Destiny Gettis was a 19-year-old sophomore at the University of South Carolina when she found out she was pregant with her now one-year-old, Sophie.

The teenage birth rate is on the decline in South Carolina, a state that teaches abstinence in schools as the best and first option for student contraception. But this decline seems to be due to various unconventional channels of sexual education rather than to the state’s sexual education curricula.

“I was educated in South Carolina public schools and when I was in eighth grade we had sexual education,” Destiny Gettis, a young single mother and 21-year-old senior journalism student at the University of South Carolina, said. “We talked heavily about abstinence. We did learn some about how condoms work and about birth control, but it was only to do with marriage and family planning in the future.”

Gettis was 19 when she found out she was pregnant. She gave birth to her daughter, Sophie Gettis, five days before her junior year of college began. Now, her day-to-day routine includes not only senior year college courses and an internship that she commutes to in Charlotte, N.C., but also supporting and spending time with her one-year-old daughter.

“Sophie is the best thing that ever happened to me,” Gettis said. “I did call Planned Parenthood when I found out I was pregnant and they could barely understand me because I was just sobbing.

“I was worried that if I had my child I wouldn’t be able to do what I wanted to do with my life and still provide for her,” she said. Being a single mom and being in school, sometimes people joke about it or you feel ashamed or wonder how you will do it. It is mentally, emotionally and financially a lot, but it is very much possible.”

In 2017, there were 3,406 teen mothers statewide who found themselves in a similar position to Gettis. South Carolina now ranks 16th out of 50 states plus Washington D.C. for teen birth rates, a 70 percent drop since 1991, when teen births reached their peak in the state.

From 2016 to 2017 alone, there was a nine percent decrease in teen births statewide. Experts note that the decline isn’t due to an increase in the abortion rate. In 1991, 14,112 abortions were performed on state residents; in 2018, that figure fell to 10,716.

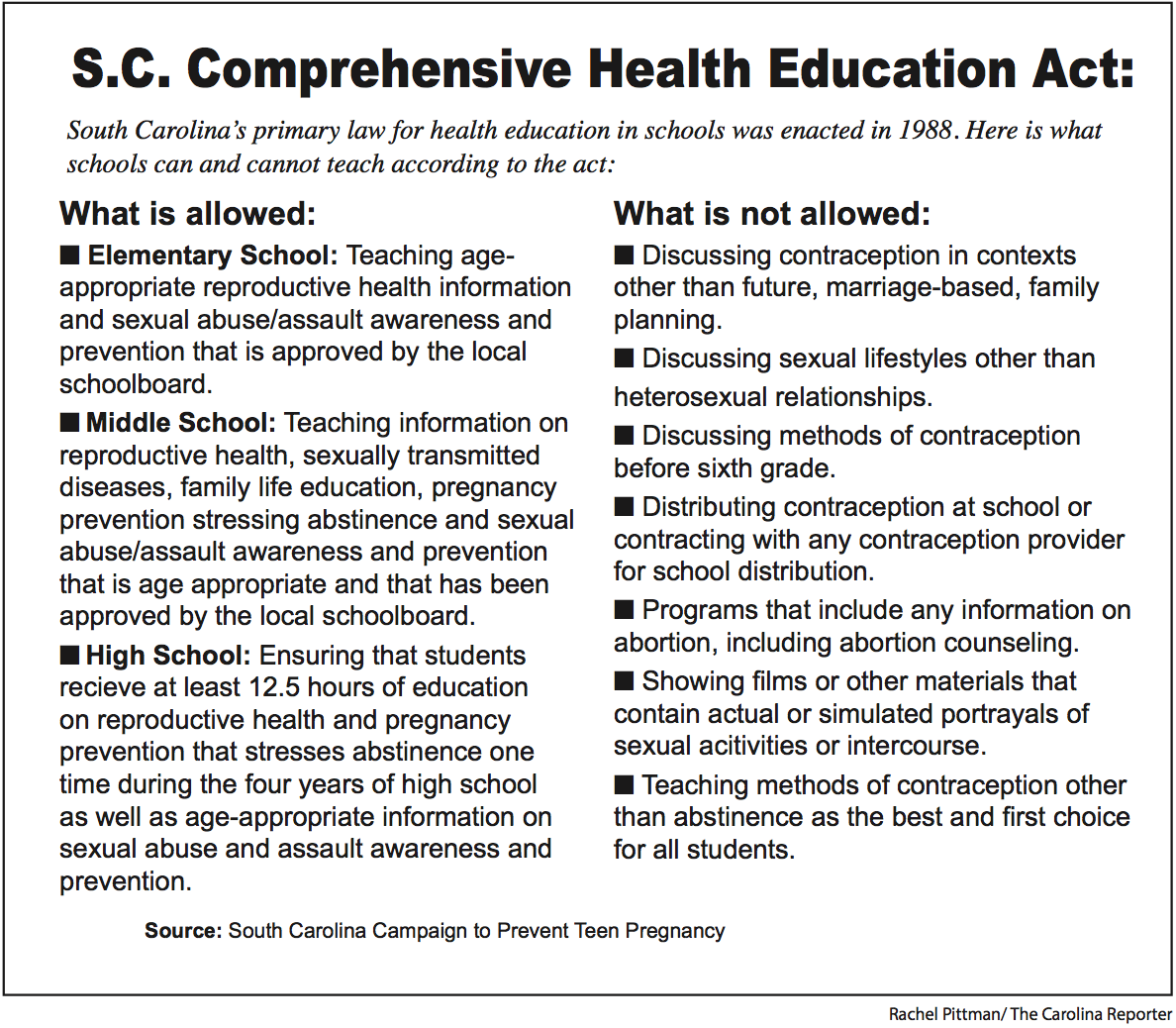

The Comprehensive Health Education Act (CHEA) is South Carolina’s primary law for establishing guidelines for public school sexual education. It was enacted in 1988 and has remained unchanged since that year. According to this law, individual school boards must submit their sexual education programs to be approved by the state.

In order for a program to be approved, it must teach abstinence as the best contraception method, teach other contraception methods only in the context of future, marriage-based family-planning, avoid teaching on any sexual practices that occur outside of marriage or that are unrelated to reproduction and avoid discussion on sexual behaviors other than heterosexuality in classrooms.

“DHEC receives federal and state funding for an Abstinence Education Program as well as a Personal Responsibility Education Program,” DHEC Public Information Officer Laura Renwick said in an email. “The Abstinence Education Program provides information and resources about abstinence and positive youth development while the Personal Responsibility Education Program provides information and resources about abstinence, contraception and healthy relationships.”

These programs are taught nearly identically in 2018 public schools as they were in schools when the teen birth rate peaked in 1991, prompting the question of whether or not other factors than public school sexual education are involved in the teen birth rate decline.

Some suggest the safety of long term birth control methods such as Nexplanon and IUD’s for adolescent girls as well as the easy access that teens have to sexual information through the Internet has given teenagers more information on ways to avoid getting pregnant.

“What accounts for this decrease? I think it’s a myriad of things,” Doug Taylor, the director of community programs for the South Carolina Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, said. “People just have more access to information now. There’s a delay in sexual activity in young teens and teens that do decide to be sexually active are doing a better job of getting on a birth control method. More teens are using contraception methods that are more effective and longer lasting.”

The South Carolina Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy is an organization that collects data on teen pregnancy in South Carolina yearly. The group provides resources for school sexual education programs as well as programs in community centers and other locations. Its educational information deals mainly with teen pregnancy, but also extends into other areas including sexually transmitted infections (STI’s) and LGBTQ health resources.

The campaign recognizes some areas of education that are not provided for in the CHEA, and teaches abstinence as an effective contraception method, but only until a person decides to become sexually active rather than until marriage. However, there is only so much additional information the campaign can provide to teens while staying within the guidelines of the CHEA.

Organizations like Planned Parenthood operate outside of the CHEA, allowing them to offer education on contraception and also on abortion. Their organization does teach abstinence, but as one of many methods of contraception rather than as the single most effective form.

“Abstinence and skill building around saying no to sex are important parts of any good sex education program, but they’re not the only parts,” Christi Hutchinson, community educator for Planned Parenthood South Atlantic in Columbia, said. “Almost no abstinence-only until marriage program has been shown to have any impact on young people’s behavior. Even more importantly, withholding critical, possibly life-saving information about STIs and HIV puts young people’s health and future at risk.”

While Planned Parenthood and the S.C. Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy see room for improvement in the CHEA, opening up the act for revisions could clear a path for more restrictive sexual education. With changes to the act unlikely, teens are left with the often-inadequate CHEA-approved information provided by their schools. Many of these teens are often unaware of educational resources like Planned Parenthood and the campaign as well.

In addition to schools and community organizations, students learn about sex from the Internet, their peers and, most importantly, their parents. Americans have a complicated relationship with sexuality, especially in the South, where religion often interferes with sexual education. Many parents are reticent to discuss sexuality with their children, but the role that parents play in their children’s sexual education is a critical one.

“Because of our religious traditions and backgrounds, American culture has a bit of a schizophrenic relationship with sexuality,” Taylor said. “We all, including children, are immersed in sexuality in our media culture and yet we can’t talk about it in an effective way. Parents who have quality conversations with their children as they’re growing up on love, sex and relationships have children who will delay initiation of sex. Then when they do engage in sexual activity, they’re more than likely to use contraception.”

As a young parent, Gettis is already thinking about how she will educate her daughter when the time comes. She knows that some of her child’s sexual education will come from her school, and hopes for future improvements to the state’s sexual education curricula. She plans on supplementing whatever she learns in the classroom by presenting all methods of contraception to her.

“I want Sophie to learn about abstinence but I don’t want her to see that as her only option,” Gettis said. “Teenagers are so curious and I think only teaching abstinence isn’t really doing anything for them. It only makes teens more curious to learn about what happens when they don’t practice abstinence. I’m going to teach my child all measures of contraception, way more than solely practicing abstinence like what is taught in most of South Carolina.”

Doug Taylor, director of community programs and evaluation at the S.C. Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy, is part of a group that works to lower the teen pregnancy rate in the state by informing students of various forms of birth control.

Destiny Gettis said that she hopes in the future her daughter Sophie, above, will have better sexual education in school, learning how to best avoid a teenage or unplanned pregnancy.

The S.C. Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy informs teens about topics other than contraception like sexually transmitted infections, vaccines, personal trauma and LGBTQ lifestyles.

Destiny Gettis, 21, hires a babysitter to keep her daughter Sophie during the day while she attends class, completes an internship and works.