Justice Jean Hoefer Toal poses in her backyard in Columbia with a structure mimicking a 1988 editorial cartoon about her position as the first female South Carolina Supreme Court Justice. Photos by: Rachel Strieber

“If you get a little something and start moving up, keep the ladder down, and pull your sister along.”

Retired South Carolina Chief Justice Jean Hoefer Toal calls that “Toal’s Ladder Principle,” powerful advice for young women she shared as she sat in her back yard last week and reflected on her monumental contributions to the legal field.

“It’s mighty tempting if you’re in the minority and you’re the one singled out, and you get a little something in life, to kind of hold it close, because there’s not enough to go around,” said Toal, 77, who broke barriers as the first woman to serve as a South Carolina justice and chief justice. “But what you should be doing is leaving the ladder down and pulling those behind you up.”

Born on August 11, 1943, Toal became active in civil and women’s rights at a young age.

“This was a time of rigidly enforced, by law, segregation in the South, and certainly in South Carolina,” said Toal. “It affected everything that a person of color could do.”

Toal was 11 years old when the U.S. Supreme Court decided the historic Brown v. Board of Education school desegregation case. This decision, which incorporated the South Carolina Briggs v. Elliott case out of Clarendon County, ruled racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional. When she saw news of the decision – reported on the very new media called television –she questioned the negative press the decision was receiving.

“I thought to myself, ‘Why is it we have to be separated? Why can’t everyone go to school together?’” said Toal.

When she entered high school and became more politically active, she voiced stronger opinions against segregation. During Toal’s senior year, she wanted to participate in a student march for the end of segregation in downtown Columbia.

“They told us white kids… that they thought it was pretty dangerous and provocative if we took part in it,” said Toal. “So I watched.”

Toal said that 187 Black students, including Rep. Jim Clyburn, D-S.C., who was then a student at South Carolina State, were arrested for breach of the peace and put in jail. They were tried in the Richland County courthouse, where the students’ lawyers contended the students were denied their First Amendment rights to assemble peaceably.

“I went. I skipped school one day and went with some of my buddies, and we sat up in the balcony, which was required seating for Black people – they couldn’t sit down on the floor,” said Toal. “We sat up there in the gallery and watched the trial… and it was amazing.”

Matthew Perry, the students’ chief lawyer, made it clear that the marchers were not the ones breaching the peace. Despite his arguments, which Toal highly regarded, all of the Black students were convicted.

“That case ultimately made its way to the United States Supreme Court… Edwards v. South Carolina,” said Toal.

In 1963, the Supreme Court ruled that the state had violated the students’ First Amendment rights.

“[I] had the good fortune to have my eyes open at a young age to what has become one of the things I care about deeply – which is racial equality and equality of opportunity for all people,” Toal said. “And I devoted a lot of my adult life to those issues.”

When Toal went to Agnes Scott College in 1965, she dealt with another timely issue: women’s rights. The concept of going to law school was not promoted to women at all. However, her friend’s father, who was a judge, persuaded Toal to take an undergraduate constitutional law course at Emory University.

“Well, I took that course. Oh, I wasn’t in that course but weeks, and I said, ‘This is what I want to do,’” said Toal.

In 1968, Toal graduated law school as one of only four women at the University of South Carolina School of Law. She said that only around 10 were actively practicing law in South Carolina at that time, so women made up significantly less than 1% of practitioners nationally and in the state.

“The world has changed since then, and I think women’s attitudes about what their horizons can be have changed dramatically,” said Toal.

Toal practiced for 20 years before being elected to the South Carolina Supreme Court.

She encourages people now to look at each other as colleagues rather than with gender-based assumptions.

“My brothers in the practice were some of my most loyal supporters who helped me out and helped me over the bumps and looked with disdain on those who had old-fashioned assumptions about what women could do,” said Toal.

Toal often talked with Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and her good friend, the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, about how their initial experiences were similar. The horizon for jobs was very limited for women, she said.

“I was told, ‘You know, we might find something in the probate, the property section, but we’re really not hiring women,’ as if that should be understood by everybody,” said Toal.

In 1970, Toal brought a case for a female University of South Carolina law student, Vickie Eslinger, who had been offered a job as a page for the South Carolina Senate. When Esligner went to take her place, the clerk of the Senate told her that women were not allowed to serve as pages.

In the lawsuit, the state’s defense was that female pages might compromise the senators’ morals, because the job entailed pages bringing official papers to the senators’ hotel rooms at night.

“So I said, ‘We’ve got to find someone who knows something about this gender discrimination.’,” said Toal. “So I got the word that… a young woman was heading up something called the National Center for Women in the Law, and her name was – Ruth Bader Ginsburg.”

Toal called her asking for assistance in the case, and Ginsburg developed the argument against the state. Eslinger lost in the district court, but the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals later reversed, and she won the case.

After that case, Toal would routinely take South Carolina female lawyers to be sworn in at the U.S. Supreme Court, and they would often meet with Ginsburg.

“Whenever I’d see her, she’d say, ‘Now, how’s our client, Vickie?’” said Toal.

Toal said that although the Equal Rights Amendment was never passed, she thinks the debate over a woman’s place in the law propelled many breakthroughs for women.

“So, change can sometimes be effective even if you don’t win the case, but if you win the public opinion and if you raise people’s consciousness about what they should be having, and women definitely have had their consciousnesses raised.”

In addition to being the first female, Toal is also the first Columbia native and Roman Catholic to serve on the state’s highest court. She served on the court for 27 years, with 15 of them as chief justice, retiring in 2015 at the mandatory retirement age of 72.

Abbeville County School District v. South Carolina, which spanned over 20 years, is a case that stands out in Toal’s career. This case involved eight South Carolina school districts claiming the state failed to meet a constitutional obligation. The schools argued for the state to provide a system of free public schools that offer the opportunity of a “minimally adequate” education.

“The promise of Abbeville is unfulfilled, but we’re getting there,” said Toal. “And it certainly emphasized the disparity, which we held was an unconstitutional disparity… I do think there is much more conversation now starting to develop.”

Toal’s accomplishments extend outside of the courtroom as well. She said the biggest achievement of her career was modernizing the automation of court records and proceedings.

When she became the chief justice in 2000, the administration of courts was manual and all on paper. Toal hired a professional from the education field to assist in developing an automated system.

“All wisdom does not reside in lawyers,” said Toal. “I wanted somebody as my IT director, who had had some experience in a more modern approach to communication and record-keeping… It was called the internet.”

This decision brought connectivity to the smallest communities in South Carolina and started at the lowest level of courts. The system was then adopted around the country.

“That’s the paradigm now – that’s how we automate…,” said Toal. “I am proudest of that for what it did for South Carolina as well as for the influence it had around the country.”

Becoming and maintaining the position of chief justice provided some challenges for Toal.

“There had never been a woman on the Supreme Court…,” said Toal. “It was a mountain to climb for everybody to get used to the idea that a woman in her 40s – when everybody else who had ever been elected to that court had been men in their 50s or 60s – that someone young and a woman would be an appropriate member of that five-member court.”

Toal’s position and longevity on the court changed the standard for women’s career goals.

“The lift I gave women and the encouragement I gave women to dream high and shoot high for what they wanted in the legal system was a big positive of my being on the court,” said Toal.

Toal’s family, including her husband Bill Toal and two daughters, supported her throughout her legal and legislative accomplishments. She said they are the reason she stayed grounded to Columbia, even when offered job opportunities by President Jimmy Carter.

One person, in particular, inspired her most.

“The best lawyer and the most respected lawyer that I’ve ever come in contact with is the one I’ve been married to for 53 years,” said Toal. “We were a team, and that team helped me succeed.”

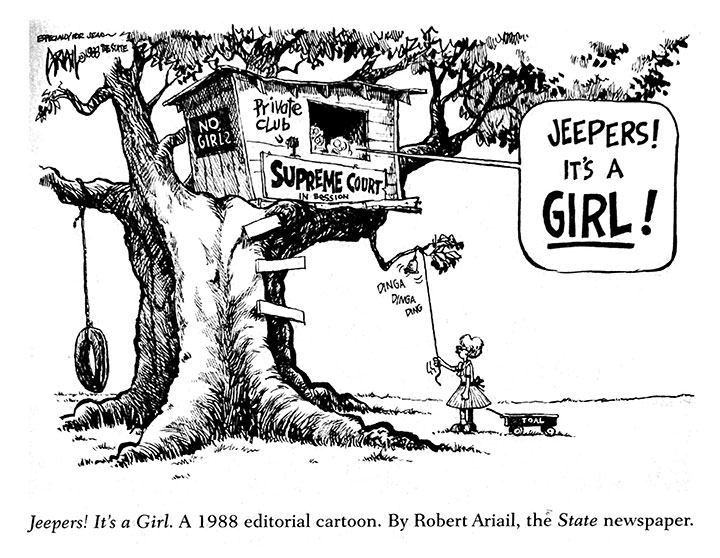

This 1988 editorial cartoon by Robert Ariail, which appeared in The State newspaper, symbolized the monumental achievement of Justice Toal joining the South Carolina Supreme Court.

Justice Toal explains the meanings behind many of the cartoons the press published about her throughout her career. She framed many of the editorials and have them on display in her home in Columbia.

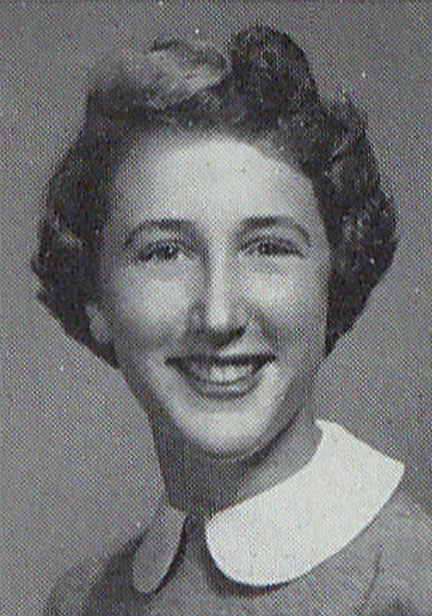

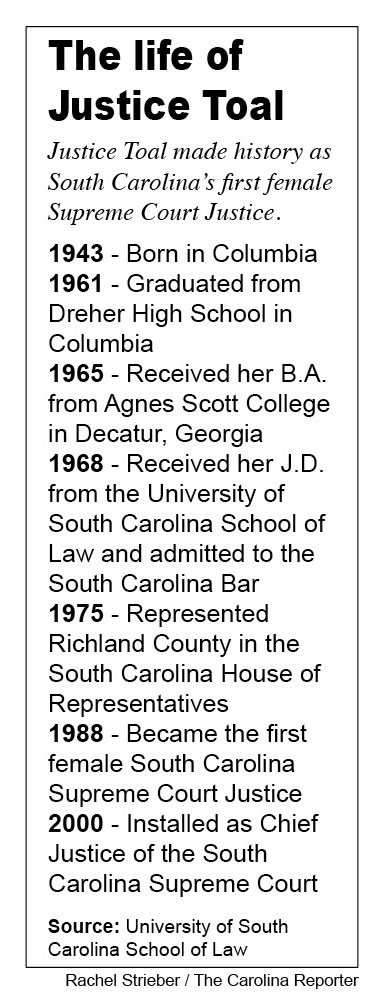

Justice Toal graduated from Dreher High School in 1961. She went on receive her B.A. from Agnes Scott College in Columbia. Photo courtesy: Yearbooks of Columbia Area Schools Collection, Richland Library

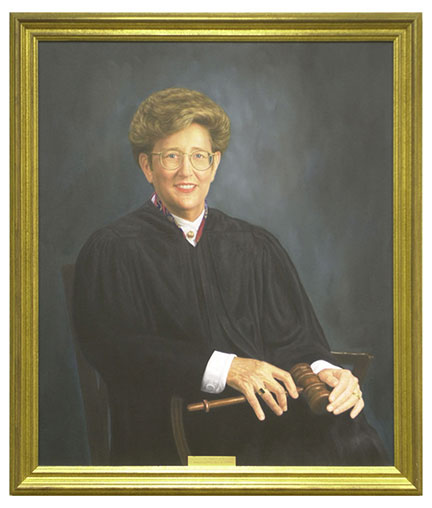

A portrait of Justice Toal is on display in the Reading Room at the University of South Carolina School of Law, where she received her J.D. in 1968. Photo courtesy: University of South Carolina School of Law

The American flag waves in front of Justice Toal’s home. Born and raised in Columbia, she remained working in South Carolina throughout her legal career to remain close to her family.

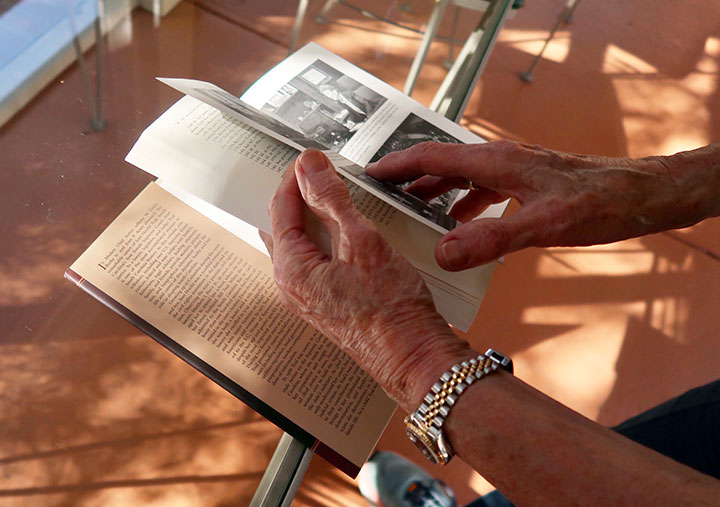

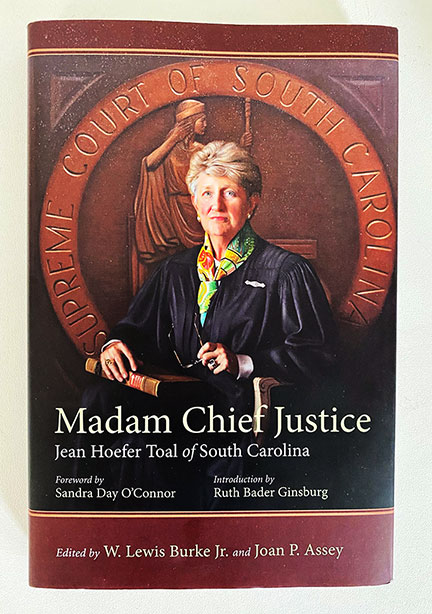

Justice Toal flips through a book with a collection of essays about her career as Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court.

Sections of “Madam Chief Justice” were written by Justice Toal’s family members and “good friends,” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

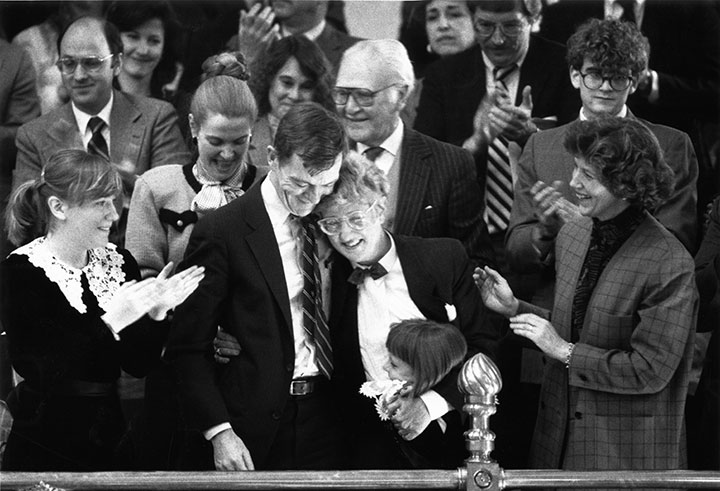

Justice Toal celebrates her election to the South Carolina Supreme Court in 1988 with her husband, daughters and other friends and family members. Photo courtesy: The State Photograph Collection, Richland Library