Former Republican congressman Bob Inglis (at right) now works to convince the GOP of climate change and free-enterprise solutions to address the problems. Photo courtesy of Price Atkinson and Northwestern University

Among the bright spots Inglis sees for the future of clean energy in South Carolina: the conversion of coal-fired energy plants to natural gas. McMeekin Station in Irmo completed its transition to natural gas in 2016.

Credit: De’Angelo Stevenson

South Carolina residents in opposition to offshore drilling gather on the State House steps on Feb. 14.

Credit: De’Angelo Stevenson

Before taking the chairmanship of the Palmetto Conservative Solar Coalition, Matt Moore served as chairman of the South Carolina Republican Party from 2013 to 2017.

Bob Inglis had an excellent reason for not buying climate change – Al Gore was selling it.

Now as he leads the Energy and Enterprise Initiative, a conservative group he founded promoting free-enterprise answers to climate change, Inglis finds the environmental views he held as a congressman in the 1990s “rather ignorant.”

“It was the end of the inquiry; Al Gore was for it, so I was against it,” Inglis said.

Inglis was elected in 1992 to represent South Carolina’s District 4, covering Greenville-Spartanburg, “the reddest district in the reddest state in the nation,” he said. From then until 1998, his environmental views were shaped in direct opposition to the Democratic vice president, whose “An Inconvenient Truth” book and film changed the way the world viewed global warming.

Inglis was re-elected to Congress in 2005. Not long after, Inglis’ son told his father to re-think his views on the environment, or else he might not get his vote.

That millennial admonition was the first step in the re-education of Bob Inglis. His second was a trip to Antarctica with the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology; the third was another committee journey snorkeling in the Great Barrier Reef.

There, Inglis made a connection with an Australian climate scientist which he deemed a “spiritual awakening.”

“I could tell that he and I shared a world view even though no words had been spoken,” Inglis said. “I could see that he was worshipping God in what he was showing me.”

On returning home, Inglis introduced the Raise Wages, Cut Carbon Act of 2009 to the House. The bill sought lower Social Security taxes to be offset by greater taxes on fossil fuels. It did not sit well with a Republican Party in the midst of the Tea Party wave of 2010.

“Note to self: Do not introduce carbon tax in midst of Great Recession in reddest district in reddest state in nation,” Inglis said with a laugh.

Inglis lost the District 4 primary in a landslide to Trey Gowdy, who suggested he and a majority of the 4th district constituents did not believe in climate change. (Gowdy recently announced his retirement from the House.)

As far back as 1998, the EPA found that sea level near Charleston was rising at a rate of 9 inches per 100 years, and predicted that the cost of sand replacement to protect the S.C. coastline from a 20-inch rise could reach nearly $10 billion. And given the impacts felt around the state by Hurricanes Joaquin, Matthew and Irma in consecutive years, those costs are only headed upwards.

Rouzy Vafaie, second vice chair of the Charleston County Republican Party, once discounted global warming. But after becoming friends with Inglis and listening to his initiatives, he came to accept both the scientific evidence and the Energy and Enterprise Initiative’s solutions.

“One argument I bring up with my climate change-denying friends is ‘Well, you know, if you guys are right and nothing changes, well, then great,’” Vafaie said. “‘We’re in perfect shape. But if you guys are wrong, by the time we can actually do anything about it, game’s over.’”

One of the main pillars of Inglis’ initiative is a carbon tax similar to the one he proposed in the 1990s, which he believes could sell well with conservatives if it lowers the necessity of some environmental regulations.

“Slightly smaller government means that once you put the carbon tax on, you can eliminate some Clean Air Act regulations,” Inglis said. “Not the entirety of the Clean Air Act, obviously, but some parts of Clean Air Act regulations can go away because by the pricing of carbon dioxide, it’s a proxy for those regulations.”

Inglis also supports a border adjustment tax, which he believes is necessary to keep trade competitive while still charging for carbon emissions.

“If we price carbon dioxide by ourselves and it didn’t have that border adjustment, then manufacturers would pick up and move from the United States to China,” Inglis said. “Once they got there, they’d emit more CO2 than they’re emitting here because China is less energy efficient than we are…if you can’t make this worldwide, it’s really fruitless to attempt it.”

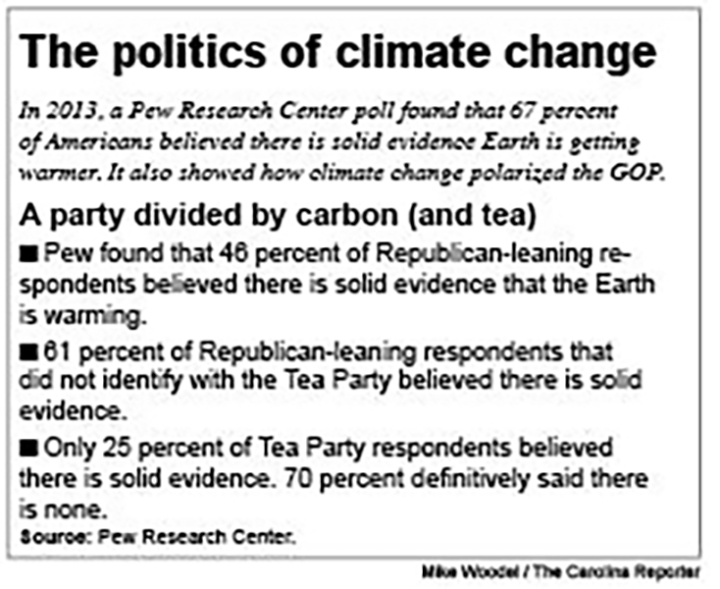

Of course, to get such policies in place, Inglis still needs a larger party-wide acceptance of climate change. Both he and Vafaie said there is growing agreement among Republicans of the human impact on the climate. But both also agree that some sectors of the party are harder to sway than others.

“When I speak in the Young Republican circles, I think it’s unanimously believed that there is [a human] impact,” Vafaie said. “As the age groups go up, I find it extremely difficult to convince people.”

Inglis said he believes conservatives are responsive to his solutions but that “populist nationalist” voters, especially those believing the narrative of a “war on coal,” are a different story.

“I think we got a good shot with conservatives,” Inglis said. “We got a hard, hard road to hoe with populist nationalists.”

Matt Moore chaired the South Carolina Republican Party from 2013 to last May. Now the chairman of the Palmetto Conservative Solar Coalition, Moore works to make it easier to establish a free market for solar energy in South Carolina. Like Vafaie, he sees growing acceptance of climate science within his party’s young people.

“For millennials, anyone with a brain can see that humans contribute to environmental emissions,” Moore, a graduate of Georgia Tech’s industrial engineering program, said.

Moore said solar energy is very much on the rise in South Carolina since the state adopted net energy metering in 2014. Under net metering, residents owning solar panels receive reimbursements on their electric bills for the energy their panels return to the grid. The deal also allows producers to avoid fees from state utility companies through the end of 2020.

“Conservation is conservative,” Moore said. “My job as chairman of the PCSC is to go out there and tell the story that Republicans can actually lead on conservation through innovation.

“Conservatives don’t want extreme government intervention, we in fact believe that market forces can drive innovation to create change,” Moore said. “And that’s what Congressman Inglis has been focused on now for a number of years. If we removed all subsidies on energy and created a true free market, then maybe these policies actually begin to make sense.”