Portions of the West Columbia Riverwalk were underwater after the Columbia area received more than three inches of rain on Thursday, Feb. 6.

By JOSEPH LEONARD and MAE BING

Imagine if South Carolina had a system that identified flooded areas, risks of flooding and assessed damage in real time during the devastating 2015 “thousand-year” flood.

Erfan Goharian and Song Wang, engineering professors at University of South Carolina, are hoping to do just that by building a flood prediction and early warning system for the Midlands using the latest artificial intelligence technology.

The two, who were awarded a grant from Microsoft to undertake the project, want the dataset completed and available to the public by the end of this year. The researchers are hoping to obtain additional monies to further the project.

The system would use artificial intelligence to analyze images of flooded areas and predict the damage they could cause. Once an image is recognized by the artificial intelligence, unmanned drones would be dispatched to further confirm the flooding. Also cameras located around Columbia would be used for capturing photos. These could be either existing cameras – such as street cameras or traffic cameras – or newly installed cameras to accompany the system, Goharian said.

“This is probably one of the most important problems we have in this state,” Goharian said.

In October 2015, Hurricane Joaquin ripped through South Carolina, killing 19 as the storm pelted the state with an average of 2 inches of rain per hour in many locations and caused nearly $1.5 billion in damages, according to the National Weather Service. At the same time, 51 dams either breached or failed, during the flooding, according to the state Department of Health and Environmental Control, setting in motion devastating flooding that swamped some Columbia neighborhoods and communities across the state and sent residents fleeing into the night.

Goharian said the idea for the system arose because of the lack of tools to pinpoint flooded areas and dispatch emergency personnel to respond.

“So, it can improve the time of response, it reduces the human error and human resources [needed],” Goharian said. “It decreases the delays… it provides visual information during the decision-making process.”

Crowdsourced photos collected from social media are also a source for the image dataset, which could be used to report to local and state governments.

“It’s always good information because the public could identify immediately what the critical areas are,” which would trigger drones, Roberto Ruiz, a South Carolina Department of Transportation hydro support engineer, said.

Although SCDOT is not involved in the creation of the dataset, Goharian and Wang both want the agency and other local and state governments to have access to the dataset.

Along with images, the dataset will have numerical measurements gauging the depth of the bodies of water such as lakes, ponds and rivers in the Midlands, Goharian said. If water levels rise or fall, the AI system registers a potential flooding event and alerts. The dataset will also be able to detect droughts and the change of water quality.

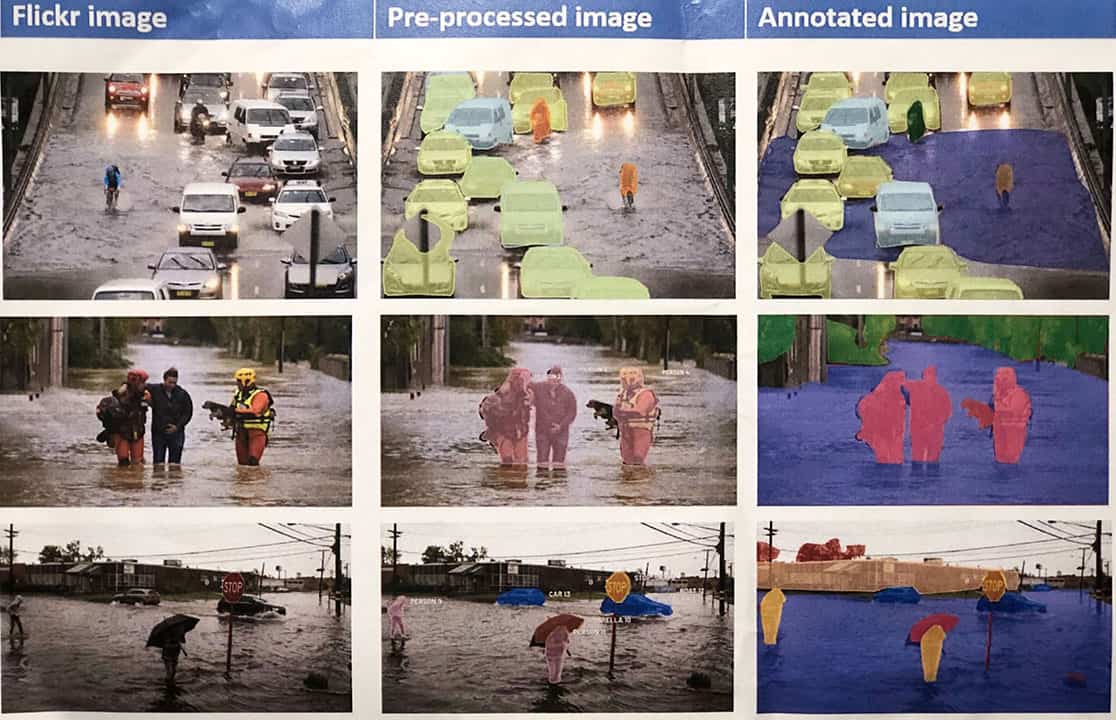

AI will recognize these changes and then report to local governments so it can prepare its response teams. Drones would then be dispatched to the areas for analysis, to take photographs of the areas and color coordinate objects that correspond to a programmed code. For example, humans might be coded as pink, water as blue and cars as yellow.

Goharian said water itself is an obstacle for creating the system because of water’s fluid movement and shape. However, using color-coordinated maps would allow the system to distinguish between people, cars, trees and the flooding water.

“It’s not just a water body detection,” Wang said. The system will have to distinguish between these natural bodies of water and unnatural flooded areas.

Tom Knight said SCDOT already uses its own drones and said more drones and data from the new AI system could help their response team. However, Knight, SCDOT’s director of policy and engineering, said one obstacle using drones is having the proper drone license.

Knight said initial flooding data is collected from SCDOT maintenance workers in the field, rain gauges and United State’s Geographical Survey’s national water data that is updated hourly. SCDOT also uses an application called Bridge Watch that reports radar rainfall, gauges flows and has a predetermined trigger that alerts when the water level threshold is exceeded.

“They’re limited. I wish there were more,” Ruiz said of SCDOT’s river measurement gauges. Ruiz also said the data could be used to help identify which road closures are needed.

Wang said his students will be testing the system in coming months and he hopes it could in place quickly. “We also can make this public for… public users,” Wang said. “It can be used very widely.”

Erfan Goharian, USC engineering professor, explains the differences in current flooding detection technology and his newly proposed artificial intelligence system.

Goharian created a photo detailing the color coded images that distinguishes humans, cars and water in the artificial intelligence system.

Song Wang, USC engineering professor, explains the limitations and difficulties with creating flooding data, because of the fluidity of water’s shape and size.

A pier and sidewalk on the West Columbia Riverwalk was underwater after rainfall of more than three inches was recorded in the Columbia on Feb. 6.