Japanese honeysuckle in bloom. The pink stem indicates a hybrid developing. (Photo courtesy of Linda Lee from USC Herbarium)

The Japanese honeysuckle has been used in people’s yards as a natural fragrance, but invasive plant coalitions warn the non-native plant is a big threat to the state’s ecosystem.

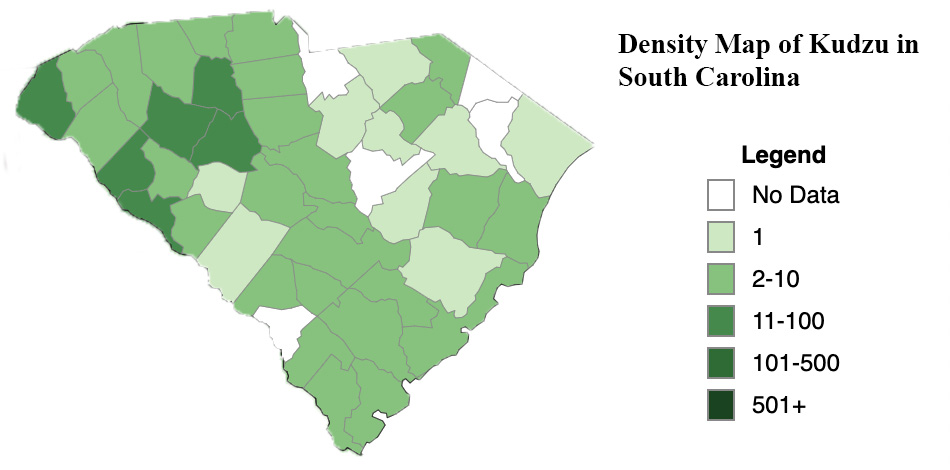

Japanese honeysuckles can come in the form of shrubs or vines. The vines — like kudzu, the Southeast’s most-invasive mortal enemy — are capable of growing up and over trees. That blocks the native plant’s access to sunlight, and the plant dies, according to Lillian Self, a research assistant at the University of South Carolina.

“The vines and bushes can get really big,” Self said. “The vines can grow on top of the tree canopy and shade out the native trees, causing them to not get as much sun. Now think about what would happen if honeysuckle took over a whole forest.”

The Japanese honeysuckle is native to Eastern Asian countries such as Japan and Korea. The plant was brought to the United States in the 1800s to be used for decoration and erosion control. It’s the vine, not the bush, that everyone is worried about. It even seems a little sci-fi.

Japanese honeysuckles are fast growers and can adapt quickly to a new environment. Some people may unintentionally be spreading them.

“Invasive plants have pretty incredible ways of overtaking environments,” said Jordan Franklin, a consumer horticulture agent with the Clemson Home and Garden Information Center. “People may unintentionally spread the plant by picking the flowers and then dropping them in other places. People could even brush up against the plant and it can spread from your clothes.”

The vine has been around long enough for some plant guidebooks to list it as a local species, according to Herrick Brown, a USC biology professor who is also a curator for the A.C. Moore Herbarium.

“As a kid, I have always enjoyed picking the green bulb inside the flower,” Brown said. “When you smash it with your fingers, you get sort of a honey scent. I think many people have fond memories doing this as kids and don’t realize how invasive the plant is.”

The South Carolina Exotic Pest Plant Council is a local coalition of state, federal, and non-profit groups. The council lists all the invasive plants in the state and ranks them by severity of their invasiveness. The Japanese honeysuckle is listed as a “severe threat” due to how quickly the plant can grow and its adaptability.

“In urban environments like Columbia, you may see this species sort of take over areas in high-light situations,” Brown said. “Birds will eat the berries and carry them in their bellies before releasing them in more rural habitats, but usually when you encounter Japanese honeysuckle in an otherwise ‘pristine’ habitat it probably means there was human activity not far away even if that activity occurred decades ago.”

Experts recommend people take time to clear their backyards of the plant before it is able to spread. The best way to dispose of Japanese honeysuckle is to use environmentally safe herbicide on the root of the plant. It’s important to dispose of the debris because the leftover vines and fruits are capable of regrowing if left on your lawn.

“The main thing is to eliminate it in your yard or whatever property you may be responsible for,” Franklin said. “It can be a big job, depending on the size of the growth. If you can, remove it and prevent it from growing.”

This is a standard Japanese honeysuckle in bloom. (Photo courtesy of Linda Lee from USC Herbarium)

This is a Japanese honeysuckle fruiting. These are the types of fruits that birds eat and inevitably replant elsewhere. (Photo courtesy of Linda Lee from USC Herbarium)

This is a density map of kudzu sightings in South Carolina. The map is used to compare the density levels of kudzu and Japanese honeysuckle. (Connor Bird/ EDDMapS database)

This is a density map of Japanese honeysuckle sightings in South Carolina. The map is used to compare the density levels of kudzu and Japanese honeysuckle. (Connor Bird/EDDMapS database)