Cotton Branch Farm Animal Sanctuary’s main goal is to socialize pot-bellied pigs for adoption. They also house other farm animals on the sanctuary in Leesville.

LEESVILLE, S.C. — About 40 minutes outside of Columbia down a dirt road, around 300 pigs, horses, goats and a 2,000-pound cow named Freckles freely roam a farm animal sanctuary established to socialize some animals for adoption and to house others as permanent residents.

Leaders at Cotton Branch Farm Animal Sanctuary want to do more than care for the animals and find some of them new homes. They helped run Impact 2020, a farm animal rescue conference, in Columbia on Feb. 22. People from farm animal sanctuaries around the country attended, with some coming from as far away as Pennsylvania and Kansas.

At the summit, sanctuaries exchanged strategies for socializing and raising animals for adoption. They also discussed how to set up legal boards of directors to oversee sanctuaries, how to fund-raise and how to be transparent.

“For so many people, it’s not picketing or protesting or beating people over the head with anything,” said Josh Carpenter-Costner, the president of Cotton Branch. “Meeting an animal and making a connection is why people fall in love with dogs when they first meet them.”

Most of the animals on the 21-acre property were rescued from a northern Kentucky farm. That farms few original pigs were neglected and overbred, resulting in malnourishment and inbreeding. Cotton Branch worked with other farm animal sanctuaries to rescue more than 450 pigs, mostly companion pot-bellied pigs.

Cotton Branch had 225 of the Kentucky pigs, but has adopted out 75 in the year since. Their goal is to adopt out the last 100 pigs that can leave the farm for more permanent homes. Fifty have to stay on the farm as permanent residents due to disability or old age. Cotton Branch has also helped save animals from two other major hoarding cases to further increase their numbers.

Josh Carpenter-Costner and his husband Evan Costner, the executive director, took over the non-profit Cotton Branch in 2018 with a goal to expand the reach of the sanctuary. Because there is no federal or state funding for farm animal sanctuaries, they rely entirely on donations, grants and volunteer workers.

The farm’s main goal is to socialize pigs for adoption.

“We’ve been amazed at how quickly the pigs are coming around now that people are visiting them and spending time with them every day,” Carpenter-Costner said. “It used to take about a month for them to go from frightened of people to being petted, now we seem them going from hiding to getting belly rubs in a week.”

Cotton Branch works with other sanctuaries across the country to rescue pigs and other farm animals from neglectful and abusive situations. In 2020, the goal is to increase their outreach and education efforts and help new sanctuaries to get more pigs adopted and other fam animals saved.

One obstacle in getting pigs ready for adoption is the stigma that people in the United States have against farm animals. Ninety-eight percent of animals killed every year in the United States are farm animals, but many animal sanctuaries do not accept them, which puts the burden to fill the need on farm-animal-only sanctuaries, according to Carpenter-Costner.

“We see them already packaged as food and people don’t really meet them and see them as individuals,” Carpenter-Costner said. “As people come out and meet them, they see them a lot differently.”

According to Carpenter-Costner, pigs are much more than prepackaged food. Pigs have the intellect of a 3-year-old child and are the fifth smartest animal, humans included.

“I tell people they’re kind of like a combination of a cat, a dog and a toddler,” Carpenter-Costner said. “They want attention like dogs, but they’re not usually 24/7 under feet like dogs, so they’re more independent and curious like cats. They pout, they get angry, you can tell when they’re happy, so they’re kind of like a toddler in that respect.”

Carpenter-Costner grew up around farm animals and never saw them as any different from “normal” companion animals like cats and dogs. Some of the pigs at Cotton Branch that are permanent residents due to being older or having disabilities have their own bedrooms and rules.

“It seems like they really understand things when you’re talking to them,” Carpenter-Costner said. “I can threaten a timeout and they behave. If they get a timeout, I set a timer, and when it goes off they know that means they can come out.”

Carpenter-Costner said Cotton Branch uses volunteers to help socialize the pigs and keep up with daily chores. Volunteering can have an impact on the people helping and not just the pigs.

“It calms me down a lot,” said Amber Colacchio, a Columbia resident who has volunteered at Cotton Branch a few times. “It feels good that I’m contributing something. It feels small, but I’ve seen these pigs’ attitudes change. I’ll go one week and a pig that wouldn’t even get near anybody is running up to you wanting to be fed. I feel very connected to them already.”

Cotton Branch’s leaders say breeders don’t bring anything special to the table in the world of pig adoption and that their pigs are just as good once socialized.

“We educate people with how many pigs need rescue and need homes,” Carpenter-Costner said. “You don’t need to go to a breeder to get an animal. They’re not going to sell you a pig that is any different than you could adopt from us.”

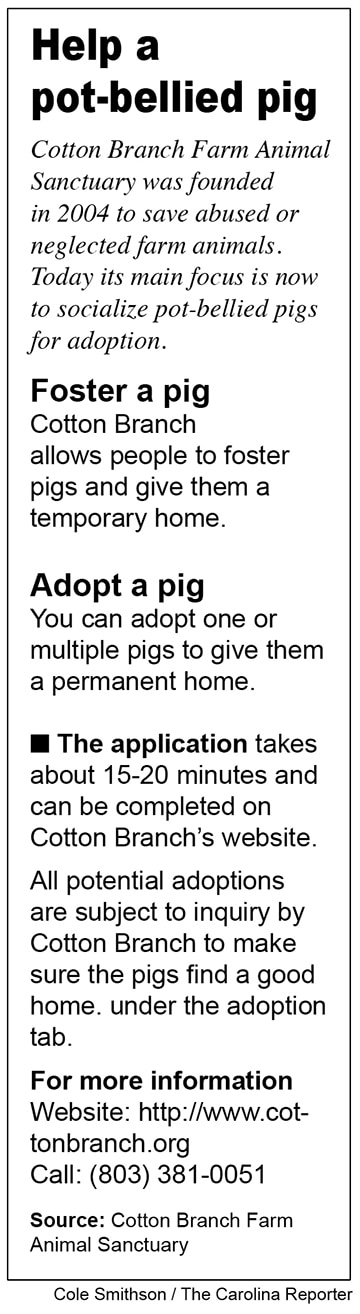

If you want to adopt a pig, visit Cotton Branch’s adoption tab on their website: http://www.cottonbranch.org/adoption.html.

Josh Carpenter-Costner, president of Cotton Branch Farm Animal Sanctuary, plays with Ellie Mae, a 90-pound pot-bellied pig that loves attention.

Handicapped pig Teddy has a genetic degenerative leg condition that made his back legs stop working, but his wheelchair lets him get around the farm.

Cotton Branch is home to over 200 pigs and the organization is trying to get at least 100 adopted in 2020.

The pigs that are socialized at Cotton Branch are not scared of people and love attention.

Teddy’s back legs stopped working shortly after he arrived at Cotton Branch and he’s been in his wheelchair they made for him for about a year.