The Nickelodeon Theater on Main Street in Columbia hosted an aphasia community event on Oct. 14 by screening “Aphasia the Movie.”

Carl McIntyre struggles to put words and meanings together, a daily exertion that he says is like working through a brain fog. He is a stroke survivor who suffers with aphasia, a disability that is often painfully invisible.

Aphasia is a language disorder that makes it difficult to speak or understand others’ speech due to brain damage. Stroke survivors who have developed this disorder may also have trouble reading and writing. Strokes tend to occur in the same area of the brain and are typically unilateral, meaning they are mostly located in the left hemisphere, according to Leigh Ann Spell, associate director of the University of South Carolina aphasia lab.

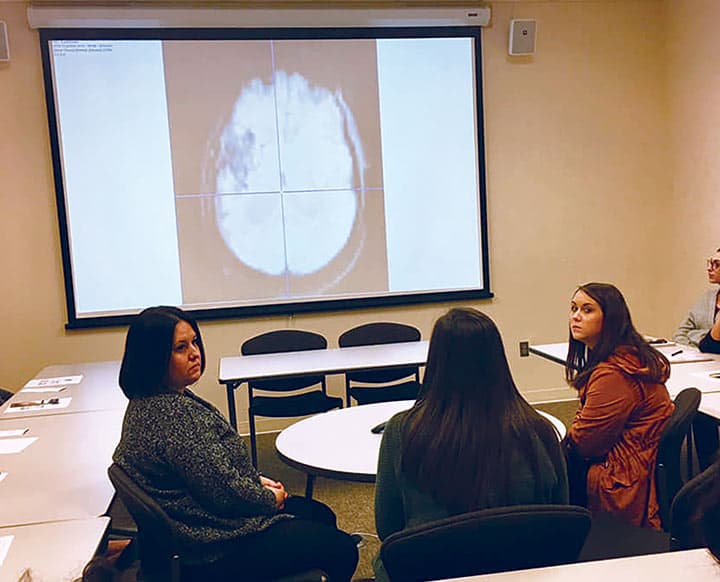

The UofSC aphasia lab focuses on how the brain heals itself. The lab takes detailed pictures of the brain in hopes of understanding how the residual brain works after stroke. The research results show the lab what they can do to promote recovery.

Lab director Julius Fridriksson said a lot of times people with aphasia don’t show strong physical signs of the disorder. Even when people can’t talk, people with aphasia and others around them don’t always notice it. Aphasia is an invisible disability.

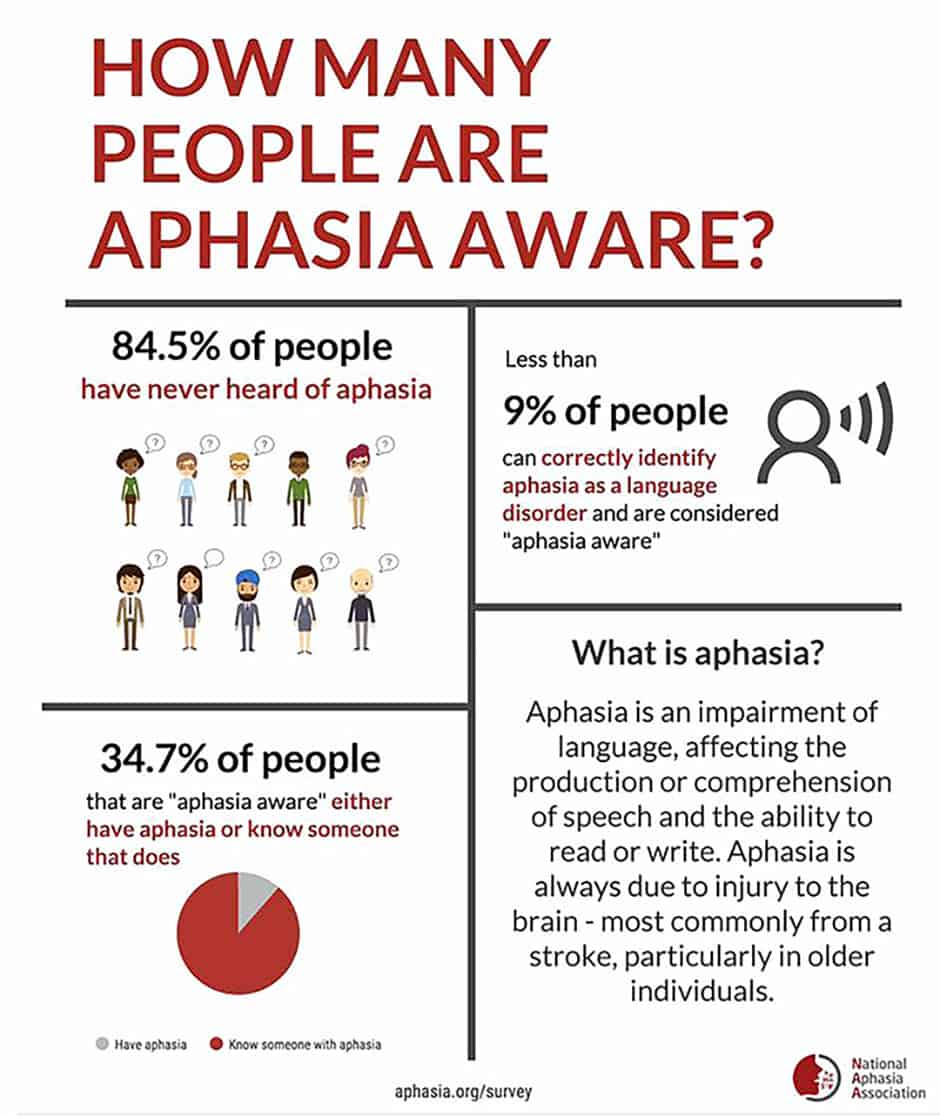

“Aphasia is probably one of those things that nobody knows about even though stroke is the number one cause of disability in the United States. It is extremely common,” Fridriksson said. “In South Carolina, we are the only state where half of all strokes happen in people under the age of 60.”

To spread awareness, the UofSC aphasia lab hosts community outreach activities to treat those diagnosed as aphasic. In October, the Nickelodeon Theater on Columbia’s Main Street participated in a community partnership with the aphasia lab by screening “Aphasia the Movie”, putting on a performance by the lab’s aphasic drama group and having a panel discussion that featured the film’s main character.

McIntyre, of Charlotte, North Carolina, played himself in “Aphasia the Movie.” He survived a chronic stroke in 2005 and wanted to share his story with the world.

“Having a stroke sucks. Aphasia really sucks. Before I had a stroke, life was really good, a wonderful life,” said McIntyre. “Job is voice. Actor, teacher and really good sales. Golden tongue. But after stroke, everything is different now. I can’t talk, write or read.”

The doctor advised McIntyre to wait one and a half years to see improvement. Once the time came, he was not any better. This realization was not ideal for him.

“What?! I need to work, I have to work. It was a low, low time. I’m frustrated, I’m angry. World angry. Why me? Why now? I’m young. I’m trapped in the head. Prison,” said McIntyre. “Disappointments every day, every minute, every second. Depression is really bad stuff. I remember saying, ‘Live or die, I don’t care, I’m fine. Dark place, really dark place.”

McIntyre did not want to give up on life. A couple steps that McIntyre personally took to get out of the dark place he was in after the aphasia diagnosis included:

- Mourn. “First, I need to fix it and fix me,” said McIntyre.

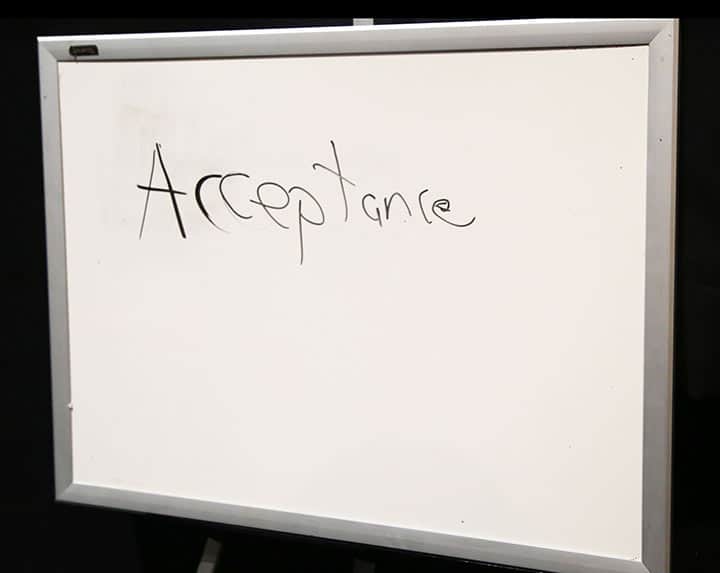

- Acceptance. “Maybe no speaking again but I’m still here. I’m still relevant and no fear, fearless,” said McIntyre.

- Hope. “Hope is everything. No hope, no life,” said McIntyre.

- Purpose. “Big or small, but purpose every day. I love to garden plants and tomatoes, big juicy tomatoes. I love it, but I need more. My purpose is movie and understanding aphasia,” said McIntyre.

Though aphasia has affected McIntyre’s life negatively, he still tries to see the good in the world.

“I know I’ll never think the same but every day is good. Possibilities are endless. I never quit, I never will. I’m living a dream right now. Aphasia still sucks but I win every day and you can too,” McIntyre said.

Spell said many folks that come to the lab can’t get across what they are trying to say.

“I think what makes it so frustrating for them is that they are kind of trapped. They are still the same person but they just can’t express themselves like they used to,” Spell said.

McIntyre is a prime example in this case. He said himself that every stroke is different and there is no magical pill.

“People’s cognitive skills may still be intact where their memory, attention and their ability to organize information is fine,” said Spell. “But some of our participants are pretty fluent. They have a mild aphasia where they have occasional word-finding problems. Usually they can get their point across, whereas other people may be totally nonverbal.”

On the assessment spectrum, McIntyre has chronic aphasia and this is when people tend to seek intensive therapy. Therapy does not need to be at a hospital or with a speech pathologist, one stroke survivor with aphasia told the theater crowd. Someone suffering with aphasia can set a goal to learn a new word by themselves every day.

“For the first year of stroke, I bought tapes of vowels. I’m an actor and I love to rehearse, rehearse, rehearse,” McIntyre said.

Chuck Bludsworth, one of the filmmakers, said McIntyre rehearsed the speech he gave at the Nickelodeon Theater three times even though he had given the speech professionally nearly 100 times.

After five years of therapy with his speech pathologist in Chapel Hill, McIntyre does not attend therapy anymore. Speaking, talking and listening every day is his therapy, he said.

Lynsey Keator, the lead coordinator for the aphasia community event, said the event at the theater is meant to not only raise awareness, but to share research and bring together a group of people who all share this communication disorder.

“My hope is that in my lifetime we will cure aphasia. It’s not going to happen any time soon but I think that we are working towards understanding what happens to the brain once you’ve had brain damage. I think there are going to be some developing therapies and new approaches that are going to enable us to cure it,” Fridriksson said.

Even though the disability can’t be seen, there are therapy opportunities and ways to participate out in the community, Keator said. By making the community more aware of aphasia, the opportunities can be open to people with this language disorder.

“We are working towards those predicted measures of a cure. Telling someone after they have their stroke, ‘this is what you can expect,’ would be helpful for our stroke survivors and also family members,” said Keator.

Carl McIntyre, a stroke survivor, starred in Aphasia the Movie. He had a massive stroke in 2005 and is an advocate for the aphasia community.

At the UofSC Aphasia Lab, they focus on how the brain heals itself. The lab takes detailed images of the brain to study how the residual brain works after stroke. Photo Credit: UofSC Aphasia Lab

Photo Credit: National Aphasia Association and UofSCLab

Leigh Ann Spell, the associate director of the UofSC Aphasia Lab, is in charge of operations at the lab and recruits participants who have had a stroke to participate in research studies. Photo Credit: UofSC Aphasia Lab

Carl McIntyre wrote the word “acceptance” on a white board at the aphasia community event inside the Nickelodeon Theater. He wants stroke survivors, like himself, to be accepted in the community.