact that I was leaving, so it went from her loving me as a student to her not caring to nurture me anymore,” she said.

The conversation was especially hurtful to Cox because ballet was already was difficult for her. And she knew she was in an art form that historically was not accepting of minorities.

RACE DISPARITY

As a Black ballerina, Cox knows she’s not alone.

Minority advocates for ballet are pushing for more inclusion and diversity in ballet, which has long had a reputation for being entertainment exclusively for society’s elite. For Columbia’s ballet community, the conversation hasn’t brought much visible change.

Ballet originated in the 15th century during the Italian Renaissance. By the 1800s, Russia had become a leading center for the dance form, a reputation it still holds today. In Russia, ballet showed women as heroines with fairy-like characteristics of purity and goodness, according to the Atlanta Ballet’s website.

Ballet made its way to America only recently, when Russian Choreographer George Balanchine relocated to New York City and co-created The School of American Ballet in 1934. Then, in 1948, he co-founded the New York City Ballet.

Arthur Mitchell, a protégé of Balanchine, became the first Black principal dancer at the New York City Ballet in 1955. But he was an exception. Few Black ballet dancers could find work.

So in 1969, Mitchell founded the Dance Theatre of Harlem. University of South Carolina dance instructors Thaddeus Davis and Tanya Wideman-Davis, a husband and wife duo, each spent time dancing for the Dance Theatre of Harlem.

“Mitchell started the company after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, and he was a derivative of the Harlem neighborhood,” Wideman-Davis said. “He started the Dance Theatre of Harlem because people were not hiring Black dancers.”

Wideman-Davis said the company became a beacon for Black dancers around the world – what she called a “Black diasporic center.”

“There were dancers from England, France, Venezuela, Brazil,” Wideman-Davis said. “All over the world, black dancers were having a problem getting hired at ballet companies, so they would come to New York to dance with Dance Theatre of Harlem.”

Despite the efforts of Mitchell and others who came after, Wideman-Davis said there is still a race disparity in ballet – especially for Black women.

“Black women, or really women who have a hue that quite possibly could look like they are of African descent — have not previously had access because ballet is all about preserving white female docility, and our bodies kind of challenge that,” Wideman-Davis said. “So when you’re thinking about why we have not had access to that form, it’s just simply because it’s been run and it has been produced by white people who are interested in seeing themselves.”

Aside from racial disparities in ballet, Jennifer Deckert, associate professor of dance at USC, said industry professionals in power who can make changes should be held accountable.

“I think a lot of times it’s difficult because the form is connected to the hierarchical structure which exists within classical training,” Deckert said.

She said it’s typically white men at the top.

Davis agrees. “You have to look at where the decisions are being made. Who’s on the board (of directors), and how could shifting the demographics on the board of directors shift the demographics in leadership, which would shift the demographics that we see on stage.”

Cox, who is in her second year as a dancer at the Columbia City Ballet, said she has experienced the discomfort of being the only black woman in a ballet company.

“You would think that because we all live in America that of course you’ve seen Black people before, right?” Cox said. “But there’s this weird, odd energy that can somehow bubble up because you look different from everyone. But it’s also weird because it isn’t something that you can change.”

She said the initiatives for diversity in ballet don’t always appear to be coming from an authentic place.

“It’s like they’re trying to create the diversity, but when you do that, you aren’t being true, and in turn you are disrespecting the art form,” Cox said. “I don’t want you to choose me if I don’t need to be chosen. … Don’t just pick someone because you need someone who’s black. Be true to the art form.”

BODY TYPES

Helping dispel the industry’s reputation as exclusive is the Columbia Repertory Dance Company, which fuses ballet and contemporary dance.

Founded by Stephanie Wilkins and Bonnie Boiter-Jolley, Boiter-Jolley said she and Wilkins created the group to provide professional dancers with alternatives outside of major dance groups in the city.

Boiter-Jolley said she loved the way Wilkins leads in choreography.

“I really love the way that her work shows human emotion as opposed to it just being about how much can you point your feet and how straight can your knee be,” Boiter-Jolley said.

Wilkins grew up dancing in ballet classes. But she also attended summer dance camps, where she was exposed to modern and contemporary dance.

“I was, like, this is more suited toward me because I’m not like a skeleton,” Wilkins said.

“I’m muscular and athletic looking,” she said. “You really had to be that stick figure to be a ballet dancer. I was tiny in high school, but I knew that I was tall and that was also kind of an issue in ballet. … It wasn’t as inclusive back then. Dance doesn’t have to have a size. It doesn’t have to have a gender. It doesn’t have to have a sex or an orientation or whatever. If you can move and if you are a beautiful mover, it does not matter.”

She believes things are improving generally in ballet.

“I mean, now in the ballet world, it’s completely cool,” Wilkins said. “Ballerinas are taller, and they don’t look like they’re starving to death.”

But Wilkins and Boiter-Jolley said there’s still progress to be made in Columbia.

“It’s still not quite there yet. … “I’ve always felt a little uncomfortable,” said Boiter-Jolley, who grew up dancing in Columbia. “I’ve always been made to feel a little bit self-conscious.”

Cox reflects on the joys she’s had in her career, such as having moments with legendary ballerinas she has looked up to, including Raven Wilkinson, the first African-American woman to dance for a major classical ballet company. Cox also had a full-circle moment. When attending a performance at the American Ballet Theatre, she met Misty Copeland.

“These moments have crafted my mind and put me in this bubble of just knowing that, ‘Trinity, not only what you are pursuing is more than possible, but you are going to be beyond what you ever imagined,’” Cox said.

Cox said she has felt the comfort of dancing where she was in the majority, as well as the discomfort of being in the minority. (Photo by Shakeem Jones)

Columbia Repertory Dance Company’s roster showcases diverse bodies, races and genders. (Photo courtesy of Columbia Repertory Dance Company)

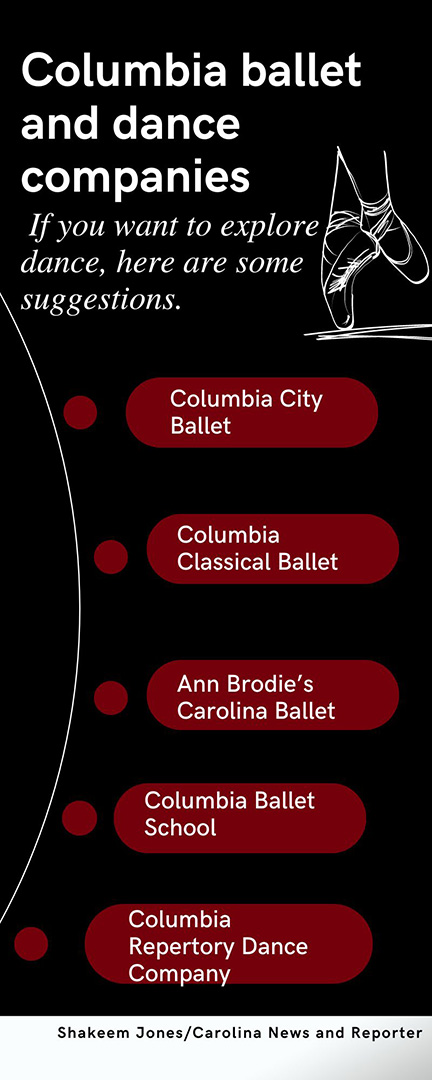

A small selection of local dance companies that specializes or covers ballet. (Shakeem Jones/Carolina News and Reporter)

Cox, a dance instructor, said she wants to inspire all little girls to achieve their dreams. (Photo by Shakeem Jones)

Body and age diversity are on display during a recent performance of the Columbia Repertory Dance Company. (Photo courtesy of Columbia Repertory Dance Company)