Jason Johnson started doing drugs when he was 13, and spent over 20 years battling an opioid addiction before finally overcoming it.

Allison Bremfield, with the Lexington-Richland Alcohol and Drug Abuse Council, works to offer treatment options to victims of addiction in the Lexington and Richland areas.

By Delaney McPherson

CAROLINA REPORTER & NEWS

Jason Johnson was 13 years old when he started dabbling in illegal drugs, progressing from marijuana to LSD. What at the time seemed like harmless teenage fun spiraled into a heroin addiction that gripped Johnson for more than 20 years.

Johnson estimates he entered 25 to 30 in-patient programs all over the country, but he was never able to overcome his craving for drugs. He was caught in a cycle of addiction that he could not beat.

“I really just kind of lived on the fringes of society. There would be times where I would plug in, get a job, hold it together for a while, but inevitably it would fall apart,” Johnson, of Irmo, said.

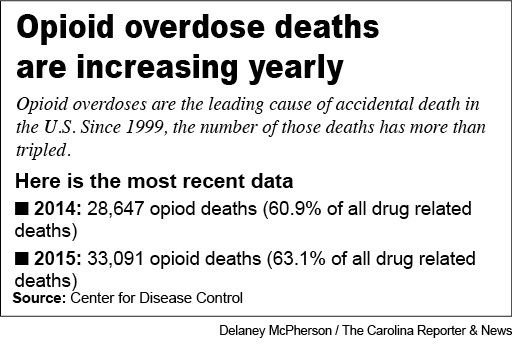

President Trump recently declared a national health emergency due to the opioid addiction epidemic in the United States. According to the CDC, opioid overdose is the leading cause of accidental death in the United States with over 30,000 a year.

The likelihood of an addict pulling themselves out of their addiction and recovering seems low, but people like Johnson prove that there is hope.

Like many addicts, Johnson said his family life suffered. He was divorced and estranged from his parents, brothers and children. At his worst, Johnson said he lived “like an animal.” Johnson recalls being in the throes of his addiction and feeling envious of how other people could live a “normal” life.

“I don’t need to be a millionaire; I don’t need some fancy home and a fancy car, and all this stuff. I just want to be normal and enjoy simply things,” Johnson said. “I don’t know, take my kids to get ice cream, have a hobby, have a place to stay for more than three to six months, be able to hold down a job and attend family functions. I just want to be normal, and I couldn’t.”

In order to properly address the issue of opioid addiction, experts say you have to look at what causes it, and why it is increasingly becoming a bigger problem.

Allison Brumfield, the community relations director at the Lexington Richland Alcohol and Drug Abuse Council, believes that the problem is rooted in the selling strategies of pharmaceutical companies in the 1990s. According to Brumfield, these companies would use false marketing practices to sell painkillers, claiming that they weren’t addictive or there was a very low risk of addiction, so that doctors would prescribe the drugs more.

“So with that we saw a big increase in people having it available and then from there we’ve seen more and more people become dependent on it and then, oftentimes, use it illegally and then unfortunately use heroin or something bigger than that,” Brumfield said.

Oftentimes, this is how heroin addiction starts. Brumfield says that people will start doing opiates legally, after being prescribed them following a surgery, or for chronic pain. Once the person is addicted, they will resort to illegal means to get the drugs, such as stealing pills from their parents’ or friends’ medicine cabinets. When a person cannot acquire those prescription drugs anymore, they will turn to heroin.

LRADAC provides both treatment for substance addiction and preventative programs. For many people, like Johnson, addiction starts in the teenage years. LRADAC has coalitions with local high schools to educate teens and their parents on the dangers of drug addiction and how to prevent it. Brumfield recommends parents having honest conversations with their kids about opiate addiction, locking medicine cabinets and counting pills to make sure none are being stolen. LRADAC also works with the DEA to arrange prescription pill drop offs for extra drugs that are not in use.

“So often I think it’s that an older adult has lost a parent, and they had so many medications including pain medications and they passed away and they just don’t know what to do with them because it’s hard to dispose of them safely,” Brumfield said.

Johnson began using opiates at age 15 by stealing them from medicine cabinets of people he knew. When he was no longer able to do that, he turned to heroin.

It wasn’t until two years ago that Johnson was finally able to overcome his addiction. He’s not sure what the catalyst for his recovery was, exactly, but describes it as the stars lining up in his favor.

“It was my second ambulance ride that week, and I wound up back in the emergency room, and they had me committed to a treatment center,” Johnson, 39, said. “I remember walking down the hill to the treatment center and thinking, best case scenario I’ll be doing this when I’m 50 years old, more likely scenario I’ll be in prison or dead.”

From that day forward, Johnson devoted himself to his recovery and has been sober ever since.

Brumfield laments that while there are many statistics about people dying from opioid addiction, it is difficult to find any about people recovering.

“There are millions of people that live in recovery from a substance use disorder and then of that group how many are recovering from an opioid use disorder, I don’t know. But they’re out there, and, really, there is hope,” Brumfield said. “I mean people who really struggle with this don’t have to stay that way.”

Today, Johnson enjoys the “normal” life that evaded him for so many years. He has rebuilt relationships with his family and children, holds a steady job at a salon, attends school and took up bike riding as a hobby. Like Brumfield, he sees the lack of statistics on opioid recovery, but he doesn’t think people should be disheartened by it.

“It can happen, it can get better, and your life can become really rich and fulfilling and meaningful,” Johnson said. “And you can find purpose. And things change, things can substantially change for the better.”