This opossum at the Carolina Wildlife Center suffers from leucism and lacks the amount of fur needed to withstand the winters in South Carolina. Leucism is similar to albinism with the notable exception of pigment in some areas like eyes.

The Carolina Wildlife Center has been serving sick, injured and orphaned animals of the Midlands for almost three decades. The non-profit organization began in a garage with five volunteers and has now grown to a organization that assists nearly 3,400 animals a year. But the Wildlife Center has outgrown its facility and is looking for an upgrade.

South Carolina has been rapidly growing in the past few decades, and as more people move to the Palmetto state the natural habitats of native wildlife is encroached upon leading to more encounters between animals and mankind.

“The best thing we can do is teach everybody how to interact with these animals so they don’t end up in situations where they are injured or in distress, ” Jay Coles, executive director of Carolina Wildlife Center, said. “That would significantly reduce what we do here to the extent where we wouldn’t have to exist.”

Many of these encounters often leave the animals injured or killed. In South Carolina, there are only six species of snakes that are venomous; however often non-venomous species are killed on sight due to misidentification or fear.

The Carolina Wildlife Center is attempting to assuage the general fears and misconceptions of native wildlife by visiting local schools as part of their community education program. Coles believes that education is critical in wildlife conservation.

The education program visits 40 to 50 school groups a year and hosts public events for civic organizations to teach locals about the animals that live alongside them. Helen Dyer, Carolina Wildlife Center operations and volunteer coordinator, believes that teaching young children about wildlife is key to protecting animals.

“If we can develop a love and respect for our wildlife at a young age then there is hope for the future,” Dyer said. “They’ll grow into adults that will appreciate and help protect these animals.”

Currently the center is home to several hundred squirrels that were orphaned during the late summer breeding season and dozens of reptiles ranging from turtles to timber rattlesnakes. The center maintains an avian section for raptors and water fowl. The center takes in around 1,000 birds during the summer mating season from hatchling to fledgling and maintains a strict feeding schedule that demands feedings in some situations every 15 minutes from sunrise to sunset.

“The ultimate goal for every animal that comes through these doors is that it be released back into the wild into a native habitat suitable for its survival,” Coles said.

Some animals are unable to be released into the wild after treatment. One opossum who was brought into the center suffers from Leucism, a disease similar to albinism that leaves the animal partially hairless, and cannot be released because it will not survive a cold winter.

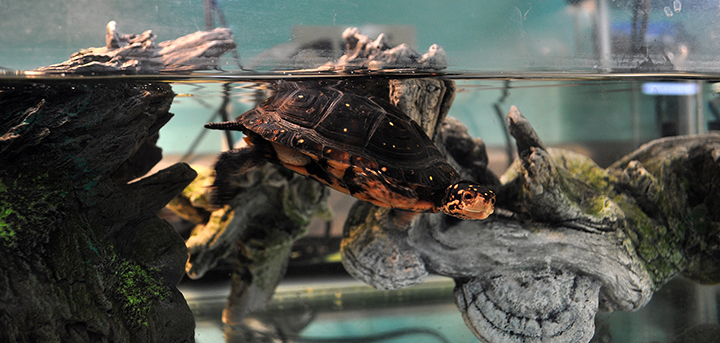

The drop off process for animals that are brought in is simple. The rescuer fills out an intake card which will stay with the animal throughout the rehabilitation process. Then the animal is allowed half an hour to calm down from the stress of rescue. After that an exam is conducted on the animal to determine injuries, illnesses and aliments that affect the animal. If the animal is able to recover it is released back to the wild; if the animal is unreleasable it is housed at the facility indefinitely. Turtles are an exception to the release rule as they must be returned within a one-mile radius due to their uncanny ability to locate their nests over large distances.

The Carolina Wildlife Center is hoping to expand its facility and an initial round of meetings have begun for the board of directors to look for a larger space for the facility. Donations and volunteers are always welcome to help the center and a wishlist is available for the public to view on its website.

The Carolina Wildlife Center maintains a breeding program for spotted turtles to help bring the species back from the brink of extinction.

Carolina Wildlife Center Executive Director Jay Coles holds an opossum that was blinded in one eye by another creature and cannot be released into the wild. Opossums are North America’s only native marsupial and possesses natural immunizes to the rabies virus and snake venom.

This Pekin duck was brought to the Carolina Wildlife Center with an injury that left it with half an upper bill. Pekin ducks are not native to South Carolina and have little defense against native predators.