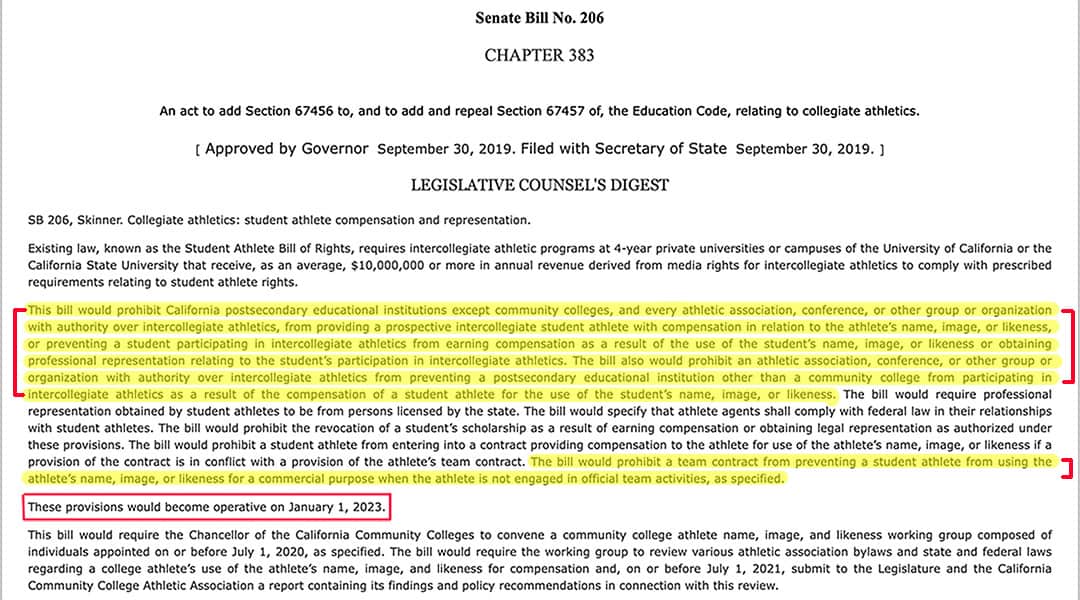

The Fair Pay To Play Act that passed in California on Sept. 30 was signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

South Carolina lawmaker Marlon Kimpson said Tuesday California’s new law that would pay collegiate athletes could be a building block for South Carolina and other states to pass similar legislation to pay collegiate athletes. But he isn’t hopeful.

“Frankly, I’ll be honest with you. We are facing an uphill battle,” Kimpson, a Charleston Democrat, said. Representatives of two of the state’s most prominent football programs haven’t endorsed the bill.

The law passed in California will allow collegiate athletes the opportunity to profit off their names and likenesses for the first time in NCAA history. The bill will not force schools, conferences or the NCAA to pay athletes; instead it will allow athletes to hire agents who can secure sponsorships deals. The California law will go into effect January 1, 2023. Current NCAA bylaws prohibit players from receiving incentives or endorsements while participating in NCAA athletics.

California’s Act is about empowering college athletes to negotiate their own contracts with third parties over the use of their names, images and likeness. The legislation will allow college athletes to negotiate deals to be in video games, advertisements, attend autograph signings, appear in TV commercials and sign endorsement deals with companies. It is unlikely that a majority of collegiate athletes in California will be able to secure an endorsement deal in less popular sports such as tennis, softball, soccer and equestrian.

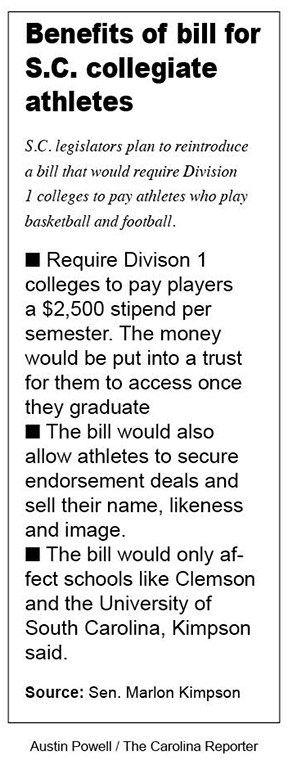

Kimpson and Rep. Justin Bamberg, D-Bamberg, proposed a bill in 2014 and 2018 similar to California’s except the bill would affect only the state’s biggest Division 1 colleges. It would not include small colleges like Benedict and Winthrop University, he said. He plans to reintroduce the legislation in January when the legislature meets again.

On Tuesday, he got a boost from Harvey Peeler.

“Having a sports team and not allowing the players to make money is like being in the Dairy business and not allowing the cows access to the feed trough,” Peeler said on Twitter.

The proposal would require the state’s biggest colleges to pay a $5,000-a-year stipend to athletes in profitable sports like football and men’s and women’s basketball as long as the student is in good academic standing. The money would go into a trust and be awarded to the athlete in a lump sum upon graduation.

“The stipend is associated with the number of hours players spend participating in sports with the school. These players spend about 40 hours a week practicing and studying equivalent to the American work week and I believe they should be compensated for their labor.”

Kimspon said former USC running back Marcus Lattimore’s injury inspired him to push for a change. Lattimore’s career at South Carolina was cut short following a leg injury in 2013. He had a short stint in the NFL before retiring in 2014.

“In law school I witnessed the career ending injury to Marcus Lattimore and I decided more must be done,” Kimpson said. “Many athletes give so much to the school and don’t go onto the NFL.”

Like California’s bill, the S.C. proposal would allow players to sell their name, likeness, and image. However, unlike California’s bill the S.C. proposal would require colleges to pay student athletes that participate in revenue generating sports like football and basketball.

In response to the Fair Pay To Play Act proposal, the NCAA Board of Governors sent a letter to California Gov. Gavin Newsom disagreeing with his decision to pass the bill and calling it “unconstitutional.”

“Right now, nearly half a million student-athletes in all 50 states compete under the same rules. This bill would remove that essential element of fairness and equal treatment that forms the bedrock of college sports,” members of the NCAA Board of Governors said in the letter.

After the bill passed on Sept. 30, the NCAA said in a statement, “As a membership organization, the NCAA agrees changes are needed to continue to support student-athletes, but improvement needs to happen on a national level through the NCAA’s rules-making process.”

At SEC football media days 2019 USC athletics director, Ray Tanner opened up about his opinion about the compensation of NCAA athletes.

“This is personal opinion but when I see name, image, likeness it makes me feel like it is pay for play,” said Tanner.

Tanner received a contract extension in April that is set to pay him $1 million per year through June 2024.

Clemson head football coach Dabo Swinney hasn’t been shy about his views on paying college athletes.

“They may do away with college football in three years. There may be no college football. They may want to professionalize college athletics. Well, then maybe I’ll go to the pros. If I’m going to coach pro football, I might as well do that,” Swinney said in an interview with ESPN.com.

Swinney signed a new 10-year, $93 million deal in April that pays him an average of $9.3 million per-year. The deal made Swinney the highest paid coach in college football history.

USC football head coach Will Muschamp signed a contract extension in 2018 that pays him an average of $4.7 million a year through 2023.

California Gov. Newsom said there was one goal in mind when he signed his name on the bill.

“It’s fairness. At the end of the day it’s about rebalancing the power structure now that is dominantly in the hands of a few people in the institutions and the NCAA,” Newsom said on the Dan Patrick Show Tuesday.

Kimpson said another reason for his concern over athletes’ pay was the use of NCAA athletes’ likenesses in video games.

From 1993 until 2013 Electronic Arts (EA) created the NCAA Football video game series that featured players and colleges around the country. The game featured a selection of Division One FBS and FCS teams’ rosters but didn’t include players’ names in the game.

EA halted production of all NCAA video games after former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon sued the NCAA, EA and Collegiate Licensing Co. over the use of former players’ images. Judge Claudia Wilken ruled that the NCAA’s long-held practice of barring payments to athletes violated anti-trust laws. The players featured in the games didn’t grant EA or the NCAA permission to use their images or likeness. The NCAA, EA, and broadcasting companies profited off the game while the players didn’t receive compensation.

Charleston Sen. Marlon Kimpson and Bamberg Rep. Justin Bamberg are planning to reintroduce a bill in January that would require colleges to pay student athletes.

Charleston Sen. Marlon Kimpson said he was inspired to push for paying collegiate athletes after witnessing Marcus Lattimore’s knee injury during his USC football career. Credit: Marlon Kimpson

If Kimpson’s proposal passes, the University of South Carolina, along with other Division 1 team, would have to alter the way it handles student athletes.

The bill in South Carolina if passed, would only affect Division 1 schools like Clemson and UofSC, Kimpson said. Credit: South Carolina Athletics.