A pair of pointe shoes can cost anywhere from $70 to $100, and professional dancers wear out two pairs a week on average. For ballet companies and dancers, the shoes are a huge expense.

From now until her first performance in Columbia Classical Ballet’s “The Nutcracker” on Nov. 30, Columbia Classical Ballet dancer Mathilde Lambert will spend more than 300 hours in the ballet studio, dancing through around 18 pairs of pointe shoes.

“I’m literally in pointe shoes the whole day,” Lambert said. “I try not go through more than two pairs per week, but usually towards the end of the week I am really struggling. The shoes are really dead and I’m pushing through it.”

Most pairs of pointe shoes last anywhere from three to 15 hours for professional dancers – and cost anywhere from $75 to $100 a pair. The shoes are still largely made by hand in traditional pointe shoe factories. The cost of pointe shoes is driven up by the lengthy process of making a pair.

Lambert attempts to spare expense and lengthen the life of her shoes by applying hardening glue to the box – the part of the shoe that holds the toes – and by rotating her worn shoes and newer ones for class and rehearsals.

A “dead” pointe shoe is one that has been entirely broken down by a dancer’s foot. Before a shoe reaches this stage however, it must be “broken in,” a process in which a dancer makes new, stiff pointe shoes her own by manipulating them to fit her foot. For some dancers, this means softening the box of the shoe in a doorjamb, while others may “darn” – add stitches – to certain parts of the shoe or break down certain areas of the shoe with other tools.

“My feet are not very good so I do a lot to my shoe and I need to make the shoe fit me,” Lambert said. “I darn only the outside of the top of the box, so I can get up on the shoe. Sometimes I sew the side of the shoe to make that thinner and show more of my foot. Then I cut the sole in half with the X-Acto knife on both the inside and outside.”

Once a shoe is broken in, it only lasts a brief amount of time before the cardboard and glue inside the shoe begins to completely disintegrate, forcing a ballerina to buy a new pair of shoes. For someone earning professional dancer’s pay – on average $14.25 an hour according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2017 – the constant need for shoes can be a huge financial burden.

While some larger companies offer unlimited pointe shoes to their dancers, most mid-sized companies can afford to pay for around 80 pairs of shoes a season for each dancer, and even smaller companies like Columbia Classical Ballet can only afford to pay for part of the cost of each pair of shoes.

“It’s a huge expense, and our pointe shoe budget is not nearly enough for what the dancers need,” Columbia Classical Ballet Artistic Director Radenko Pavlovich said. “We want to provide as many pointe shoes for the dancers as possible because it is such a vital part of their life.”

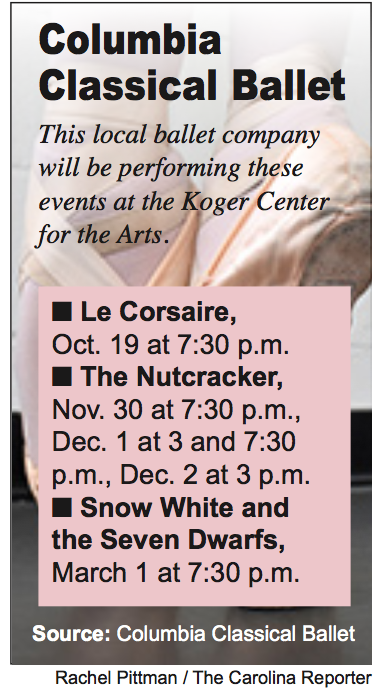

Pavlovich said that pointe shoes are one of the main expenses of the company, and one of the main expenses for Columbia Classical dancers personally. The company hosts in-studio performances to raise money for their pointe shoe fund, and also partners with local dance store Turning Pointe to defray shoe costs.

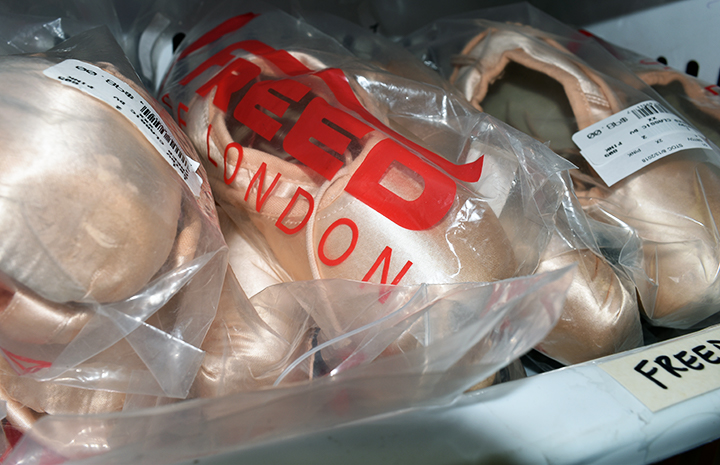

Turning Pointe has been in business for over 35 years, and is one of the only shops in the Midlands that sells pointe shoes. The store carries 25 to 35 styles of pointe shoe made by eight different brands, including – Grishko, Russian Pointe, Bloch, Capezio and Freed of London, a classic brand that Lambert and many other professionals choose. Coleen Strasburger is the owner of Turning Pointe, and she recommends prepping pointe shoes early to attempt to make them last longer.

“Once the shoes are dead, that’s it,” Strasburger said. “You have to prepare ahead of time. If your box breaks down a little at the beginning of a wear, go ahead and jet glue that to harden it in advance, and try and rotate your shoes too. Don’t leave any toe padding in the shoe because that leaves the moisture in the shoe and it’s all paper and glue.”

There is only so much a dancer can do, however, to preserve the life of the shoe. Classical ballet is an art form firmly rooted in the past, and the pointe shoe industry is similar in its tradition.

The probability that the intricate method of construction or technology behind the short-lived slippers will change is slim, and ballerinas must pay the price that is required to have the necessary footwear.

“In the end it’s so worth it to always prepare and pay for new shoes,” Lambert said. “You can’t dance if you have bad pointe shoes, it’s impossible. You can’t turn, you can’t jump, you feel bad. It’s so important to have the right shoe. It’s like having a second skin.”

Mathilde Lambert, 19, is a dancer with Columbia City Ballet. She tries not to use more than two pairs of pointe shoes a week due to the cost, and normally has to dance on dead pointe shoes by the end of the week.

Dancers must sew ribbons and elastics onto each new pair of shoes they buy. Some dancers choose elasticized ribbon rather than satin to ease tension on the Achilles tendon.

Freed of London is one of the most popular brands of pointe shoes among professional dancers. Turning Pointe carries this English brand of shoe.

Columbia Classical Ballet is a small ballet company in the Midlands. Dancers Jinsol Eum, left, and Nao Omoya, right, are rehearsing for the company’s upcoming performance of “Le Corsaire.”

Preparing pointe shoes for use is a lengthy process. Dancers must sew ribbons and elastics onto the shoes and also soften the box and shank – or sole – of the shoe to their personal liking.