A neon sign at Menage, a large gay dance club that existed on Huger Street from 1986 to 1989 (Photo courtesy of Michael Brezicky, Historic Columbia)

“Grandma” comes everyday for happy hour, sitting with other old-timers. When he can, he stays late to watch the drag shows and the younger crowds they bring.

“Grandma” is otherwise known as Bill Skipper. The 74 year old is the president of The Capital Club and one of its founding members. He has been president since the year it opened in 1980. He likes to tell younger people about The Capital Club’s early days, a very different — and fraught — time to be in a gay bar in South Carolina.

“The kids now, I love the freedom they feel. I love it,” he said. “We’d have loved to have had that (freedom), but we all drink from wells we didn’t dig.”

The Capital Club, or simply “Capital,” as patrons call it, is the oldest operating gay bar in Columbia, and according to its website, in the Southeast. Just around the corner is PT’s 1109, the city’s other gay bar, which opened in 2000.

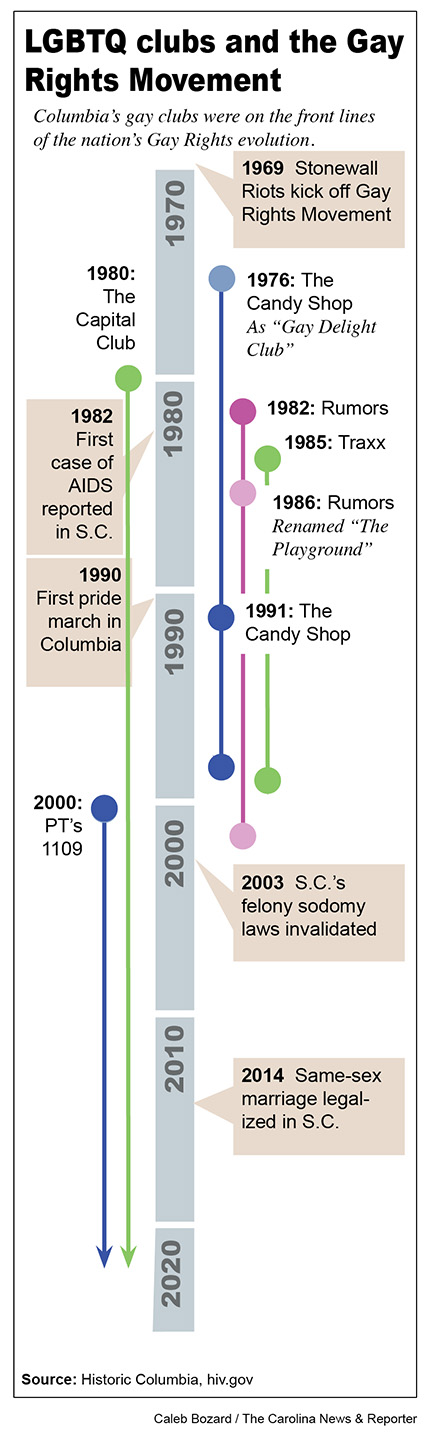

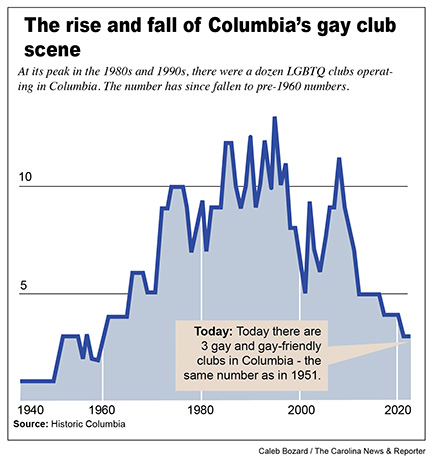

Through discussions with bar owners and patrons and analyzing records from Historic Columbia, The Carolina News and Reporter uncovered a strange statistic: Columbia, in 2022, has only those two gay bars, the lowest number in the city since 1960. The number peaked in the mid-80s through mid-90s, when 13 different such clubs spotted the city.

Skipper is one of the few who remember the era when the city’s multiple clubs attracted patrons from Charleston, Greenville, Charlotte and Atlanta.

The clubs served as sanctuaries for LGBTQ people at a time when the state still had felony sodomy laws and legal same-sex marriage was more than three decades away.

STUDIO 54 IN THE PALMETTO STATE

“People used to call Rumors ‘the closest thing a South Carolinian could see to Studio 54,’” Joseph Berliner said, referring to the famous NYC dance club. “Which is a great compliment.”

Opened in 1982, Rumors became Columbia’s premier dance club, said Berliner, who was the head DJ when the club first opened.

The building was large, with a dance floor that could hold 2,000 people. Above the dancing was Berliner in his DJ booth, who prided himself on playing the newest underground dance music before it hit the radio.

The club also featured live entertainment. The club passed on a chance to book Madonna in the early ‘80s before her first album came out because she didn’t have enough material for a full set. Once a pair of backup singers played an unreleased song they had recorded two weeks before – the duo later named themselves The Weather Girls. The new song? “It’s Raining Men.”

Like a lot of gay bars at the time, Rumors started as a private club with a guarded list of members. Private membership clubs helped protect patrons from being outed, which could cause them to lose their jobs.

But members brought their friends, and eventually those friends started bringing straight people.

“I didn’t change my musical formula,” Berliner said. “I was still playing what was typically called ‘gay music.’ And people loved it… I think that in a nutshell explains why it succeeded so well. It was different.”

A sign by the door said the membership included gay, straight, Black and white, and anyone who caused trouble would be asked to leave. On the dance floor, you would see Black drag queens dancing with businessmen, he said.

But Rumors was an outlier in that regard. Even though Columbia’s LGBTQ clubs and bars were considered safe places for members of the community, they also were usually separated by gender, sexuality and race.

A DIVISION OF THE RAINBOW — GAY CLUBS SELF-SEGREGATE

On Two Notch Road, The Candy Shop was known as Columbia’s only Black gay bar. By contrast, of the Capital Club’s 100 founding members, just one was Black, Skipper said.

The club opened in 1976 under a different name and took on The Candy Shop name in 1991.

Like Rumors, The Candy Shop was a staple of Columbia’s drag scene. It was there that a teenage Dorae Saunders saw her first drag show.

Saunders is now a nationally renowned drag performer, impersonator and MC. She competed on the third season of TV’s America’s Got Talent. The Candy Shop was where she got her start.

If Rumors was Columbia’s Studio 54, The Candy Shop was Columbia’s Apollo Theater, Saunders said, referring to the famous venue in Harlem where many Black performers got start.

“That was the only Black gay club for miles around,” she said. “There was nowhere else to come to, and it was where everybody came. You had gays there, straights there, you had everybody at The Candy Shop.”

The Candy Shop was a place where Black LGBTQ people could find support in a close-knit community, including for those who had been cast out by their families, she said.

It was also a place to get away from racism at other gay clubs, including for Saunders, a Black trans woman.

“Imagine walking into a bar that’s predominantly all white and you’re stared at, even though you practice the same sexuality. But the color of your skin, even there, dictates how people are going to treat you,” she said. “So we needed a safe space just for us.”

The clubs were also separated by gender. It was rare to see a man at Traxx, a lesbian bar on Lincoln Street that opened in 1985, patron Tammy Lane said.

Lane remembers Traxx as a rarity even among the few gay bars in town, being targeted towards women. She recalls the place being a small, shack-like building, with a bar, deck, dance floor, “the tiniest restroom you could ever imagine,” and the pool table room, where she spent most of her time.

“It might have been a little rough around the edges, but it was a safe place to have a glass of wine, play some pool and hold hands with your girlfriend,” Lane said.

Even today, lesbian bars are less common than male gay bars. In May 2020, NBC News reported that there were only 16 lesbian bars nationwide and many at the time were in danger of closing due to the pandemic.

If The Candy Shop was mainly for Black patrons, Traxx for women patrons, and Rumors for the young dance crowd, then The Capital Club was the place for older – mostly white – men.

The members-only club, dubbed a cigar bar, played classical, opera and Broadway show recordings on vinyl. It had no dance floor or stage; rather it boasted heavy, dark, English-pub style furniture. Collared shirts were required. Shorts were only permissible in the summer. Drag was not allowed.

Judges, politicians and other high profile members of the community would come in secret. Many of them were straight with gay friends, but some were closeted, Skipper, the president, said.

Even with an older demographic, the bar was a safe place where partners could hold hands and not be in danger, he said.

“That sounds strange now in 2022, but there was a time you didn’t want to do that,” he said. “Not in Columbia.”

KNOWING WHERE TO TURN

Traxx was hidden on a small gravel road off Blossom Street near the railroad tracks, Lane said, near where the University of South Carolina’s Greek Village now stands.

There were no streetlights or signs on the building. You had to know someone who knew how to get there.

“Part of that was for safety,” she said. “You didn’t really want everybody to know where you were or what you were.”

But threats of harassment remained at all the clubs.

“We all knew where the nearest car wash was because it was not uncommon to go out and find your car egged,” Skipper said.

Capital’s windows were boarded up when the club first opened, Skipper said. Before he came to Columbia, someone shot through the windows of a gay bar in Wilmington, N.C., hitting his best friend beside him. He also said he once had a knife held to his throat in the parking lot.

The wooden boards on Capital’s windows were replaced in the early ’90s with dark tint. The bar’s windows are still tinted today.

“Things have not always been the way they are now,” he said. “It was a very hard time. It upsets me sometimes when I talk about it now, but it was very dangerous.”

At The Candy Shop, people would drive by yelling slurs while throwing eggs and water at people standing outside. Saunders said she and a few others once waited for hecklers to drive back around the block in their truck, then they threw beer bottles at it, shattering the back glass.

Inside the clubs, Berliner said he likes to think clubs like Rumors gave straight people a chance to be exposed to LGBTQ people and culture in a way that encouraged acceptance in the broader community.

Saunders, however, isn’t so sure.

Straight people “came (to The Candy Shop) because their friends were gay and they were just hanging out,” she said. “It wasn’t about acceptance.”

A GAY MAN’S DISEASE

In 1983, Tony Price, a regular patron of the clubs and a gay rights activist on USC’s campus, was in a play at the school’s Longstreet Theater. He remembers thinking one of the cast members playing a concentration camp prisoner was perfect for the role because of how thin he looked.

A few months later, Price heard the man was in the hospital.

“I just remember saying, ‘What do you mean?’ And they said, ‘Well, we think he’s got it,’” Price said.

“It” was AIDS.

The first cases were seen in California and New York in 1981, according to hiv.gov. In 1982, South Carolina’s first case of what was dubbed the “gay cancer,” because it disproportionately affected gay men, was diagnosed in Charleston.

According to Price, the disease began to move through Columbia in 1985, the same year he took a job with the state health department to promote AIDS awareness. The city’s gay clubs soon were on the front lines of the epidemic.

He said young men who had been diagnosed with the disease would come to him in the bathrooms of gay bars crying and asking for help. He would give them his number but would rarely hear from them again.

He would hear about someone being admitted to the hospital, then hearing they had died before he got a chance to visit them.

Price’s partner of 11 years was diagnosed in 1985 and died in 1991.

“There was a lot of death at that time,” he said. “You know, I just got tired of going to funerals.”

Skipper said members of The Capital Club were going to funerals once or twice a month for a 10-year period from the early 80s to early 90s.

“There was easily 50, 60 people that died while I was holding their hand, and I watched them take their last breath,” he said.

Adding to the fear was confusion over how the disease was transmitted. Patrons in the clubs started bringing their own glasses and would ask the bartenders to sanitize chairs and spots on the bar where HIV+ people had sat, Skipper said.

And there was a fear of touching AIDS patients.

Straight people stopped coming as often, Berliner said.

And yet, the clubs survived. For some, they became more important than ever.

ACTING UP

Clubs in Columbia became refuges for HIV+ people as the epidemic continued. They held fundraisers to help patients cover the cost of treatment or funerals. AZT, the first FDA-approved drug to fight AIDS, was released in 1987. But it was expensive and caused serious side effects, Skipper said. Insurance companies often dropped patients who tested positive for HIV, making the drug even harder to get.

After the initial wave of fear and silence, national AIDS activists forced discussion of the disease – and other issues in the gay community – into the mainstream. Columbia hadn’t had a gay rights movement in the 1970s like bigger cities, so the activism that sprung from the clubs during the AIDS movement was the first time gay liberation had come to the city and state.

“It’s awful to say, but we often look for some sort of silver lining …,” Price said. “If HIV had not come along, would it have taken longer to build the coalition of LGBTQ community support?”

In 1990, the first “gay pride” march in the state was organized in Columbia. The night before the march, Skipper was at The Capital Club with Harriet Hancock, a key figure in organizing the march who also founding several local LGBTQ advocacy groups, including the Harriet Hancock Center.

Skipper said the group got a phone call from the city’s chief of police, who told them the police department had received calls that there would be snipers on the roofs of buildings on Main Street waiting for the marcher to pass by.

“(He said), ‘We can’t guarantee your safety. Are you sure you still want to march?’ And we said, ‘Hell yeah.’ And we did. We’re all looking at the buildings, wondering who was going to be picked off first.”

WHERE DID THE GAY CLUBS GO?

Snipers never attacked the pride march, and the AIDS crisis didn’t kill off gay bars, but many who are still around from that period say there was a noted change in the culture of the clubs.

“That whole mentality of, ‘Let’s go out and party every night and look good and hook up with someone different,’ that died,” Skipper said. “People were scared — scared as shit.”

Other changes came. The disco party trend of the ’70s and ’80s ended. Additionally, gay acceptance increased in the 1990s, changing the demographics of bars. Finally, the rise of the internet paralleled a drop in the number of gay-only clubs, nationally and locally.

Rumors closed in 1986. Other clubs opened in the same building — at first they remained predominantly gay clubs, Berliner said, but each new iteration of the club became more college oriented and less gay oriented. The building last housed a club in the early 2000s. It is now the downtown campus of Midtown Fellowship Church.

The Candy Shop closed in 1997. The building now serves as Benedict College’s Community Learning Center.

Traxx closed in 1999, when it was sold to a new owner, who died soon after, said the original owner, Deborah Hawkins. The building was later demolished for construction of USC’s Greek Village.

Other LGBTQ bars opened throughout the ’90s, but Historic Columbia’s records show a sharp decline in the number of gay clubs starting in the early 2000s. Ironically, the decline came as legal acceptance rose. In 2003, the state’s sodomy laws were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court, and in 2014, gay marriage in the state was legalized.

National data compiled by Greggor Mattson of Columbia University mirrors these trends. His research shows the number of LGBTQ clubs listed in travel books peaking at over 1,500 in 1987 — Columbia counted 10 clubs that year — and declining after.

Some who are still around from Columbia’s gay bar heyday think there is less demand for LGBTQ clubs because members of the community are more accepted in society.

“We have gay politicians, out gay people in banking and real estate and the medical field — everywhere,” Berliner said. “It’s no longer a thing where people feel like they have to hide or go to a club that has a backdoor because they don’t want somebody driving by to see them going in.”

Mattson also noted the rise of the internet in the late ’90s allowed people to connect online without having to go out in public.

DO WE STILL NEED GAY BARS?

Capital Club and PT’s are the only remaining dedicated gay clubs in the city. A third bar, Art Bar, which opened in 1992, is a popular “gay-friendly” club, Price said.

“Right now, I think Columbia has about as much as (it’s) going to support,” Skipper said.

Capital and PT’s survived because they evolved with the times, Skipper said.

PT’s has remodeled multiple times to keep current, said owner Tony Fusaro.

Capital lost its dress code and diversified its membership. New owners began hosting drag shows in 2014, which seem to be a popular attraction for straight crowds, Skipper said.

“Straight people might not want to go to a gay bar, but when you put it in their element, they’ll appreciate a show,” Saunders said.

The straight crowds are good for business, said Fusaro.

“I don’t think there’s anything as exclusive as a gay bar anymore,” he said.

Skipper agrees, adding that Capital can now take in on a single night what it used to make in a week.

The money is good, but the clubs remain important because there are still many places in the state, in the south and in the country where you can be the victim of violence, he said. And that progress can always be rolled back.

“I’m probably overly cautious, maybe because I’ve been shot at,” he said. “Maybe I’m a little more cynical, but I’m also not a fool.”

Skipper said despite the drop in clubs locally and nationally, they will always be necessary “because everyone is not comfortable sitting in a straight bar, holding their boyfriend’s hand or their girlfriend’s hand. Everyone who’s trans does not feel comfortable going into the men’s bathroom. In some places, you don’t have a choice.”

Despite the changes to Capital since 1980, the original bar is still in its original spot on the floor. The remaining original members still come for happy hour, where the music is low and the crowds sparse.

“Every once and a while, when there’s an empty chair, I’ll see somebody I knew back in the early 80s,” he said. “I visualize where they sat. It’s a feeling, or sometimes, I can feel their presence.”

The front entrance to The Capital Club, the longest continuously operating gay bar in Columbia (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

The only signage at The Capital Club since the day it opened in 1980 has been a small plaque by the front door, reading “members only” – the discretion was to keep those inside safe (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

Bill Skipper, 74, has served as president at the Capital Club since its opening year in 1980. He said he sometimes sits at the bar in the quieter hours before the crowds come and remembers those who used to sit with him all those years ago. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

The main entrance of PT’s 1109, one of Columbia’s two remaining prominent gay bars (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

PT’s 1109, one of Columbia’s few remaining gay bars, features male dancers and popular drag shows. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

The building that now serves as Midtown Fellowship Church’s downtown location once housed several gay bars, including Rumors, which was once called Columbia’s Studio 54. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

The building that formerly housed The Candy Shop, Columbia’s only Black LGBT bar, has since been renovated and now serves as Benedict College’s Community Learning Center. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)

The former location of Traxx, before the building was demolished. The site is still vacant, but a new student housing complex is being constructed in the adjacent lot. (Photo by Caleb Bozard)