Kinship Care Initiative was founded in 2014 by the Sisters of Charity Foundation to work with other programs to fund grants and offer support for kinship caregivers and their families.

Thousands of South Carolinians are stepping up to take care of grandchildren, nieces and nephews who would otherwise be placed in foster care because their parents could not take care of them, including the mother of famed Gamecock football standout Marcus Lattimore.

“I sacrificed everything that I knew for me, for them,” Lattimore’s mother, Yolanda Smith, told a State House gathering Tuesday. She and other advocates are asking the legislature to provide funding to assist these guardians. Smith cared for a niece and nephew.

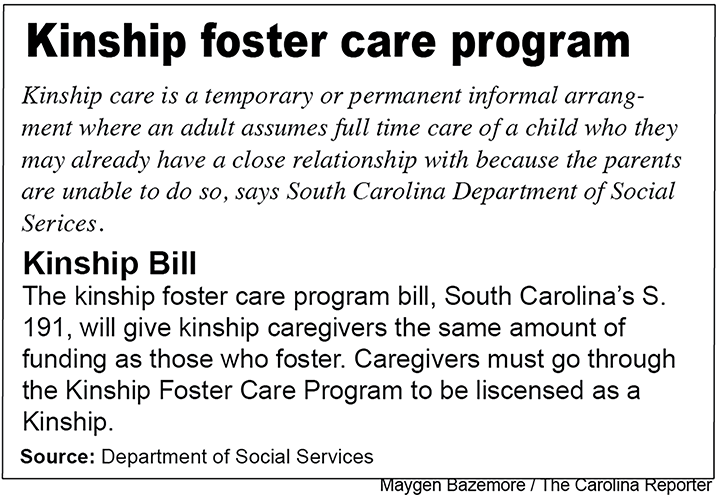

According to the S.C. Department of Social Services, kinship care is a temporary or permanent informal arrangement in which a relative or non-related adult has assumed the full-time care of a child whose parents are unable to do so. These caregivers may already have a close relationship or bond with the child or family.

“There are over 50 thousand families that are taking care of kids that aren’t their own,” said Tom Keith, president of the Sisters of Charity Foundation, a Roman Catholic nonprofit. “We need to take care of those individuals and their families.”

Now some state legislators are stepping up to provide financial help.

A bill introduced by Sen. Katrina Frye Shealy, R-Lexington, would provide kinship caregivers the same amount of funds that foster parents are given. The legislation has made it through the Senate and is now in a House committee.

Foster families receive anywhere from about $400 to $550 a month, depending on the age of the child. Currently, kinship families may obtain some private help from non-profit organizations, including HALOS, a Charleston organization that provides funding to aid kinship families, and the Kinship Care Initiative founded in 2014 by the Sisters of Charity.

Smith, who was raised by her grandmother and then went to raise other family members, said she recognizes the sacrifices kinship families make.

“I worked whatever job I could in order for these kids to have a life that they deserved… Along the way, I finally realized, I’m doing the exact same thing that my grandmother did,” Smith said. “I’m taking care of these kids without any help.”

“There wasn’t a Kinship Care. There wasn’t a HALOS Project,” Smith said. She said she found networking opportunities and friendships that helped her raise her three biological children and her niece and nephew, who are all successful college graduates today.

According to Keith, the Sisters of Charity’s Kinship Care Initiative contributes funds and provides emotional support to multi-generation households.

“There’s a generation switch there,” he said, so that grandparents may have to learn the latest computer programs to assist grandchildren with homework.

Benzina Alleyne, of Charleston, cares for three grandchildren and faces some financial difficulties.

“When you’re a single parent and trying to raise grandkids, it’s very difficult. It’s hard for me,” Alleyne said. She believes that the bill could help caregivers by providing funds for clothes and food as well as health care costs and education.

“A mother or father or both parents can’t take care of the kids for whatever reason, they leave them with a grandparent or an aunt and an uncle and they become the primary caregivers… it happens a lot, and often times, the individuals that are taking care of the children are struggling financially,” Keith said.

“We’re looking for ways here and have asked our friends in the legislature to help us with some funding to take care of these families more effectively,” he said.

“Now that you’re here today, this is another monumental step for you to come and advocate and celebrate together,” Rep. Neal Collins, R-Pickens, said at the rally. “We want to hear what issues are affecting communities and, serving a children’s committee, I know that kinship caregiving is one of those.”

Tom Keith, president of the Sisters of Charity Foundation, says there are more than 50 thousand families in South Carolina that are taking care of kids that aren’t their own. “Often times, the individuals that are taking care of the children are struggling financially,” he said.

Yolanda Smith, former Gamecock football player Lattimore’s mother and a kinship caregiver, says she was a single parent of five children with one income. She recognized the sacrifices her grandmother made to raise her when she started having to make those sacrifices as a caregiver.