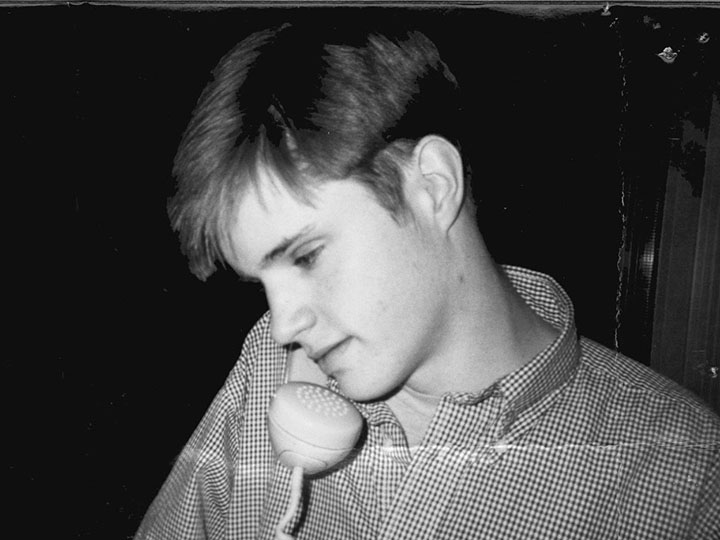

Photo provided by The Matthew Shepard Foundation via AP

Twenty years after his horrific death, Matthew Shepard, a young gay man whose name became synonymous with hate crime, was finally laid to rest on Friday at the Washington National Cathedral.

For one South Carolina man that symbolic gesture of hope resonates in the LGBTQ community, but he believes there is still more work to be done to combat crimes based on sexual orientation.

“There are parts of the LGBTQ community still facing violence and being murdered at alarming rates,” Travis Wagner, an associate professor in University of South Carolina’s Department of Women’s and Gender Studies, said. “As we’re understanding that things have changed, we should also be having conversations about who this is still happening to. I’m worried that that’s going to get lost.”

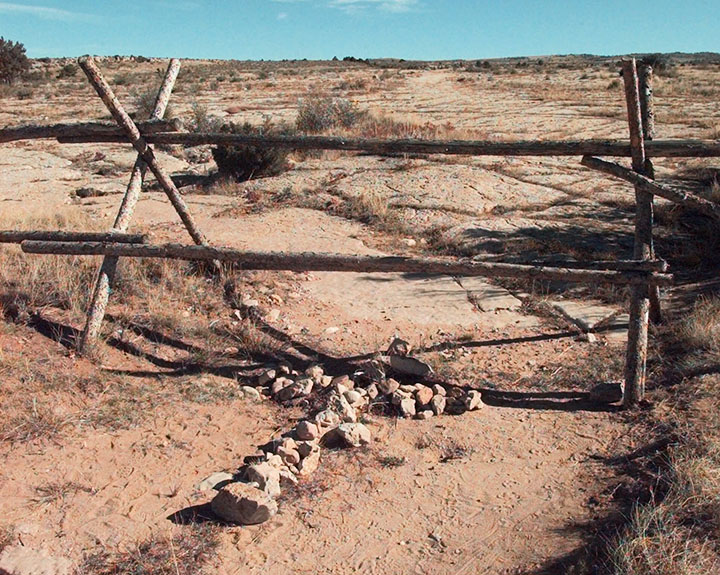

On the night of October 12, 1998, 21-year-old Shepard was the victim of what is now described as a hate crime by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He was robbed, beaten and tied to a fence in Laramie, Wyoming by two men for allegedly being openly gay. After 18 hours in near-freezing temperatures, Shepard was found by a cyclist who at first believed that he was a scarecrow. He died five days later.

“This happening at a church in Washington right now really means something,” said Wagner. “That’s not a universal experience, but that it can happen on national grounds really means something.”

Wagner also wants people to realize that, while celebrating this moment for Shepard, it’s important to not forget about what is still happening in the LGBTQ community.

“This is still a time that we have to be more active to ensure that we’re more inclusive in advocating for their needs right now.”

Bishop Gene Robinson, the first openly gay Episcopal bishop and a close friend of the Shepard family, played an essential role in having Shepard’s internment at the cathedral.

“For Matthew to come home to the Episcopal Church of which he was a part and for the LGBTQ community far and wide to see a church welcoming him home to rest there in the cathedral forever is a huge statement,” Robinson said in an interview with NPR.

At the time of Shepard’s death there were no hate crime laws active in Wyoming, so his two murderers, Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson, were both convicted of first-degree murder and are each serving two consecutive life sentences.

For personal reasons, Shepard’s family decided not to bury him traditionally in a cemetery and instead had him cremated.

“We didn’t want to open up the option for vandalism. So, we had him cremated and held onto the urn until we figured out the proper thing to do,” the family stated in a press release. “We’d been looking for the just the right place to finally put Matt to rest, and we think this is the perfect fit and the perfect time.”

They went on to say how meaningful this moment is for them and all of the people who knew him.

“The visibility of it (Shepard’s death) at the time was a major shift in how we understood and talked about LGBTQ representation in the nation,” said Wagner. “This happened constituting a hate crime to the point that it led to legislation being brought forth to try to attend to this not happening again.”

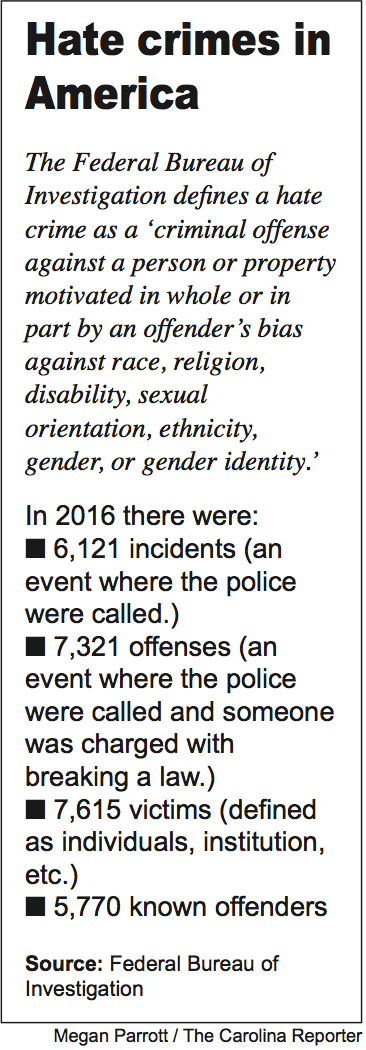

In 2009 President Barack Obama signed into law the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act in an effort to help better define and enforce hate crime laws.

Byrd was an African-American man who was killed the same year as Shepard after he was dragged behind a pickup truck by three white supremacists in Jasper, Texas.

“I think it will bring a sense of safety as well as closure for the Shepards who really turned this act of violence into an amazing campaign on behalf of gay and lesbian, bisexual and transgender young people everywhere,” said Robinson.

In a statement, the Washington National Cathedral said that while Matthew died far too young, his death “gave life to a new generation of activists and allies who are committed to proclaiming God’s love for all of God’s children – no exceptions or exclusions.”

Shepard’s service at the cathedral was open to the public and live-streamed online. After the service, his ashes were placed into the crypt in a private ceremony.

“For the past 20 years, we have shared Matt’s story with the world. It’s reassuring to know he now will rest in a sacred spot where folks can come to reflect on creating a safer, kinder world,” Matthew’s family stated in a press release. (Photo provided by The Matthew Shepard Foundation via NPR)

Shepard’s remains will be interred in the cathedral’s crypt with the likes of President Woodrow Wilson, Helen Keller, and Keller’s teacher Anne Sullivan. (Photo by Getty Images via NPR)

After being beaten, Shepard was tied to this fence and left to die. Bishop Gene Robinson said in an interview with NPR that, “My hope is that it will be a constant reminder that this work isn’t done. We’re not talking about things that happened only 20 years ago, but actually continue to happen.” (Photo via AP)