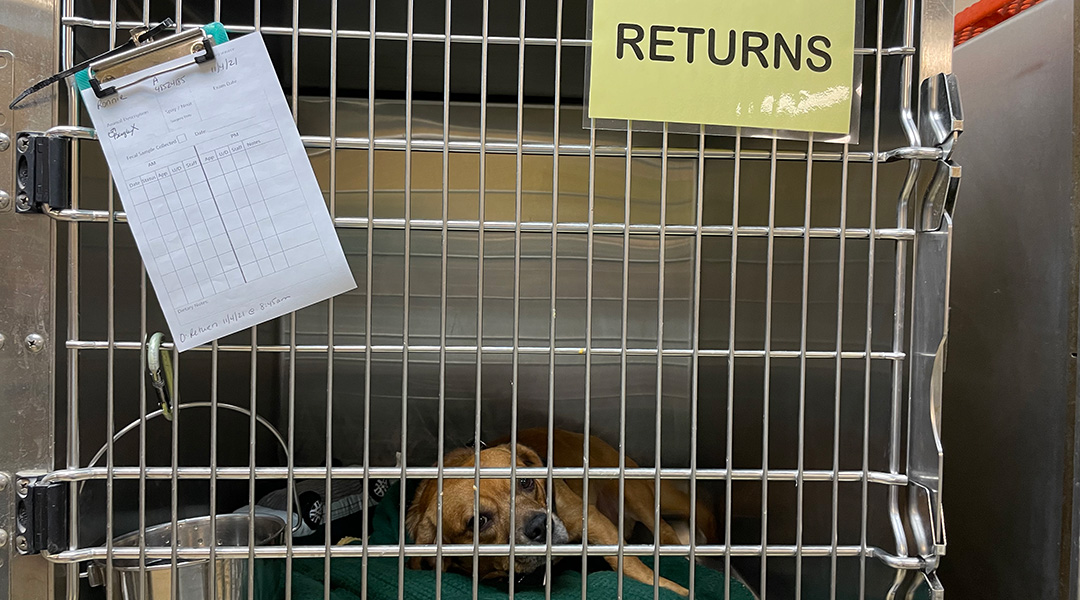

Ronnie, a beagle mix, was returned to Pawmetto Lifeline, the same shelter he was adopted from. Photos by Mackenzie Patterson

As more people head back to work, “pandemic pets” and their problems have become buzzwords to illustrate an issue that doesn’t really exist.

Rumor has it that the pets adopted during the pandemic are unruly, untrainable, and have separation anxiety. Now, as shelters report overcrowding, many place blame on owners who are apparently returning these pandemic pets.

But pandemic pets aren’t the issue. Experts say the animals popping up in these shelters are coming from longtime owners who can no longer afford to care for their pets due to financial troubles caused by the pandemic.

The Humane Society, a national organization seeking to end animal cruelty, said it hasn’t recorded a trend of pandemic pets being returned to shelters.

“Those of us fortunate to share our home with four-legged family members know that giving up a pet would be incredibly difficult — not simply a response to workplaces reopening,” the Humane Society said.

Data from Pet Point, a company that collects national data on animal welfare, confirmed the numbers of animals being returned to the shelters they were adopted from are still significantly lower than they were pre-pandemic.

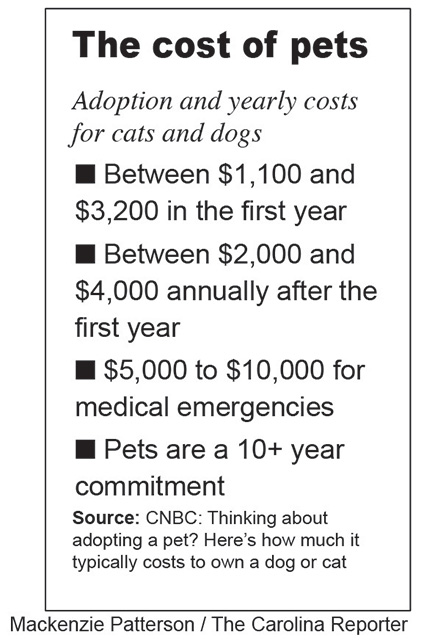

Citing that data, The Humane Society explained that economic hardships and evictions resulting from the pandemic leave pet owners with few options to support their animals. This leads to more surrendered pets.

Pandemic pets are defined as returns, animals that were adopted from and returned to the same shelter after some time with a family. Surrendered pets did not come from a shelter. Instead, they lived with families or were born outside of the shelter and were dropped off by their owners at a rescue when they could not be cared for anymore.

“Many pet families find themselves struggling to afford veterinary care, or even food, for their pets due to the devastating economic consequences of the pandemic,” the Humane Society said.

Pawmetto Lifeline, a nonprofit rescue in Columbia, attribute the surrenders to medical and financial problems owners are facing.

Libba Ulery, who works in adoptive administrative support at Pawmetto Lifeline, said the organization offers resources to pet owners to help them with financial struggles that would cause them to surrender their animals, but that doesn’t convince all owners to keep their animals.

Other problems mentioned were the longer kitten season that resulted from a warmer fall in the Midlands. The high adoption rates in 2020 coupled with low intake rates at the time also contribute to the feeling of overwhelm.

“It’s kind of like the perfect storm, and we have to factor in that during ‘20 with people home, you weren’t seeing as many dogs turned in to the shelters. People were keeping them, people were adopting,” said Ulery.

Another local rescue, PETSinc., also sees lots of surrenders. It currently has a waitlist of people hoping to surrender their animals in an attempt to prevent overcrowding in the shelter so it can provide adequate care to each animal.

“A lot of them are bringing them in because of financial struggles or because, a lot of times it’s like a parent or a grandparent who owned an animal, and their relatives have made the decision to remove the cat or the dog from their home because the elder can’t take care of them anymore,” said Ariel Flowers, a PETSinc. employee.

Kathy Morrison, the media director for PETSinc., said those financial burdens are then passed on to the shelters. PETSinc. is approaching its 30th anniversary as a nonprofit that depends on donors to operate. Donations fund care the pets need, from supplies to surgeries, but the economic crisis and labor shortages affect that area of the rescues’ success as well.

“We’ve had an influx of special needs pets… those kinds of pets are difficult to adopt,” Morrison said. “We try to help them, but we have to incur those surgical costs and the daily care.”

Pawmetto Lifeline and PETSinc. are both hoping that more donations of money and items such as bleach and blankets, will come in soon to help provide care for the heavy intake load.

Surrendering a pet isn’t an easy decision, and the rescue organizations know that. On a tour of Pawmetto Lifeline’s intake rooms, Marketing and Communication Director Maria Wooten said rescue workers can always tell when an animal is about to be surrendered because of how much love the owners are showing them at the rescue.

Rianna Scott, a 20-year-old military wife, surrendered an animal in 2021. She adopted an adult dog in February as a companion for her other dog. When her new pet, Arlo, became aggressive with her other dog, she used every resource she had to keep him in her household.

“He does have these issues, but he’s a really great dog, and it was breaking my heart to even have to think about finding a new home for him,” Scott said.

Arlo went through training, and Scott was hopeful that his behavior would improve, but with time Scott realized Arlo would need to be rehomed. Scott posted multiple times about Arlo on Facebook to avoid returning him to the shelter and eventually found him a new home.

“He was a member of our family. He wasn’t a pet at that point … I miss him and I probably always will miss him. He was, you know, he was like my best friend,” Scott said.

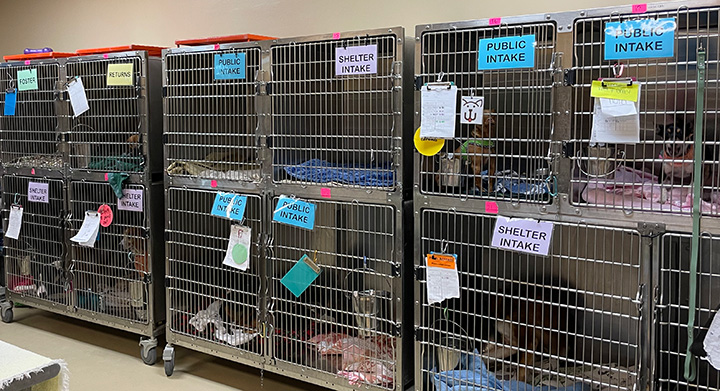

One dog sits in a crate in an overflow room at Pawmetto Lifeline. Pawmetto manages its intake to try to prevent overcrowding.

The kennels in the intake room at Pawmetto Lifeline are full. Kennels marked “public intake” house surrendered animals, and kennels marked “shelter intake” house animals who were transferred from another shelter.

Ariel Flowers, a PETSinc. employee, holds and hugs the animals in the adult cat room at PETSinc.

Many animals at Pawmetto Lifeline and PETSinc. are ready for adoption and greet visitors warmly.