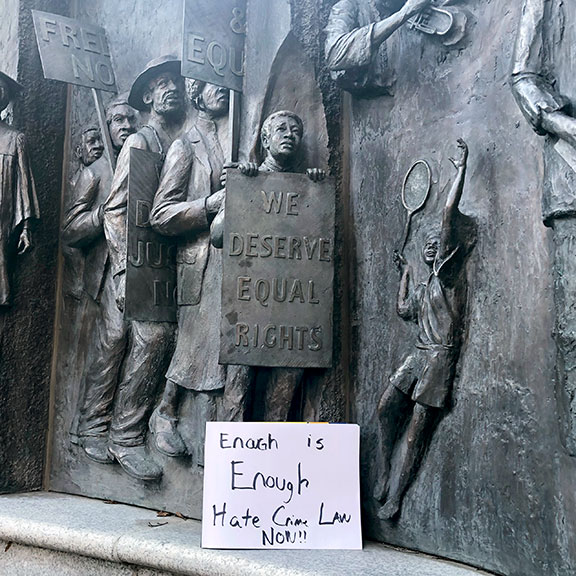

South Carolina is one of only three states that has not passed an additional law against crimes motivated by prejudice against race, religion, gender identity or sexual orientation. Photos by: Ryan Ducey

Almost 100 South Carolina businesses asked the state this week to pass an anti-hate crime law at a virtual press conference hosted by the South Carolina Chamber of Commerce.

South Carolina is one of only three states that does not currently have an anti-hate crime law. These businesses hope that applying economic pressure will encourage legislators to pass one.

“[This is] an opportunity… to speak out loud and in a united voice against hate and the brutality it breeds,” said Wamart’s Public Affairs Director Brooke Mueller during the press conference. “We will actively work to support this legislation to see that [the anti-hate crime bill] becomes law.”

The Chamber of Commerce has used similar strategies to make significant progress in the past. In 2000, foreign companies, led by German vehicle manufacturer BMW, forced legislators to remove the Capitol dome’s Confederate battle flag.

More recently, the Greenville-based Michelin forced the state to increase its gas taxes by two cents per gallon in 2017, after the tire company threatened to pull out of South Carolina entirely.

Like removing the Confederate battle flag and upgrading the state’s roads, the passage of an anti-hate crime law in South Carolina is seen by many as long overdue.

The current bill, which proposes harsher penalties for crimes motivated by hatred for racial identity, sexual orientation, gender, religious beliefs or disability, was initially drawn in 2015. It took five years to gain enough traction to reach the General Assembly floor, despite bipartisan support and outspoken advocacy from S.C. House Speaker Jay Lucas.

The bill now sits on the General Assembly floor, with no current motions or plans to vote upon it soon.

The hold-up may partially result from the negative reaction to the hate speech ordinances placed in cities like Columbia, Charleston and Greenville over the last two years.

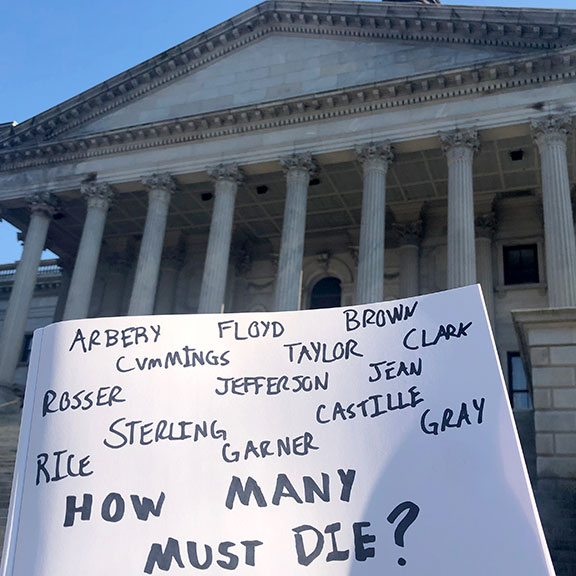

According to various city council members, these ordinances were put in place as a direct response to South Carolina’s lack of an anti-hate crime law and in the wake of protests over police brutality and the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breanna Taylor and George Floyd. However, instead of discouraging hate crimes and hate speech, the ordinances had the unintended effect of incriminating multiple homeless people of color.

“[The city took] it to the extreme,” said Nathaniel Robinson when asked about the enforcement of the hate speech ordinance in Columbia.

Robinson is a lawyer who represented several homeless people charged with hate speech offenses.

A review conducted by the Post and Courier in Charleston found that 86% of all criminal charges invoked by the hate speech ordinance in Columbia came against people of color.

Such missteps have made several conservative state representatives hesitant to pass the bill into law. They fear an even stronger law will lead to unfair punishment and potential violations of individual rights.

“The main concern is this whole idea of prosecuting people for their thoughts, ideas and beliefs,” said Rep. Garry Smith, R-Simpsonville. “This is very much a chilling and disturbing proposition.

However, despite the reservations of Garry and others, the bill appears to be gaining momentum with lawmakers and the Columbia community.

On Feb. 25, a group of college students from the Columbia area gathered on State House grounds to advocate for the bill’s passing. The students carried posters and stickers and seemed hopeful that South Carolina might soon turn a corner regarding its hate crime legislation.

“It’s insane that it’s taken this long, but I think it’s finally about to become a reality,” said Zoie Lagoudis, a 22-year-old student at the University of South Carolina that arrived with the group. “Money talks.”

While many are relieved that the bill may finally become law this year, some legislators are concerned by the process’s length. They also fear that progress only occurred due to the Chamber of Commerce’s actions, potentially setting a delicate political precedent.

“The voice of corporations carry more weight than the citizens of South Carolina,” said Rep. Justin Bamberg, D-Bamberg, in a tweet on Feb. 23.

Currently, the bill waits for a House committee hearing. In the meantime, the Chamber of Commerce has created a website and social media campaign to further publicize and advocate for the bill’s passing into law.

Wal-Mart, which employs over 30,000 South Carolinians, is one of many corporations asking state legislators to pass an anti-hate crime law.

The current anti-hate crime bill was originally proposed in 2015, but took several years to gain enough support to reach the General Assembly.

The bill has become increasingly popular in the capital city area. Students have created several posters to advocate for the passing of the bill.