Christina Andrews works in her office at the University of South Carolina.

Christina Andrews holds the Breakthrough Start award, which was presented to her for her research.

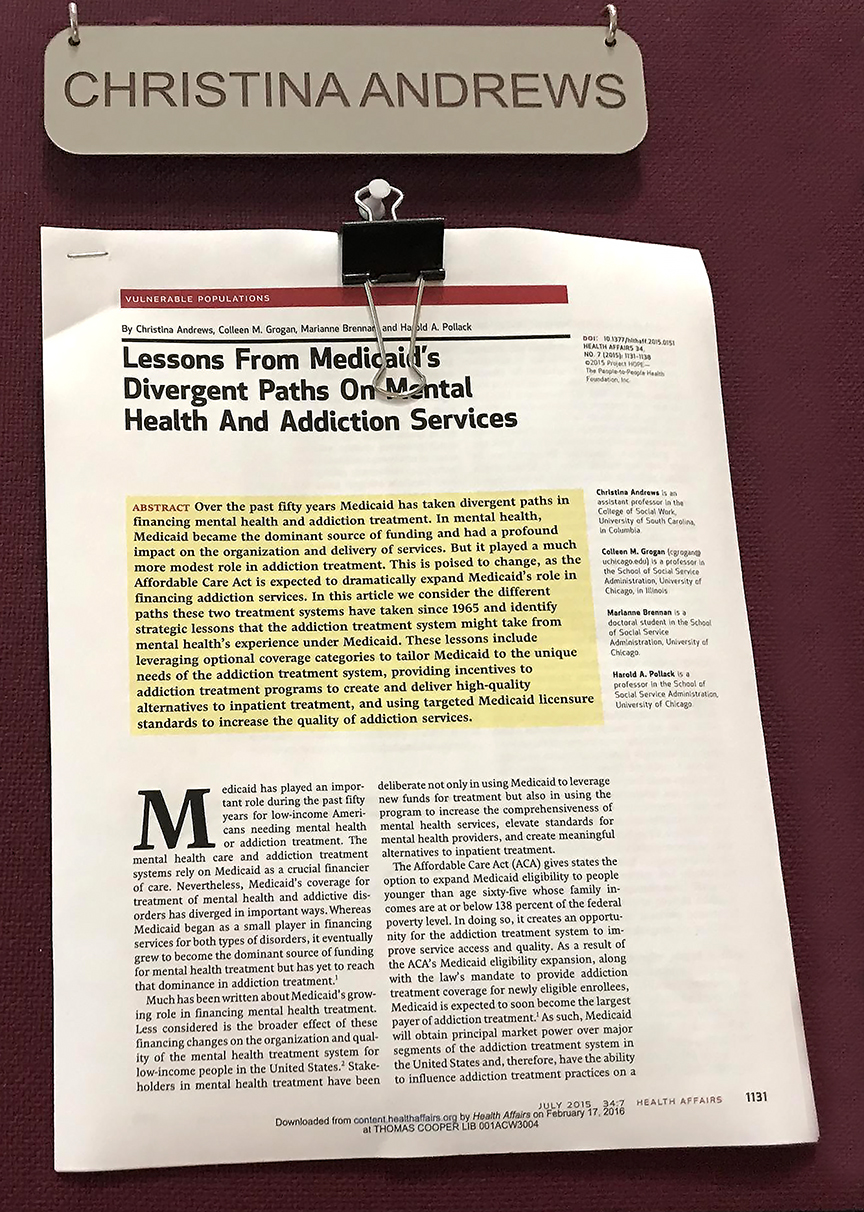

The USC College of Social Work displays some of Christina Andrews’ latest research.

Magnitude

Christina Andrews, a professor in the University of South Carolina’s College of Social Work, rolled her chair over towards her computer and pulled up a slide. Her office was completely clean. Everything appeared to be organized and in its place, which may be essential for someone who’s studying such a chaotic epidemic.

“I’ve got a slide that’s pretty cool where you can kind of see how things just happened,” Andrews said, sifting through a PowerPoint on her computer. “That was 1999, and it’s just been growing and growing and growing. [The Appalachia region] was the epicenter.”

Andrews is an expert on drug abuse, drug treatments, and the opioid crisis. She’s currently working on a national longitudinal study of drug treatment centers in the United States. She wants to find the best ways to combat the opioid epidemic because the magnitude of the crisis is far reaching. Andrews plans to apply her research to communities in South Carolina, to try and minimize the effects of drug abuse in our state.

“This is the most deadly drug epidemic in our nation’s history,” she said. “Deaths from opioid overdoses at this point have far-exceeded deaths from AIDS at the height of that epidemic.”

According to Avert, an organization that focuses on the global statistics of HIV and AIDS, at the height of the AIDS epidemic in America, around the beginning of the 1990s, there were over 100,000 reported cases in the United States. The World Health Organization predicted the actual number of cases were a couple hundred thousand more.

In 2015 alone, it was estimated that roughly two million Americans were struggling with abusing prescription drug pain relievers.

“It’s now become one of the top ten causes of deaths in the United States,” Andrews said.

Drug overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the U.S., with opioid-driven overdoses accounting for 60 percent of those deaths.

“We have seen for the first time in many years the decrease in life expectancy of Americans and that is almost wholly attributable to the epidemic,” she said. “It’s one of the biggest health emergencies we’ve ever had.”

In 2015 and 2016, reports from the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention indicated that life expectancy for Americans was declining. The U.S. has typically seen a gradual rise in life expectancy year after year, with only occasional years where the life expectancy stays the same or randomly declines.

The rates in 2015 and 2016 were the first time that the U.S. has seen a two-year decline in life expectancy rates since the height of the AIDS epidemic.

The life expectancy rates for a country typically reflect the well-being and level of health for a country.

“It could not be more serious,” Andrews said.

Prescriptions and South Carolinians

Andrews pointed to a location on a map that was covered in a dark red color.

“One place where they’re having a real problem is in Horry County, which is up where Myrtle Beach is,” she said. “There have been more [opioid-related] deaths there than any county in the state. Which is very concerning because it’s so much less populous than Richland County or Greenville County, where our cities are.”

South Carolina has not come out unscathed from the epidemic.

“Right now, in South Carolina, doctors write as many prescriptions for opioids as there are in the state, every year,” she said. “We’re in the top 10 in terms of the number of prescriptions per resident. Not a place you want to be.”

According to the CDC, the worst states for prescribing medications per residents were Alabama, Arkansas and Tennessee. South Carolina ranked ninth.

Andrews explained that it’s difficult to determine why the epidemic hits hardest in particular areas. Researchers are trying to figure it out, but there are a number of contributing factors as to why some areas are susceptible to the opioid epidemic.

One factor could be that rural areas, with many physically-demanding jobs, have higher rates of workplace injuries. Doctors were encouraged in the 1990s to prescribe opioid prescriptions for pain relief. As these injuries occurred, physicians were happy to prescribe medications like OxyContin, which were new on the market, to provide any kind of relief. The research just wasn’t there yet to prove how highly addictive these medications might be.

But it’s not just rural areas that have been affected, at this point.

“I think that because of the magnitude of the opioid epidemic there are very few people who aren’t touched by it one way or another,” Andrews said. “Either personally or by having a family member, or a friend, or a coworker, who’s struggling with opioid abuse.”

South Carolina is also seeing a growth of opioid addictions in the rural northwest counties.

“You’ve got this area around West Virginia that just keeps growing and growing, and now it’s starting to hit this corner [of South Carolina],” she said. “The concern is, what do we need to do as a state to keep it from spreading.”

A Federal Affair

Andrews has been studying drug abuse, and specifically the opioid crisis since she began her doctorate in 2006.

Her devotion towards studying the opioid epidemic, and particularly the positive effects of drug treatment and its financing, resulted in her being asked to serve as a witness for a U.S. congressional hearing.

“One of the major reasons I think I was asked to attend the hearing is because of the work [I do] around Medicaid and insurance expansions,” Andrews said. “Just that acknowledgement of how critical those funds are to states and communities really being able to leverage an effective response.”

The hearing was focused primarily on how necessary the funding of ACA and Medicaid is to the opioid epidemic.

“One in three people receiving treatment for opioid addiction is getting their treatment through Medicaid,” she said.

Andrews laughed about the timeline of getting to the congressional hearing, because everything happened very quickly.

“They asked me a week before. I had to book a flight, pull a testimony together and be there the next week,” Andrews said. “And I probably had 20 emails a day with their staffers, all hours of the day and night all weekend long.”

She emphasized how excellent everyone was to work with, and how beneficial it was that she had colleagues who had delivered congressional testimonies before.

“I was certainly a little nervous going into it, but I think what I realized pretty quickly was that you’re talking to a really generalist audience of lawmakers who have to understand a little about a lot of things,” she said. “And so, the questions that they were posing were excellent ones, but they were ones that I definitely felt equipped to speak to.”

Andrews said that funding for drug treatment and healthcare is crucial, and that is what got her to the hearing. Without money, people won’t receive necessary treatments for battling their addictions, and treatments have been proven to be the most effective way to cut down on overdose and addiction.

“The bottom line is that people will die,” Andrews said.

Why social work?

Andrews studied at the University of Chicago for her doctorate.

“The school’s motto was ‘Where fun goes to die’ and it was definitely challenging and serious,” Andrews said. “But, I felt like I had a team by my side through that whole program. I never had a moment of doubt that this is what I wanted to do with my life.”

Andrews felt drawn to social work because she likes to break down the big picture of an issue and find solutions for it. Social work gave her the freedom to study significant problems with real world applications, and brainstorm innovative methods for solving them.

Being the first of her family to go to college, Andrews didn’t expect opportunities that would become available to her.

“I think I thought I wanted to be a hairdresser,” Andrews laughed. “My family was working class. I’ve definitely exceeded my greatest kinds of expectations for things I thought I would do, which is wonderful.”

Andrews credits some of her work ethic to her mom. She joked about the yin and yang nature of their relationship, but recognized that her mom’s quiet and gentle support gave her the freedom to become who she wanted to be.

“She was a single mom raising my brother and sister and I on her own,” Andrews said. “I definitely got to see what hard work and personal sacrifice looked like.”

Hard work and personal sacrifice are two things that Andrews is familiar with. For years she’s devoted time to teaching and researching the effects of drug treatments for those struggling with opioid conditions. She’s always loved her job, even when she was working hours on end.

“It was time to go home and I just didn’t want to stop,” Andrews said. “I just love the work.”

Next Steps

“It sounds cheesy, but a real goal for me is to give back more to the community here,” said Andrews. “I’m interested in developing a coalition of key stakeholders to take on the issue of treatment here in South Carolina.”

She wants to convene the coalition as soon as possible, to determine where the gaps are in treatment, what the needs of South Carolinians are, and what resources South Carolina could still benefit from.

Andrews is hopeful for South Carolina and the future of medical treatment for individuals struggling with drug abuse.

“I think we need to focus on prevention and treatment,” Andrews said. “One out of every five people struggling with opioid usage is receiving any kind of treatment. On the prevention side, I think we need to focus on safer prescribing methods.”