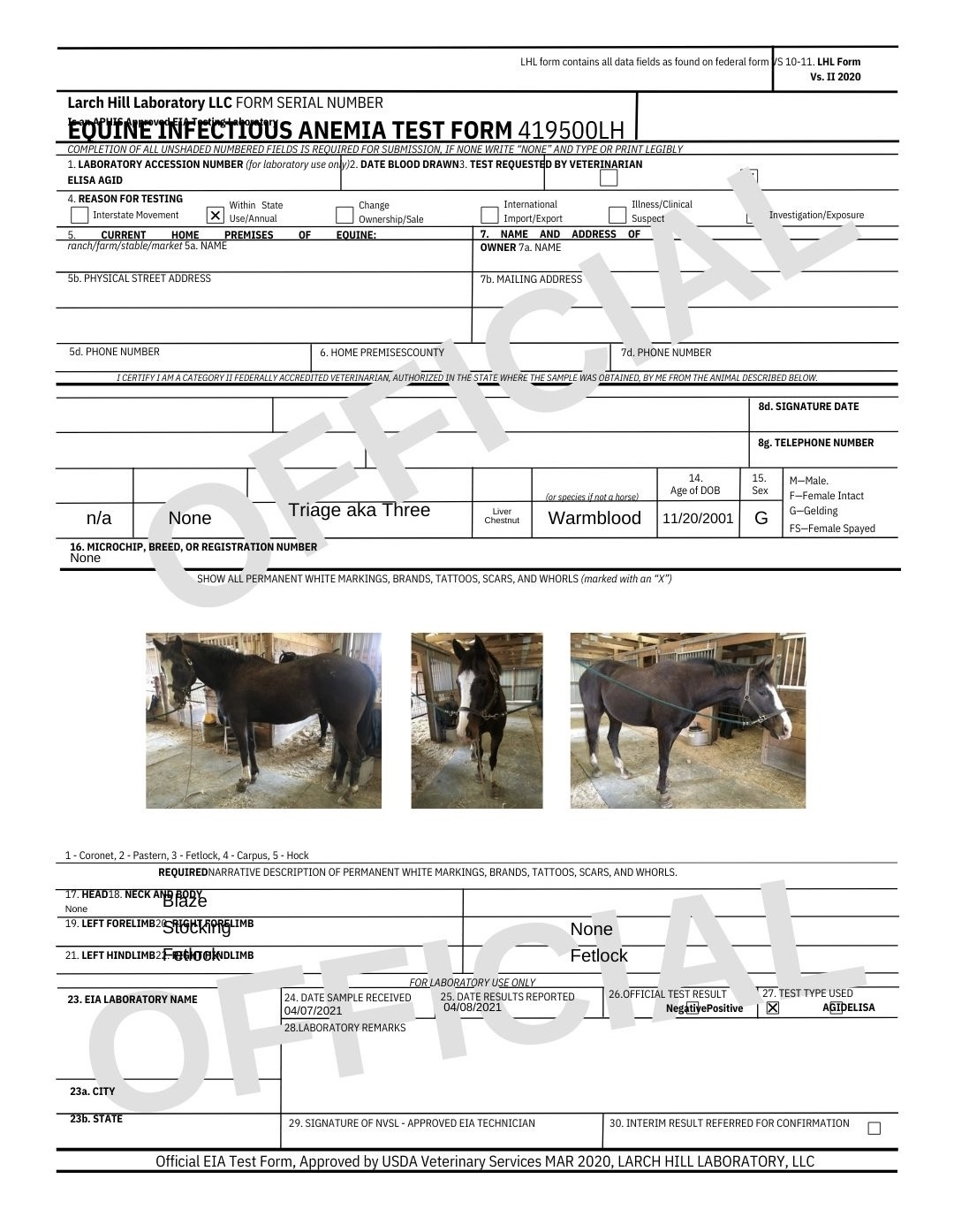

A rare infectious disease affecting horses has reappeared in South Carolina after eight years likely due to the reuse of contaminated needles, according to a state veterinarian. (Photo provided by Mary Margaret Coats)

Mary Margaret Coats was a teenager the first time she performed an intravenous injection. When her horse had a three-day medical emergency, her veterinarian passed the responsibility to her.

“Every six hours, I was up at the barn giving a horse a shot,” said Coats, who rides horses in Raleigh, North Carolina. “I was watched by the vet the first time, and then watched by my parents and the horse trainer the next three times.”

Coats said many horse injections are not supervised by veterinarians. This could leave “room for error.”

“There is going to be that one lazy person that doesn’t want to have to set up the needle, tap it, take the syringe, put it in the vial, all the steps,” Coats said. “And I’m sure they have shortcutted it.”

Experts say those shortcuts could be a factor in the recent outbreak of an incurable disease affecting horses in South Carolina. Equine infectious anemia, also known as Swamp Fever, appeared in the state in August for the first time in eight years. So far, seven horses have been euthanized from the same racehorse farm, said Sean Eastman, a state veterinarian who works for Clemson University and is the state’s lead health investigator in the ongoing case.

Equine infectious anemia can be deadly, is highly contagious and could pose a threat to the state’s lucrative horse racing industry. Surviving horses continue to carry the disease until death and can spread it to other horses unless they are quarantined for the rest of their lives.

Once a horse tests positive for EIA, the result must be reported to the state veterinarian. Horse owners then have three options, according to S.C. law: euthanization, sale for slaughter or research or permanent isolation.

Officials at race tracks, horse shows and rodeos are asked to use disposable hypodermic needles and syringes — one needle, one horse — according to state law. It’s unclear if any fines could be issued or legal charges filed.

The seven horses likely contracted the disease via shared needles, Eastman said.

“I own horses myself, and I can’t figure out why they wouldn’t spend 50 cents on a sterile needle for a $10,000 horse,” Eastman said.

Large animal veterinarian Moira Meyers of Maryland said infection from contaminated needles is becoming a problem for the large horse racing population in South Carolina, Louisiana, Texas and the Gulf states.

Washington State Department of Agriculture animal health officials also confirmed the disease in two horses in October. It was the state’s first outbreak in seven years.

The outbreaks seem to be linked to “bush track” circuits, a term used to describe unsanctioned, informal horse races common in rural areas. Both infected horses in Washington were on bush track racing circuits in Washington and California, the department said in a press release.

If South Carolina’s cases are traced to infected needles, it’s a shame, Meyers said.

“This is frustrating, because it’s kind of a no-brainer,” Meyers said. “I would say your average horse owner knows better than to share needles.”

Tracking down SC’s problem

It’s possible that the cases at the racehorse farm in South Carolina are not isolated. Eastman said that while the facility is currently under quarantine and investigation, it’s possible the disease could have spread to other horses at races. As in the Washington state cases, all the S.C. horses involved are associated with bush track racing, he said.

“It’s been proven and alleged that at these bush track races, horses are injected with performance enhancing drugs,” Eastman said.

While Eastman said the outbreak is probably due to shared needles, it also can spread via insects. However, flies can only transmit 0.0001 virus particles, while a needle carries 100 to 1,000 times that volume, according to EquiManagement. Viruses can also stay alive on a needle for up to four weeks.

Meyers said bush track racing facilities are infamous for taking shortcuts.

“There’s probably at least a small element of laziness,” Meyers said. “It’s faster to just go down the line and medicate these horses without changing the needle and changing equipment.”

Money also may be reason for needle sharing.

“I am aware of some of these race tracks and these race trainers and owners that it comes down to every penny,” Meyers said. “I think a lot of the sharing of needles in those circumstances comes down to money. Every needle costs money, even though it’s not much money.”

There is no vaccine or treatment for the disease, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The symptoms of the disease can be vague at first, Meyers said.

“The horses are weak, lethargic,” she said. “Oftentimes, they’ll have a fever.”

Horses suffering from EIA may experience jaundice, rapid breathing, rapid heart rate, swelling of limbs, bleeding from the nose, red or purple spots on mucous membranes and blood-stained feces, according to the agriculture department. They also may experience sudden death.

A horse can live with EIA but will be forced to isolate from other horses for the remainder of its life.

Meyers said the disease is “uncommon-to-rare,” noting she’s never encountered a case in her 12 years of veterinary experience. Nevertheless, horse owners must screen once a year for the disease using a Coggins test.

“If you have a positive Coggins, you wouldn’t be allowed to leave your farm (with your horse),” Meyers said.

It’s becoming “more and more difficult” to get horse owners who don’t travel regularly with their horses to get a Coggins test, she said.

“People have gotten into the habit of saying, ‘Oh, my horse doesn’t go anywhere, I don’t need to test for equine infectious anemia,’” Meyers said.

However, some horse owners say it’s possible that active, traveling race horses may carry the disease and not have a Coggins test.

Preventing the spread in SC performance horse circuits

Sheldon Hehr grew up on a show horse farm and training facility in Charleston that housed up to 50 horses.

Hehr said horse shows can draw up to 3,000 horse attendees, and the risk for communicable illness is high. For this reason, shows require competitors to provide their Coggins sheet.

“If you don’t have those papers, you can’t get into the show,” Hehr said.

Despite the requirements, Hehr said some horse handlers might find ways around the rules, especially if they have “connections” to the show administrators.

“There’s a lot of gray area,” Hehr said. “It’s hard to sneak in a sick horse, but it has been done.”

Exposing a sick horse to other horses has serious physical, emotional and financial consequences, Hehr said.

“Some of those horses are paying for my college — some of them are pets,” Hehr said. “It’s not like a cold or flu. The next day, they could be dead.”

Some horse professionals in the state’s horse showing and racing communities said the spread of disease from shared needles would be less likely in official, closely monitored circuits.

Raleigh’s Coats said that while she finds the lack of knowledge within the horse caregiver community “shocking,” she acknowledges that not all handlers have the same background she does.

“I could sit here and list 30 different things that could be transferred from horse to horse, from animal to animal, from people to animals — vice versa,” Coats said.

Coats said her barn takes careful precautions to prevent the spread of disease through needles.

“At our barn at least, there are red hazardous containers that have to be present,” Coats said. “When vets come, they make sure you have a hazardous waste place to dispose (of) the needles, and then we have a full box of new needles.”

Despite her own experience with equine medical care, Coats said she knows not all horses receive the same treatment as her own.

“I have been at performance horse barns my entire life, I have traveled across the country, and this is such a professional business that we got ourselves into,” Coats said.

“But there are people everywhere who just want to get a horse like they get a dog. There are a lot of people who are uneducated.”