There’s a new wave of thinness and diet culture sweeping social media, and nutritionists and mental health professionals are worried about the effects on younger users. (Graphic by Reagin von Lehe)

The peak of Lola Hansen’s eating disorder involved her dipping cotton balls in orange juice and ingesting them in order to feel full. She was trying to match body images she saw on Tumblr, a social media app popular in the mid-2010s.

She was 12 years old.

She said she would scroll for hours on Tumblr looking at pale skin, protruding collar bones and thigh gaps.

“That’s what Tumblr was — inspiration for you to be super, disgustingly and sickeningly skinny,” said Hansen, now a sophomore at the University of South Carolina.

Then, in the late 2010s, she noticed social media change, with messages of body positivity. Hansen recovered from her anorexia. But she’s worried for her younger sisters, as social media has recently regressed to an obsession with thinness.

Around 2014 marked the height of Tumblr and the return of the ’90s grunge aesthetic with flannels, overly distressed jeans, Doc Martens and messy buns. With the seemingly innocent nostalgia of the decade also came a return of the “heroin chic” trend. This was famously illustrated by a thin Kate Moss with her ribs showing, dark circles under her eyes and a cigarette in her hand.

Recently, Kim Kardashian boasted about rapidly losing weight, and models such as Bella Hadid are once again being celebrated for their tiny frames and late ’90s and early 2000s fashion is making a major comeback. Heroin chic, cocaine skinny and waif beauty standards are returning with it.

Experts initially attributed the rise of “diet culture” to the pandemic because lockdowns increased social media use, which brought viral posts on dieting and body image.

The International Journal of Eating Disorders shared a survey in July 2020 showing that patients diagnosed with anorexia, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorders “experienced a worsening of symptoms as the pandemic hit.”

Caroline Green is a dietitian in Columbia. She said her private practice and those of her colleagues are now seeing a wait list.

“There has definitely been an increase in eating disorders,” Green said. “It’s just another unattainable beauty standard that we’re being inundated with — pressuring young girls to lose weight and manipulate their bodies to fit what’s on trend and in style.”

A diabetes drug already in short supply vent viral on social media as an appetite suppressant.

“These (celebrities and influencers) … have millions and millions of followers on social media,” Green said. “People are going to unfortunately do what they want to meet that (trend). And it can absolutely wreak havoc on someone’s relationship with food.”

Around 24 million people in the United States suffer from an eating disorder, according to 2021 data from the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders. Eating disorders are reportedly among the deadliest mental illnesses, resulting in more than 10,000 deaths each year.

“(Extreme dieting) was just kind of shoved in your brain, and you couldn’t really get it out no matter what you wanted to do,” Hansen said. “It was just like social conditioning. Everyone was starving themselves, so why weren’t you?”

Hansen said her symptoms subsided with therapy, medicine and a social media movement that pushed back on the thin trend of 2014. The “body positivity and neutrality movement” began in the late 2010s. It praised diversity in women’s bodies and helped Hansen recover.

Artists and celebrities such as Lizzo, Meg The Stallion and Ashley Graham, celebrated their larger bodies and different body shapes.

“(Lizzo is) all about being like, ‘Well, hey, I’m big, but I can still do all of these things,’” Hansen said. “I still eat healthy. I still workout. I still take care of myself. It’s just who I am. … I think that helped me be more comfortable in my body.”

Green said her patients have shown showed improvement during the body positivity trend.

“Just normalizing that there are many shapes and sizes, … they find benefits when they see people that look like them,” Green said. “Representation that shows people in larger bodies that are happy and successful and confident — that’s what we need more of.”

Celebrity personal trainer Jillian Michaels has argued that people shouldn’t celebrate unfit bodies and famously criticized Lizzo and her influence.

Green said the argument is baseless.

“We just can’t tell someone’s health by the size and shape of their bodies,” Green said. “We know that (Lizzo) crushes her performances on stage. She’s running around for hours, so she might have good cardiovascular fitness. Having more of a ‘health at every size approach’ isn’t glorifying.”

And Green said stigmatizing someone’s weight can do more harm than good.

When her patients were able to take focus off weight, she said they were able to tune into their bodies and find what makes them feel their best. From what she has seen in her practice, long-term healthy habits are hard to achieve because people usually set themselves up for failure.

When people focus on their weight and measurements, they don’t see immediate progress unless they practice extreme dieting. This isn’t sustainable, and eventually people either give up and return to previous unhealthy habits or they develop an eating disorder, Green said.

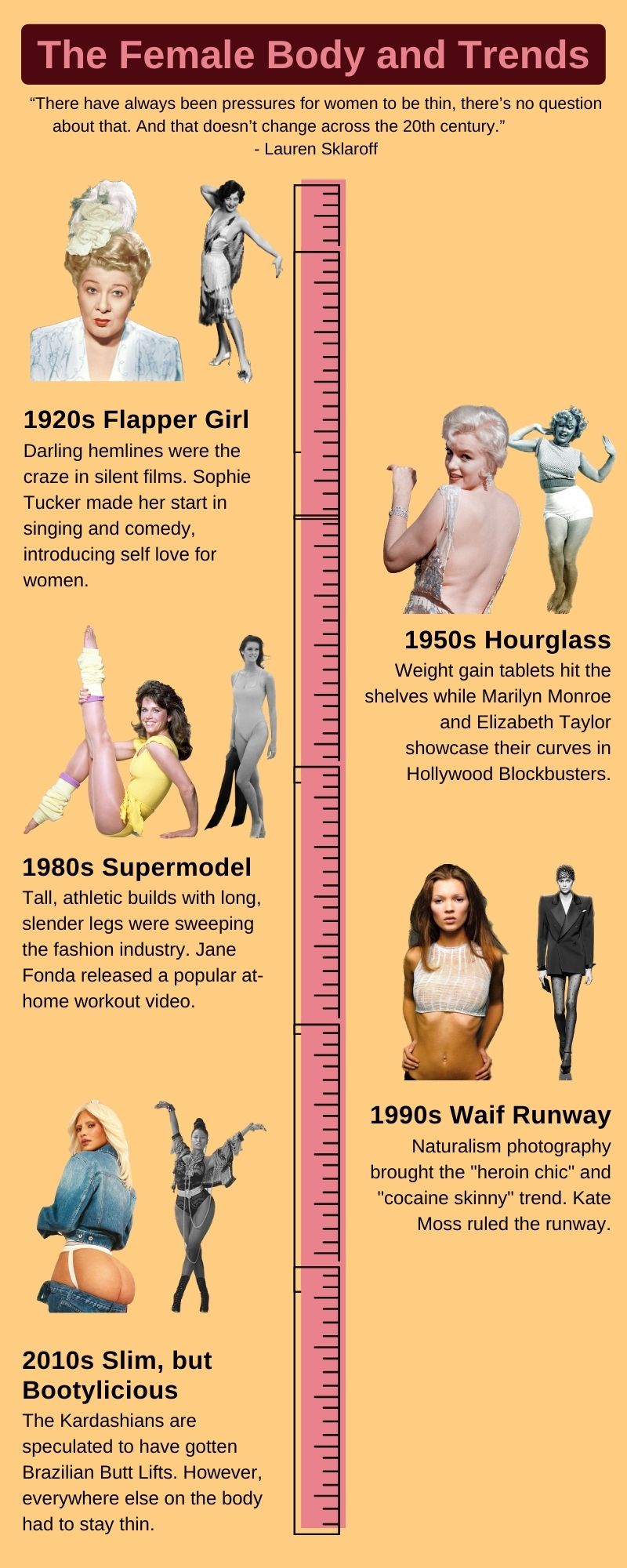

USC professor of History and Gender Studies Lauren Sklaroff said women’s bodies have been treated like accessories for centuries — and have been manipulated to appease social norms.

She wrote a biography on Sophie Tucker, who gained popularity in the 1920s as the first known female performer to embrace her bigger frame.

Sklaroff said there is a difference between the era of Tucker, who made fun of her weight, and that of Lizzo, who embraces hers.

“There have always been pressures for women to be thin, there’s no question about that,” Sklaroff said. “And that doesn’t change across the 20th century.”

However, how that thinness is achieved has changed in each decade.

In the 1950s, Marilyn Monroe had a small waist, but she popularized the curvy, hourglass shape. Jane Fonda embodied the fit and athletic body of the ’80s with her successful at-home workout video. Kate Moss ruled the runway in the ’90s with minimal makeup and a seemingly unhealthy waif look — heroin chic.

By the 2010s, women were taking control over the perception of themselves and their appearances, Sklaroff said. Hence, the body positivity movement.

Lizzo released her Yitty shapewear line for all sizes this past April.

“There is a wave for more kinds of women to find branding or products that meet their needs,” Sklaroff said. “I think that’s really important. That’s the biggest change since Sophie’s day — more women are in charge.”

During today’s body positivity and neutrality movement, celebrities such as Lana Del Rey and Demi Lovato, who previously struggled with eating disorders, went through recovery.

Kayla Orefice, 23, said her road to recovery from anorexia was easier seeing big names go through what she did.

She started struggling with her eating disorder at 12, the same age Hansen did, during Abercrombie and Fitch’s reign in fashion. She said she’d go to the mall with her friends and see huge posters of women with thin bodies.

Orefice said it was the most popular store, but their large sizes fit more like smalls, and it seemed there were more jeans available in double zeros than any other size.

She references the documentary on Abercrombie and Fitch released in 2022, which explored how the corporation “thrived on exclusion” of bigger bodies and darker skin tones. Its ideal standard was “all American,” with tanned skin and thin frames.

“The pressure to wear the cooler clothes … and realizing it’s not made for me was super, super stressful,” Orefice said.

Orefice said she has gaps in her memories from high school because her body didn’t have the energy to retain information with her low-carb and calorie intake diets. At one point, she weighed 110 at 5-foot-4. She said she ate one meal a day, and survived mostly on granola bars and water.

She said medicine, therapy and a better understanding of social media have improved her mental health issues.

Nevertheless, she, Hanson and Green say they are worried about the new generation that grew up on the internet and seem to be more chronically online than previous ones.

“I know who I am, and I’m mentally strong enough to be, like, ‘That’s stupid,’” Orefice said. “But I’m worried about the kids who are in middle school and who are going to start seeing this again and that cycle repeating itself.”

Twitter recently banned the use of the #thinspo hashtag, but others such as #fitspo, #whatieatinaday and #bodychec have taken its place. Influencers on TikTok also are posting videos of themselves examining their figures.

“Unplug,” Orefice said. “Unplug yourself. … It was so toxic seeing constantly just a mirage of models and the Kardashians. Take a day to just sit with yourself and do things that make you happy. And shut off that part of your brain that’s like, ‘I need to be perfect to other people.’”

If you or someone you love is struggling with an eating disorder, you can get help. Call the National Eating Disorder Association helpline at (800) 931-2237 or visit nationaleatingdisorders.org.