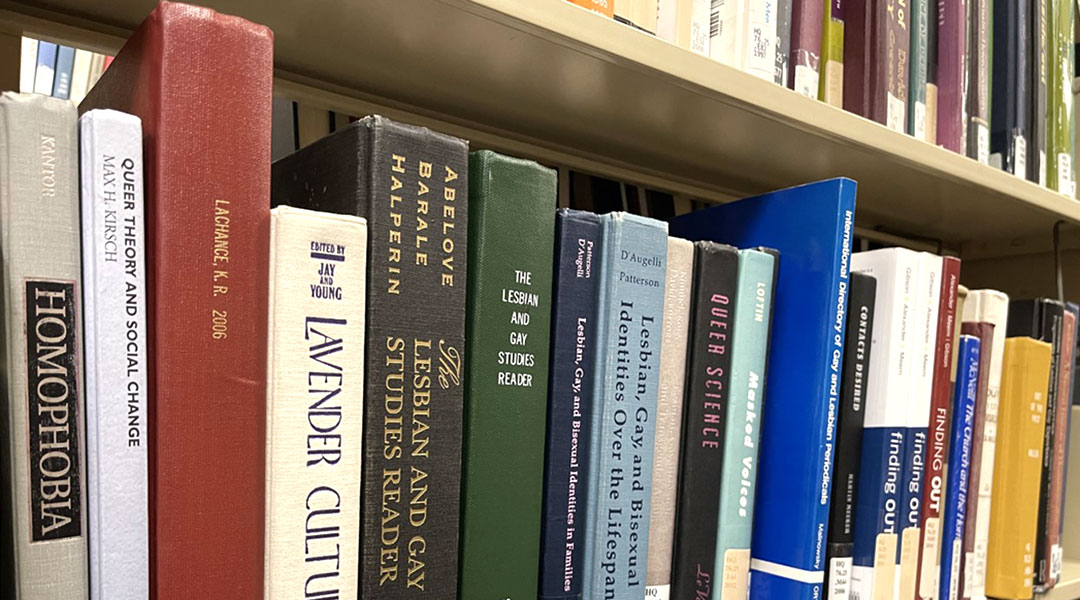

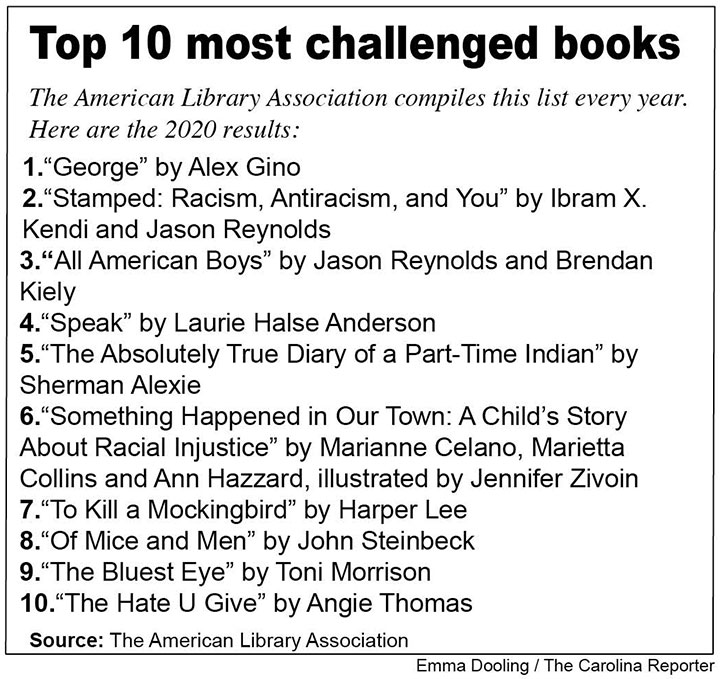

Materials and services with topics related to the LGBTQ community were some of the most challenged in 2020, according to the American Library Association’s State of America’s Libraries Report 2021. Photos by Emma Dooling

The empty room that would soon be Westwood High School’s library echoed back at Kathy Carroll. Before the opening of the Richland 2 school in 2012, she and a co-worker embraced their profession’s guiding principle: filling bare shelves with books that would challenge, enlighten and enliven students’ lives.

“We felt the need to create this space, this hub, this central part of the school. And to have to select the books and the resources and everything, it was a lot, but it was one of the most fulfilling professional experiences of my career,” said Carroll, now the media specialist at the Blythewood, South Carolina school.

Book selection is a librarian’s central responsibility. Now, Carroll and her fellow librarians are working to defend their decisions in the wake of increased and politicized book challenges and attempts to remove or restrict materials from a library or classroom.

Jenna Spiering, an assistant professor in UofSC’s School of Information Science, said there has been an “uptick” in book challenges in recent years.

Carroll, who is a council member for the American Library Association (ALA) and a board member for the American Association of School Librarians, said she has not received any book complaints during her time at Westwood. But fellow librarians in other states have not been as fortunate, some even having been “verbally accosted” by parents.

“This is an interesting time to be a librarian,” Carroll said. “This is a moment in time that’s going to be very decisive about the direction of a lot of things in education.”

National examples of challenges include a Kansas school district that removed 29 books from its libraries and a Texas GOP lawmaker’s attempt to have 850 books banned in state schools. The debate erupted in South Carolina specifically after Gov. Henry McMaster wrote a letter to the S.C. Department of Education and State Superintendent Molly Spearman on Nov. 10. In the letter, McMaster called for an investigation into books with “obscene and pornographic depictions” in public schools.

McMaster’s letter was a reaction to a parent petition for the Fort Mill School District to remove the book “Gender Queer: A Memoir” by nonbinary author Maia Kobabe from schools.

On Monday, the ALA condemned recent attempts to censor and remove books with topics on race, gender and sexuality from school libraries.

“We are committed to defending the constitutional rights of all individuals of all ages to use the resources and services of libraries,” the ALA said in a statement. “We stand opposed to censorship and any effort to coerce belief, suppress opinion, or punish those whose expression does not conform to what is deemed orthodox in history, politics, or belief.”

For Spiering, the debate over controversial books in schools is simple.

“The bottom line is that it’s the library’s job to make books accessible for everybody, and then it’s everybody’s right to decide what they want to read,” Spiering said.

Spiering’s research has found that there is a need for school library books to represent all students.

“Everybody deserves to see their reality, and they also deserve the opportunity to learn about people that are not like them,” Spiering said.

Carroll said a library’s lack of variety in perspectives would not make it a welcoming place for all students.

“If we were to remove every book that had reference to that population, what message are we sending those students?” Carroll said.

Sarah Seegars, the director of library experience for the Richland Library, said that while librarians must make a collection representative of its community, parents have a right to monitor the books their children receive from libraries.

“That is a parent’s choice to guide their own child’s reading, and we have librarians all over, and that’s our favorite thing to do is pick out books for people,” Seegars said.

To select and purchase books for school libraries, Spiering said a librarian typically looks through professional journals that review new books for school libraries. These reviews include information such as summaries, assessments of literary value and age group recommendations.

Librarians also look for books that have garnered awards or recognition. Organizations, such as the South Carolina Association for School Librarians, make annual lists of nominees for its children and young adult book awards.

“It is not something that is done haphazardly. It is very intentional,” Carroll said.

Reconsideration policies for books that are challenged are more formal than selection processes, according to Spiering. They involve not only the school librarian, but also parents and school and community leaders.

On Nov. 9, the S.C. Department of Education invited the public to review proposed instructional materials for public schools. The review will be open to the public until Dec. 9, and the materials and any public comments made on them will be submitted to the State Board of Education for final consideration on Dec. 14.

Spiering said she hopes that the review processes for both instructional and library books are fair and that multiple people read a book before any decisions on its appropriateness are made.

“Sometimes it’s really easy to just pull out one part of a book, one scene, and say, ‘Ugh, this is inappropriate,’ but sometimes if you read it in the context of the book — the whole meaning behind it — then you have a different read of it,” Spiering said.

Spiering and Carroll both emphasized the extensive education and training librarians are required to have. This experience, Carroll said, allows librarians to put students and community members at the forefront of their decision-making.

“What I hope we can all agree on is that all of us, regardless of what side of this we’re on, we want what’s best for our students, for our children,” Carroll said.

Kathy Carroll, a media specialist at Westwood High School in Blythewood, South Carolina, said she has been fortunate to have productive conversations with parents, school leaders and other librarians in South Carolina about the importance of diversity in library collections. Photo courtesy of Kathy Carroll

Jenna Spiering teaches students in the School of Information Science about the history of banned and challenged books in a Children’s Literature course in the spring of 2019. Currently, she teaches Young Adult Materials and School Library Program Development while supervising the school library internship course. Photo courtesy of UofSC

Richland Library director of library experience Sarah Seegars said the 13-location library system tries to represent a “broad spectrum of knowledge and diverse opinions” in its collection so that everyone feels “valued, welcomed and represented.”